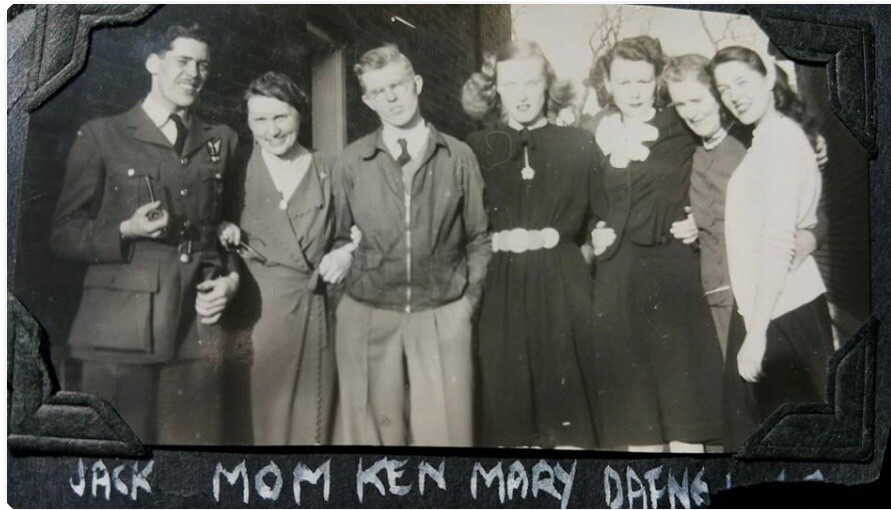

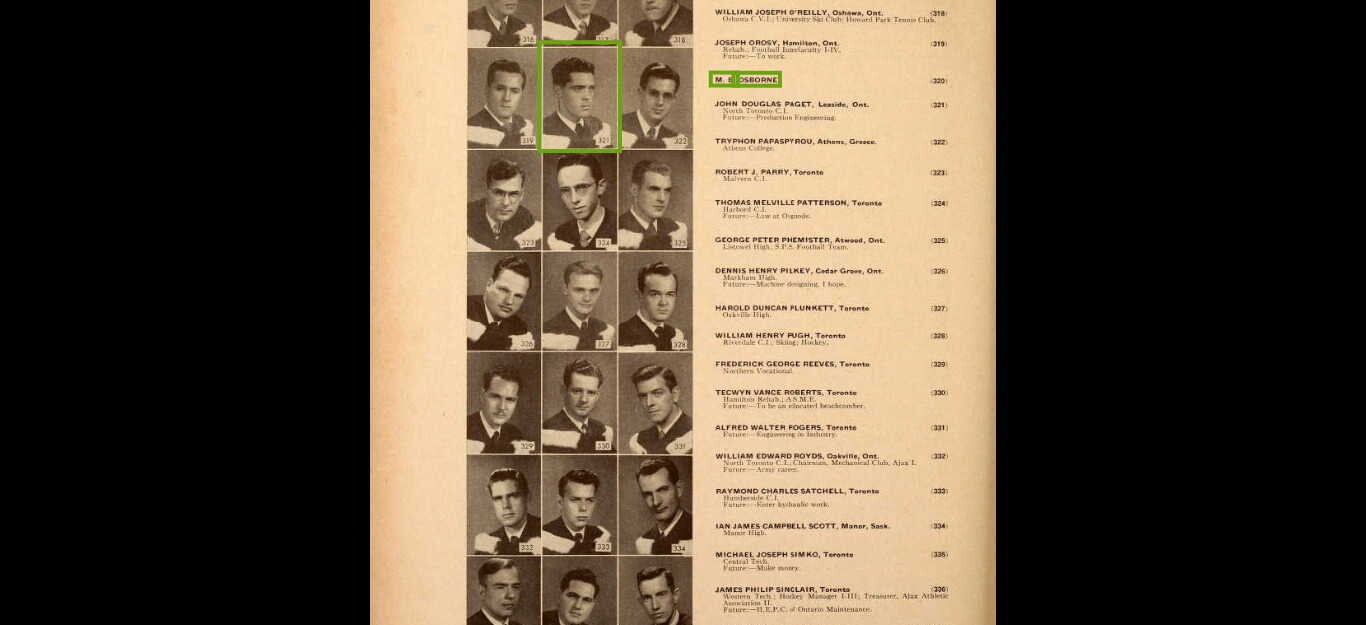

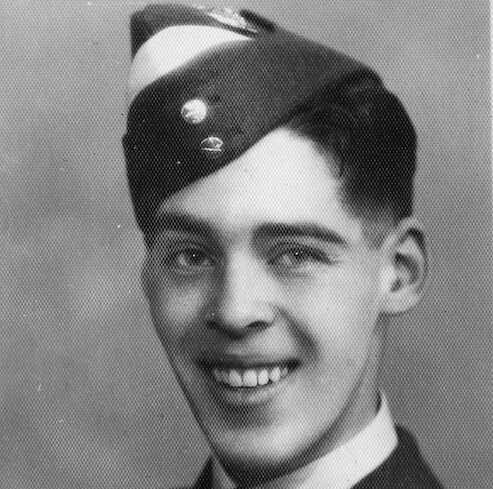

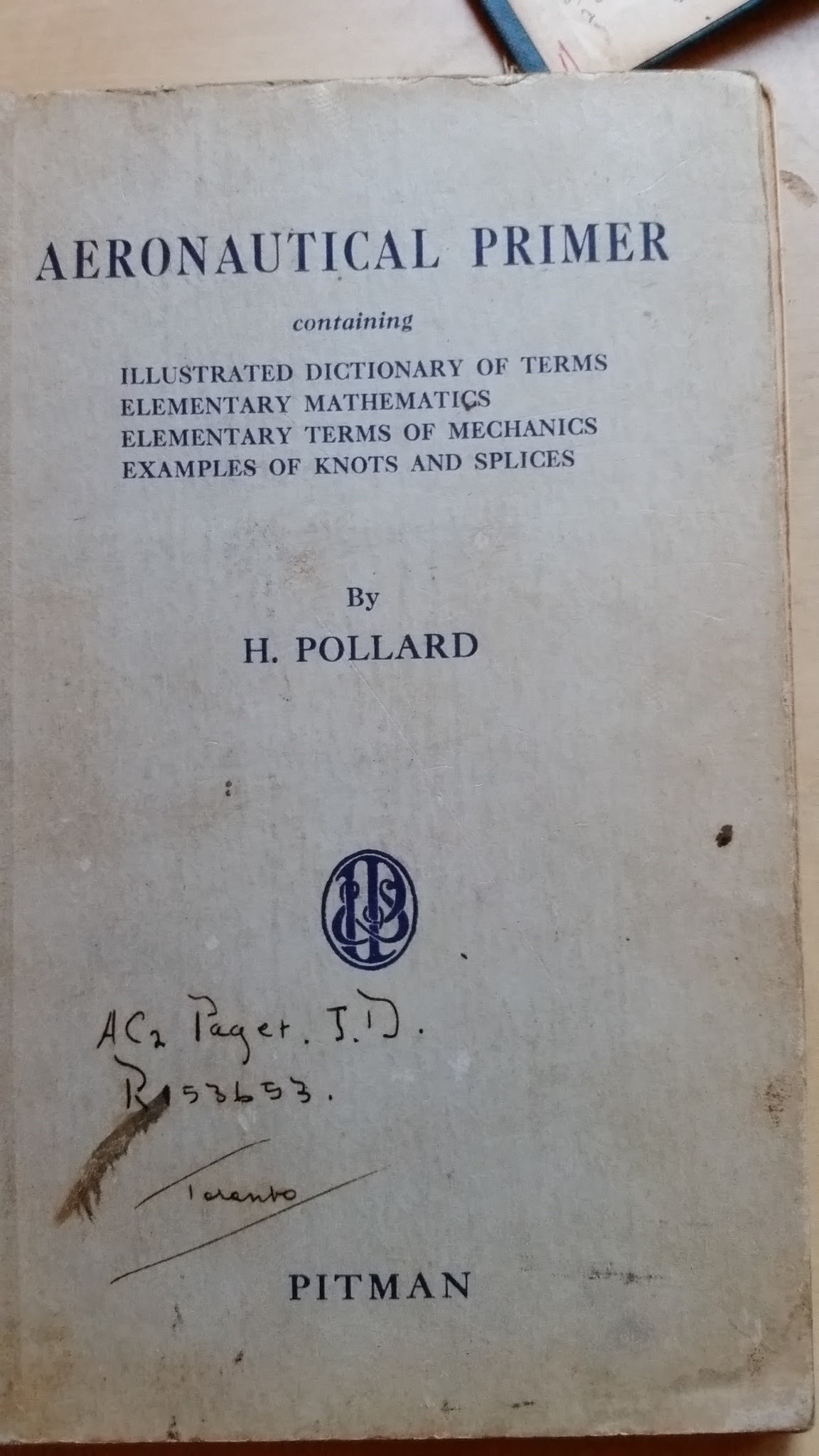

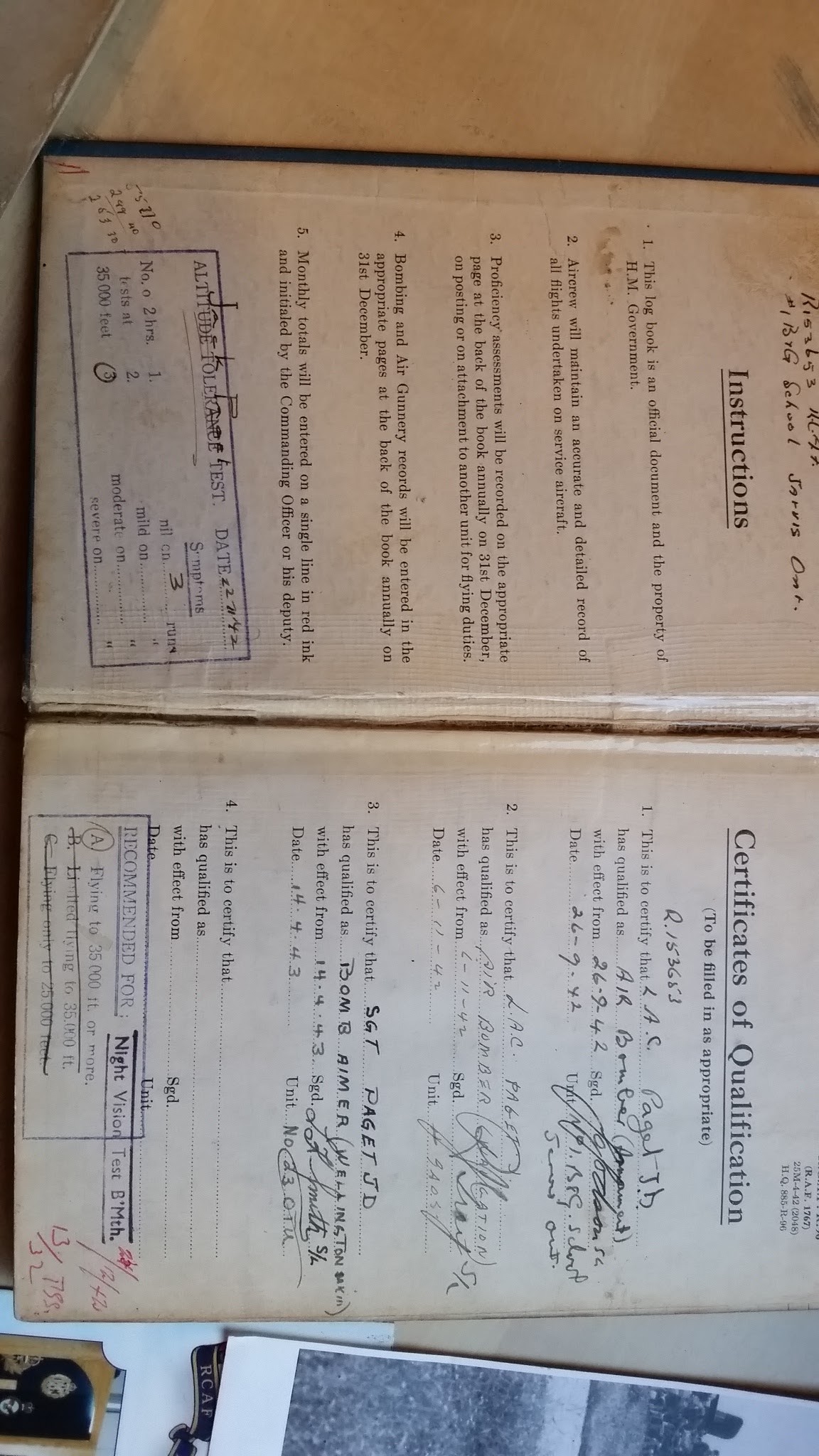

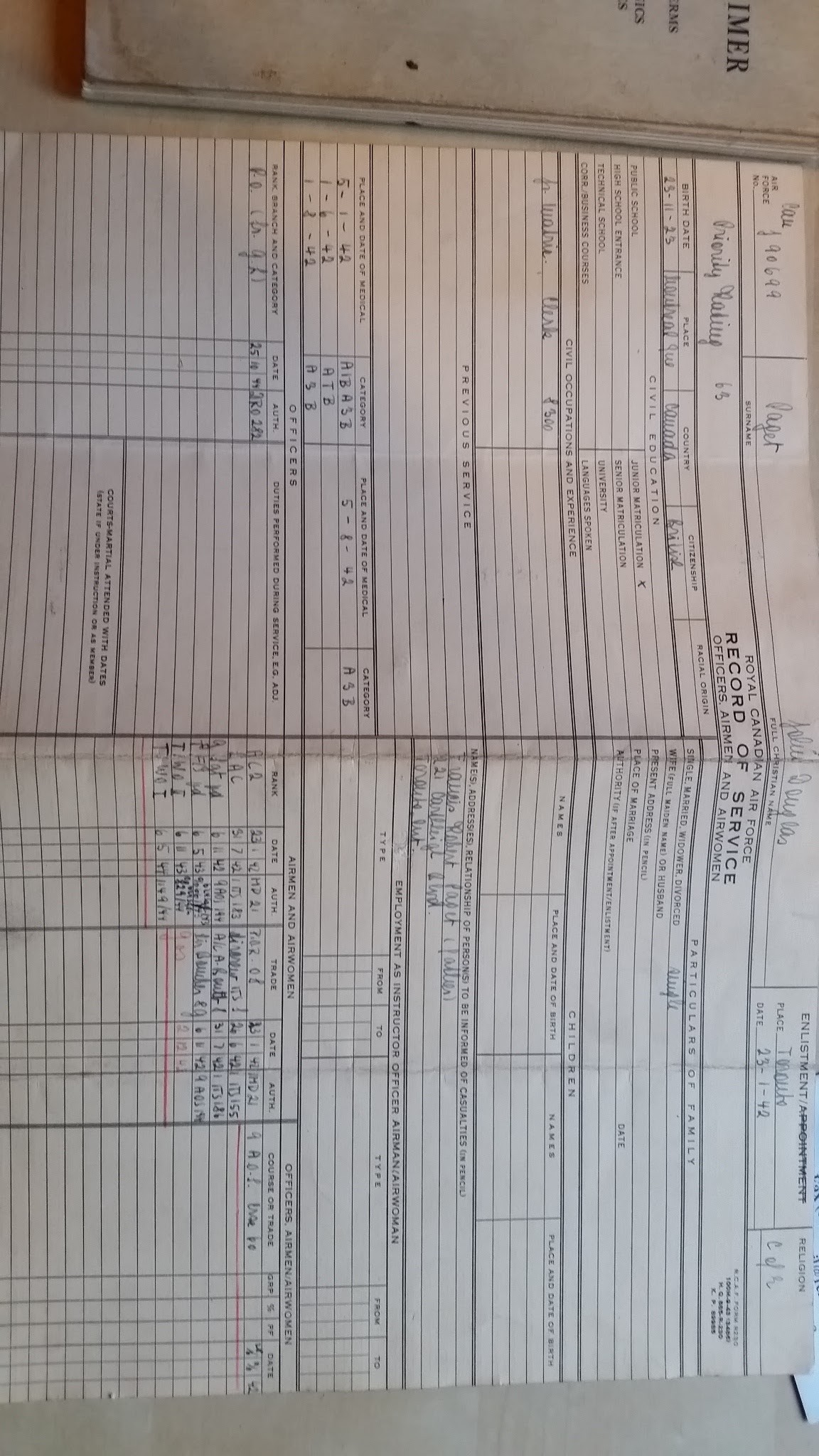

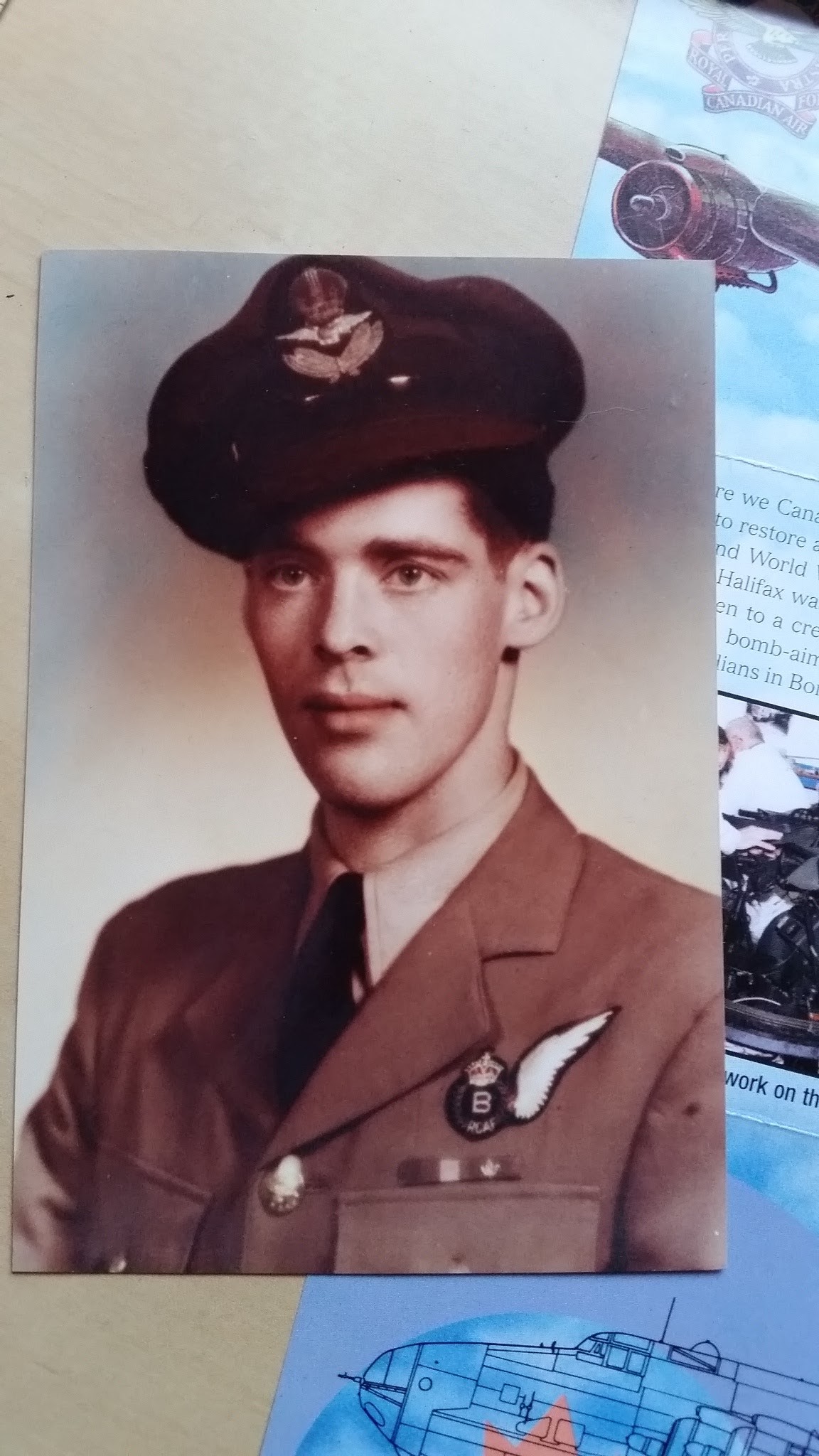

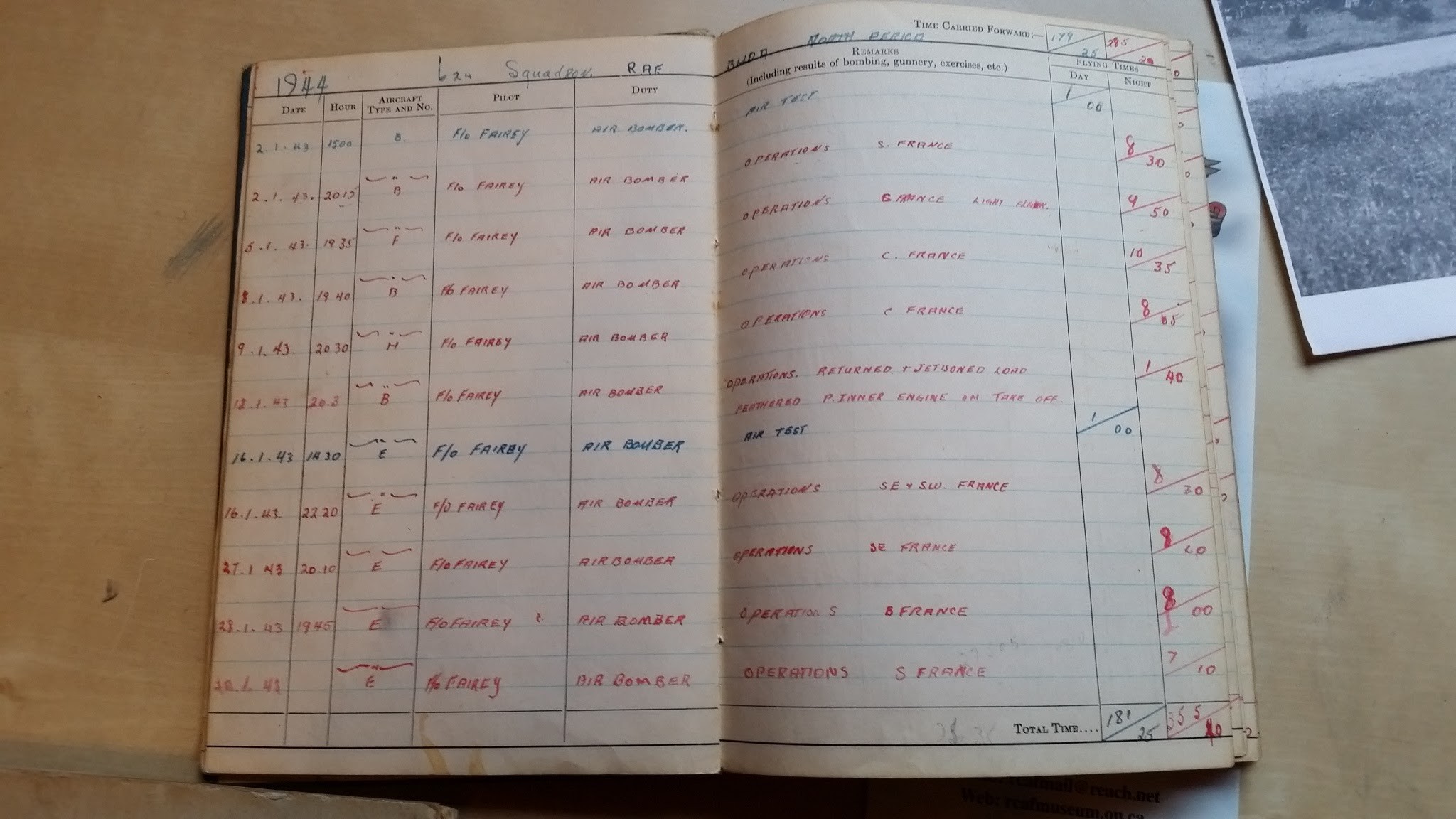

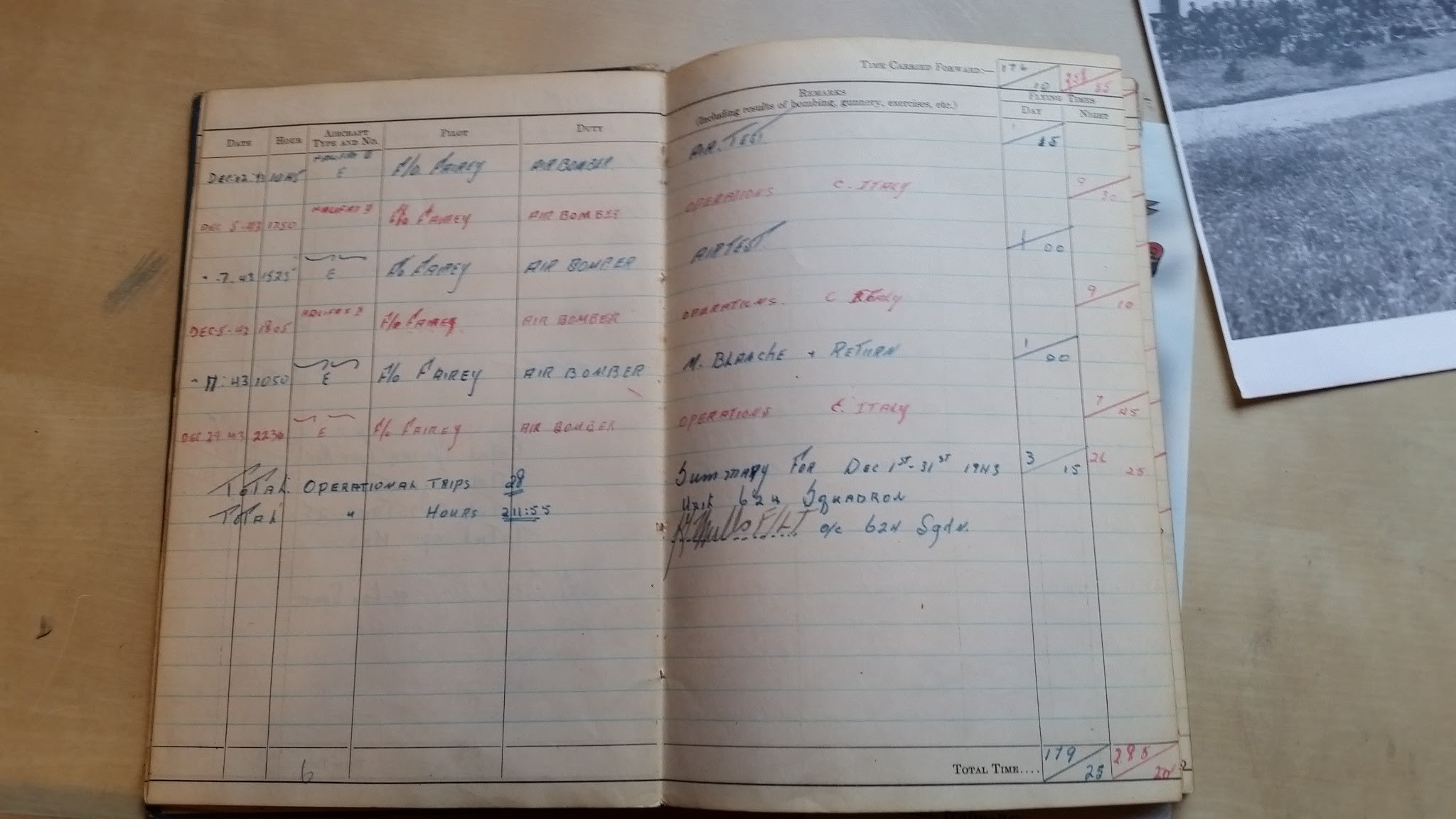

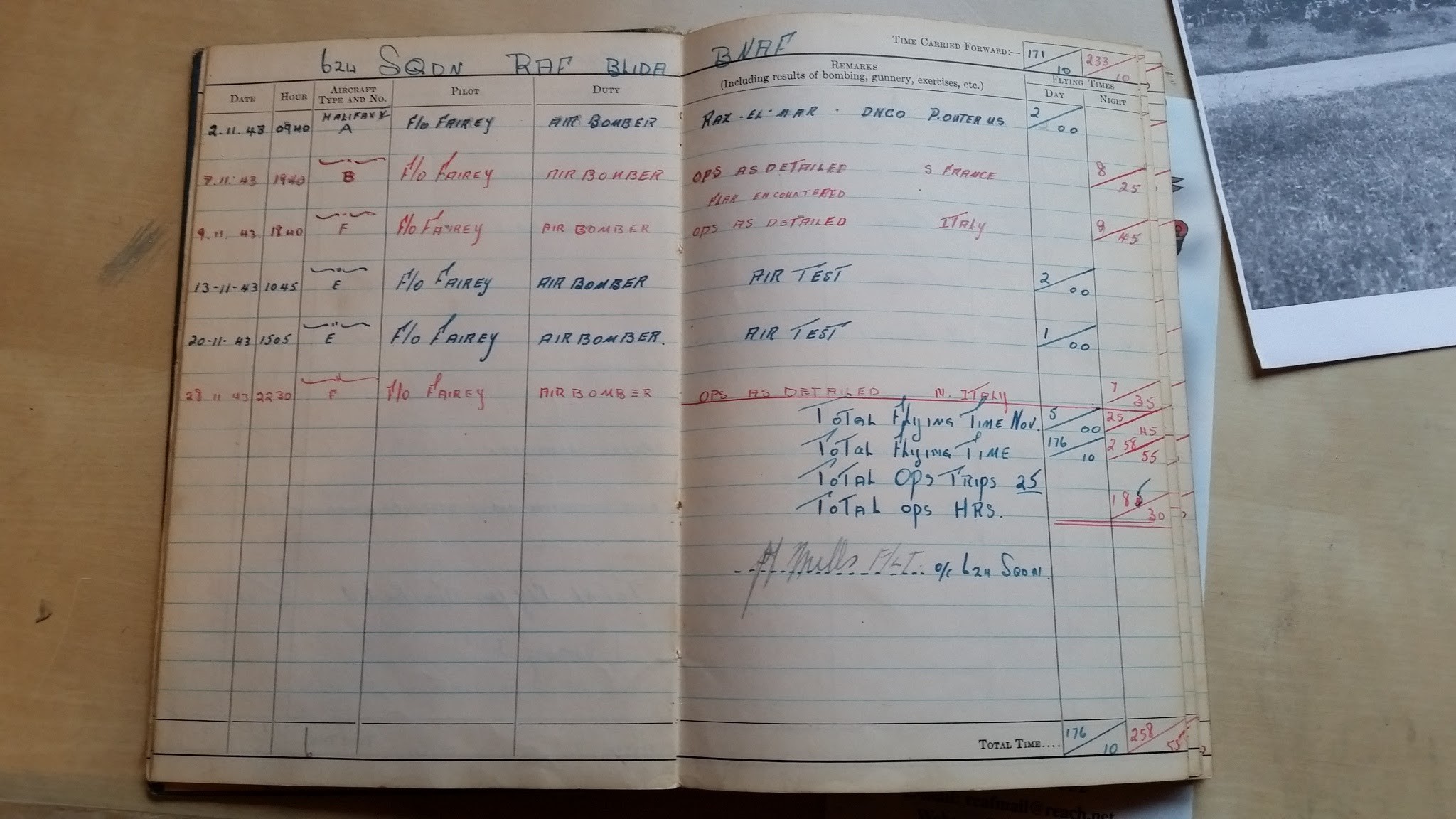

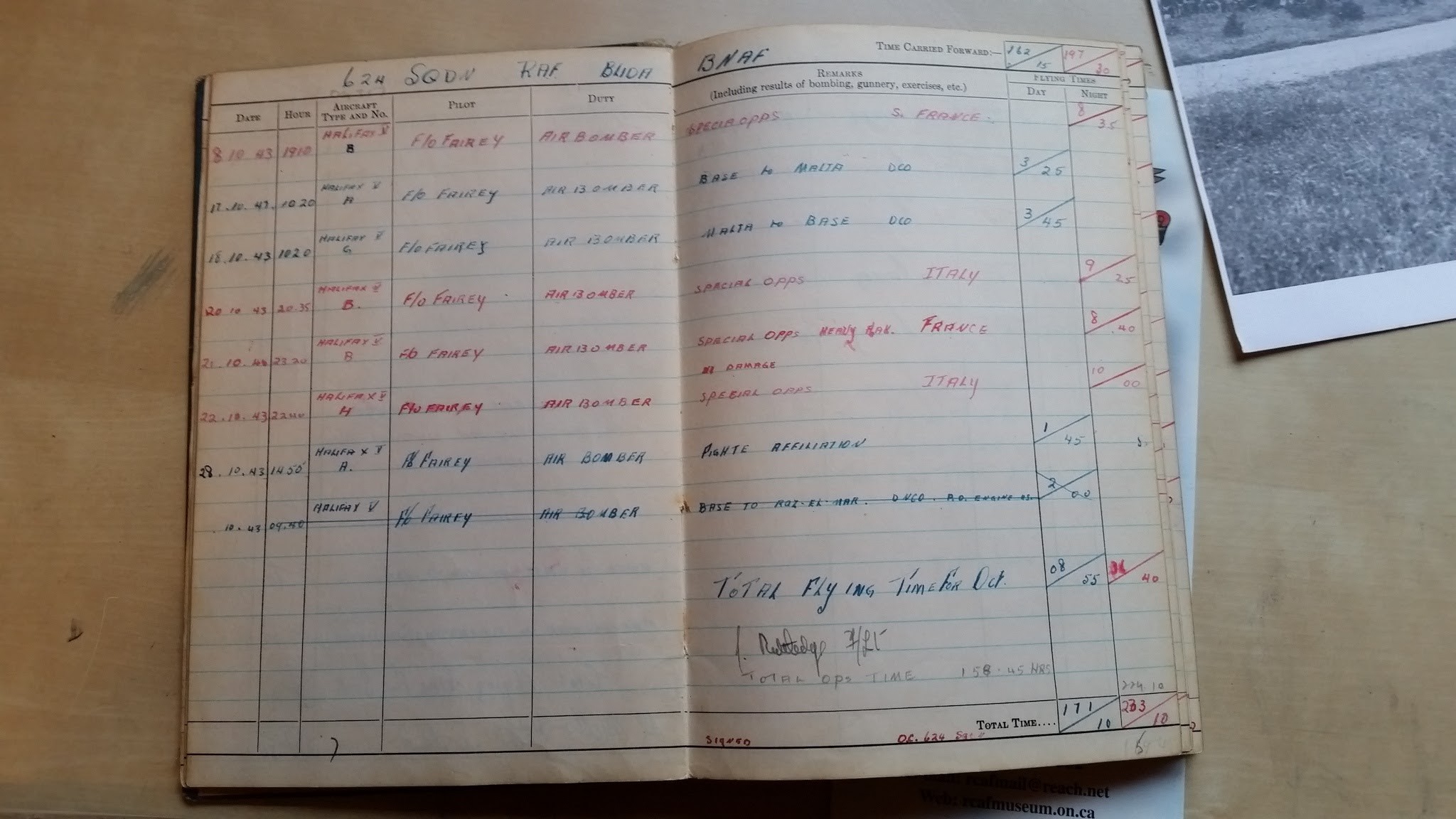

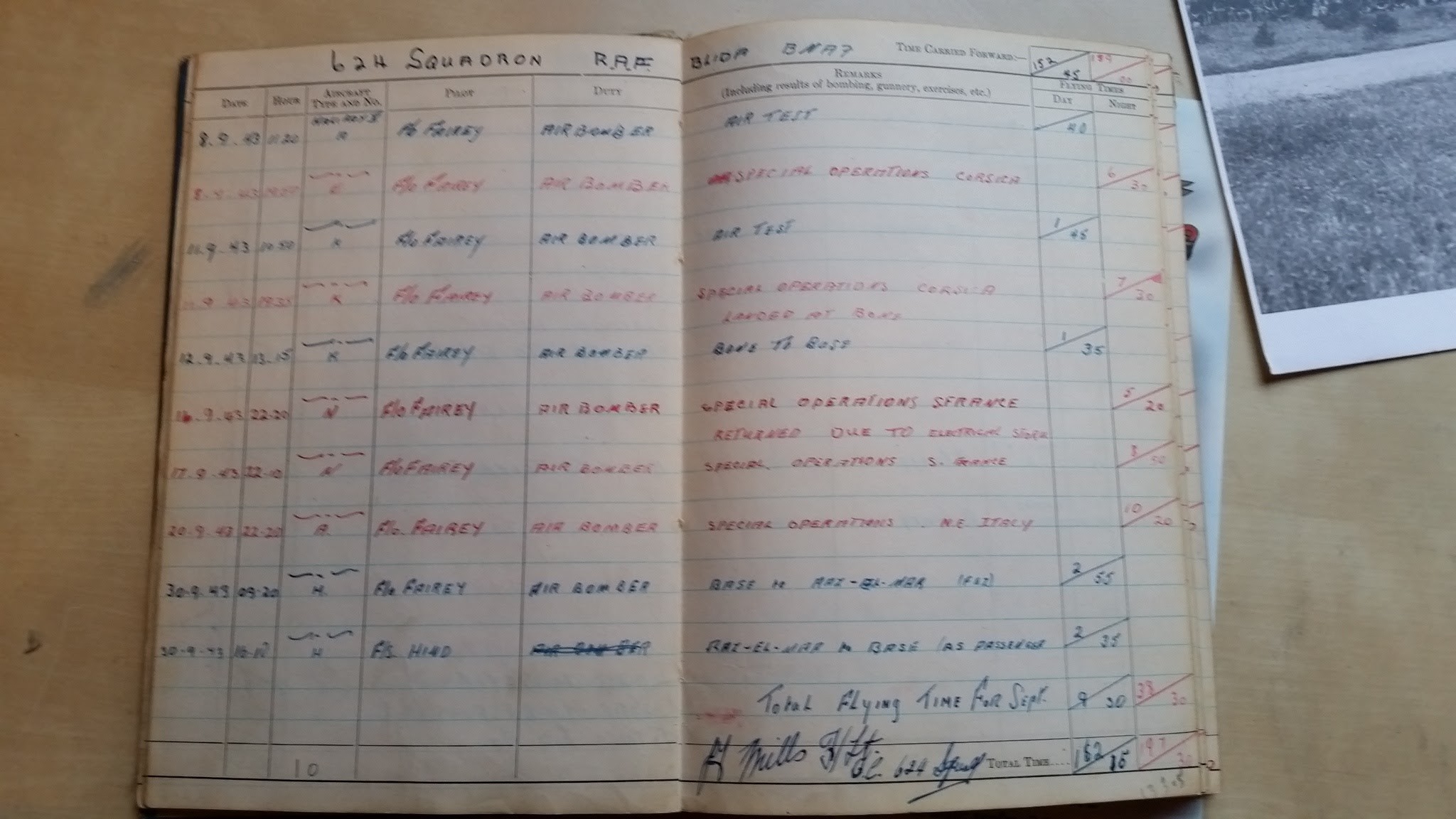

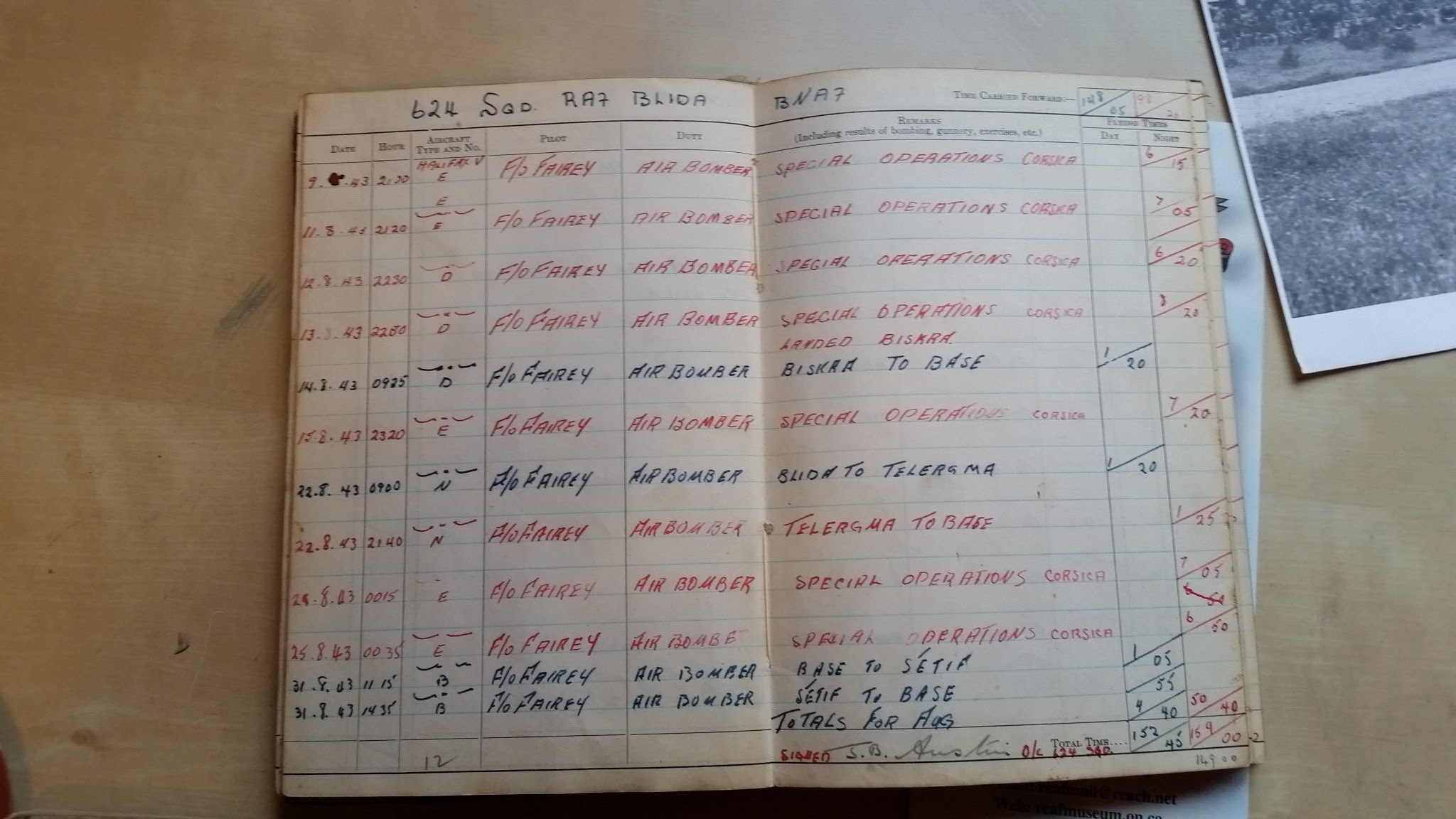

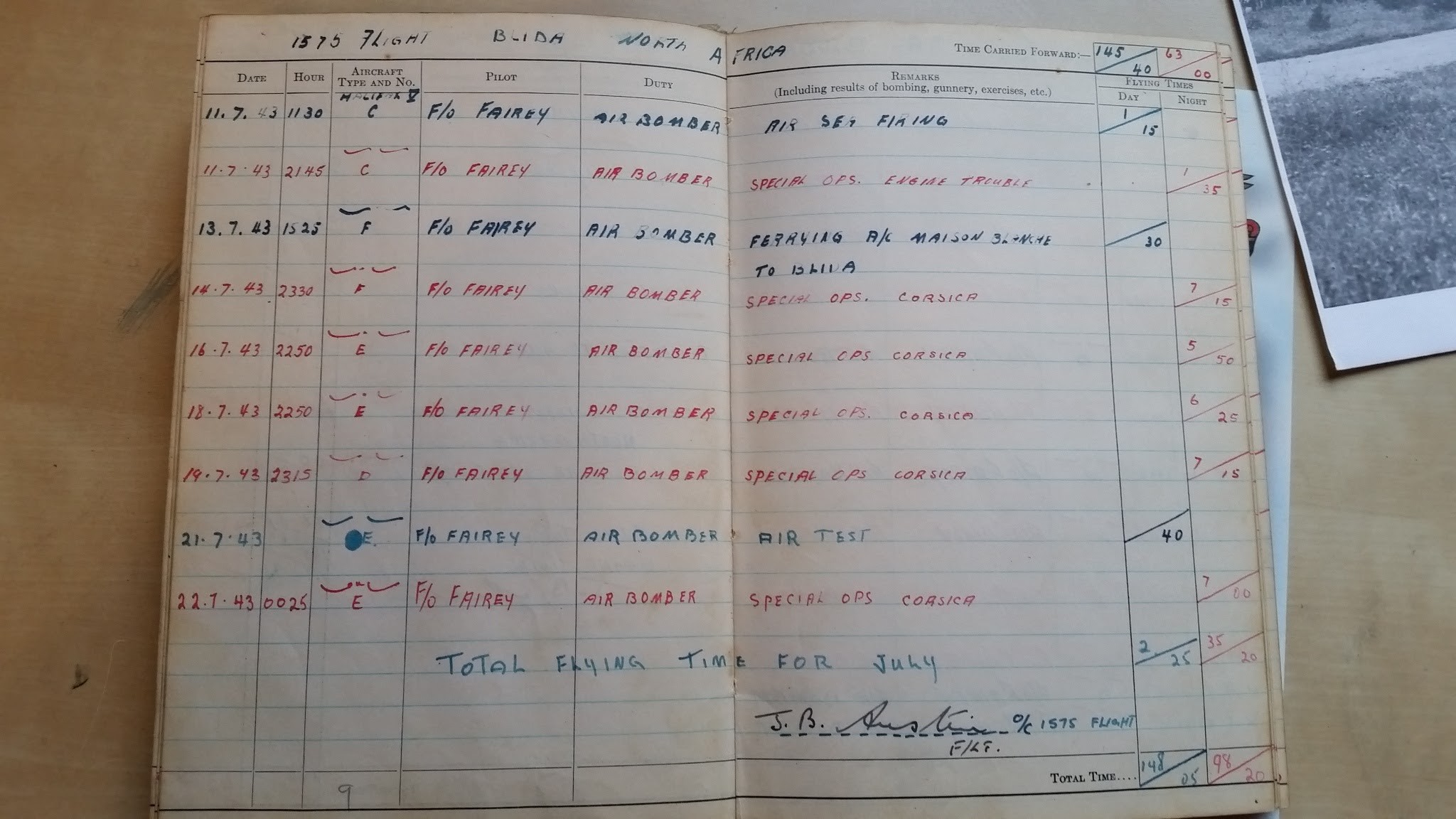

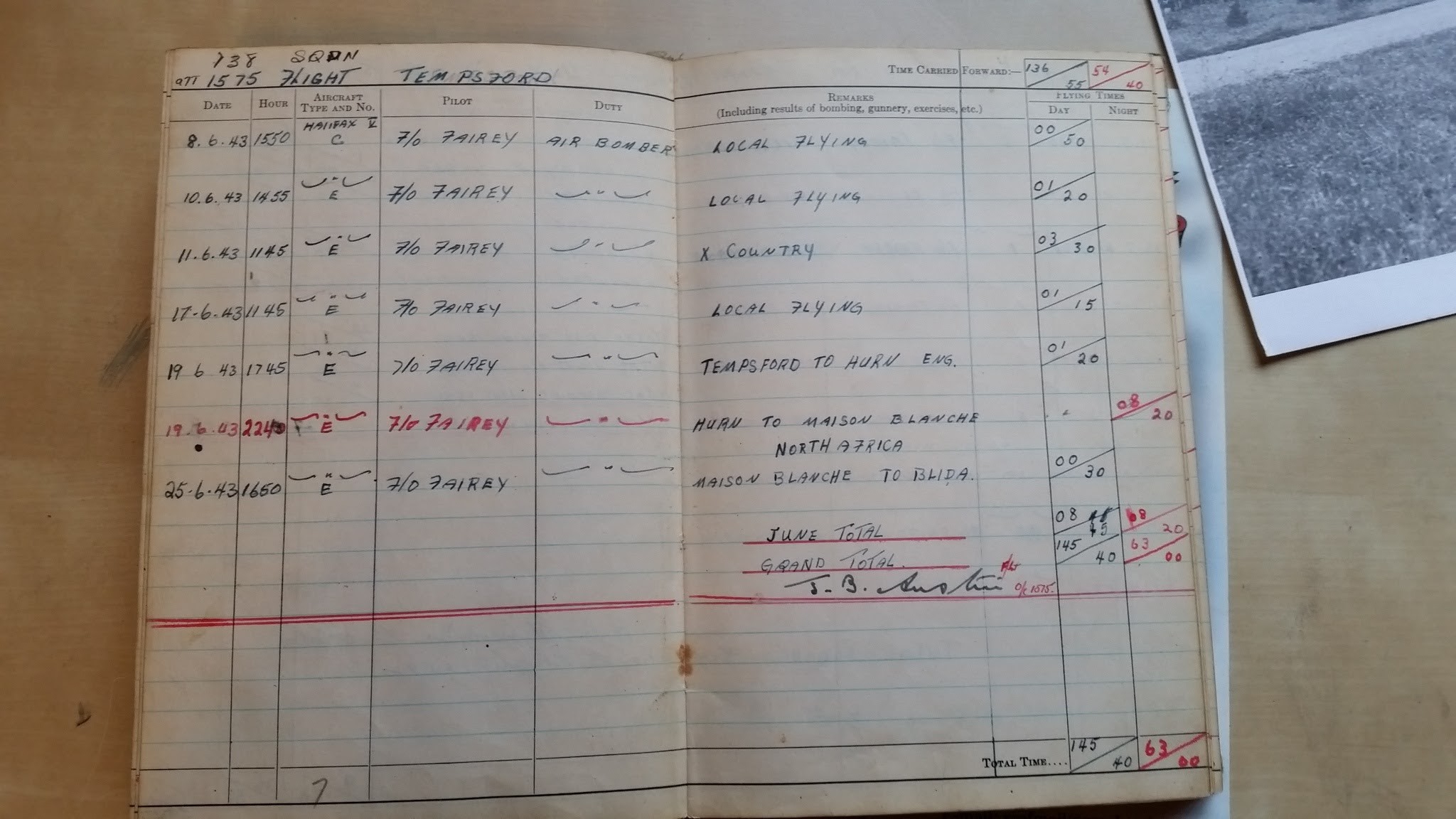

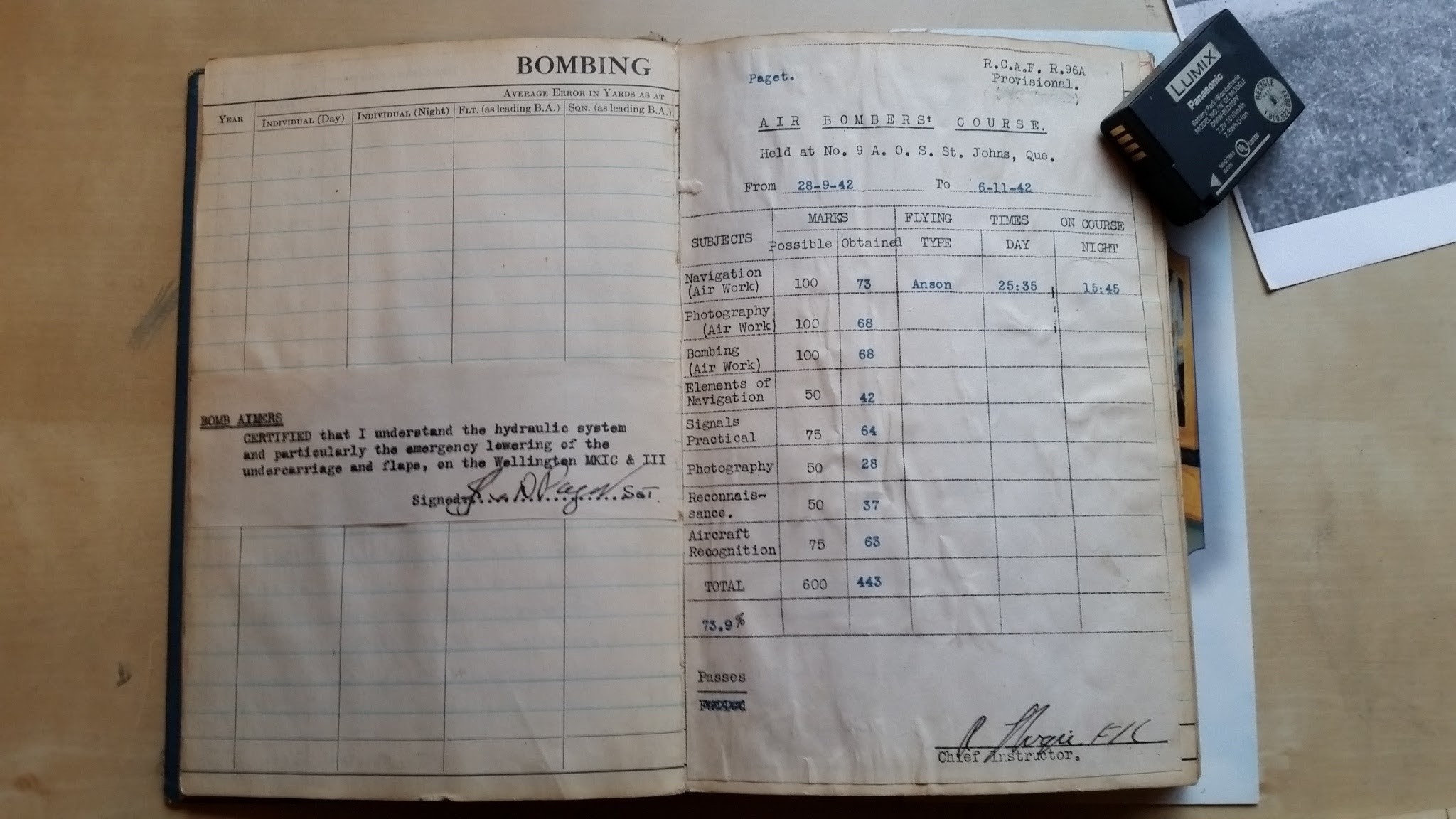

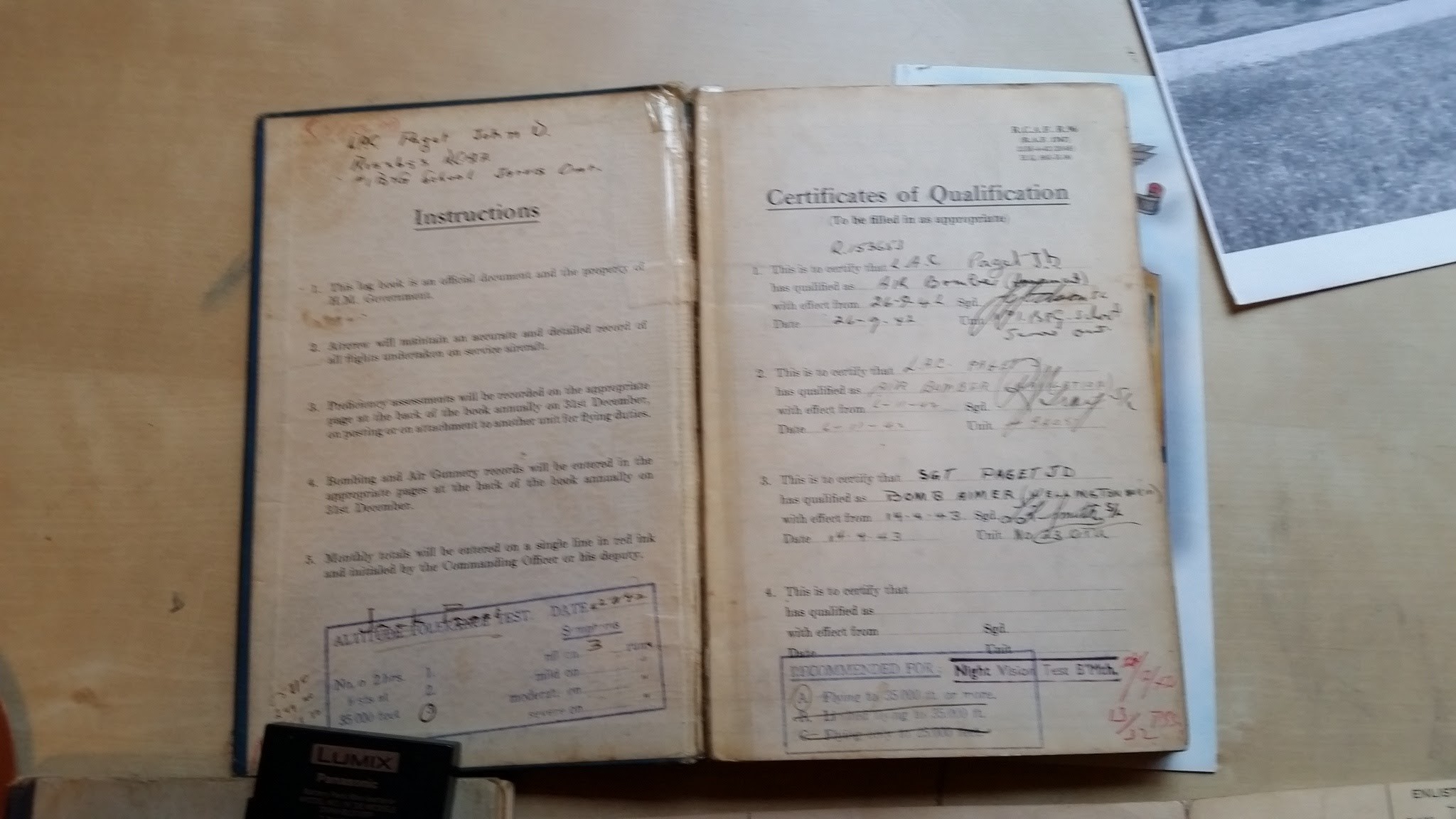

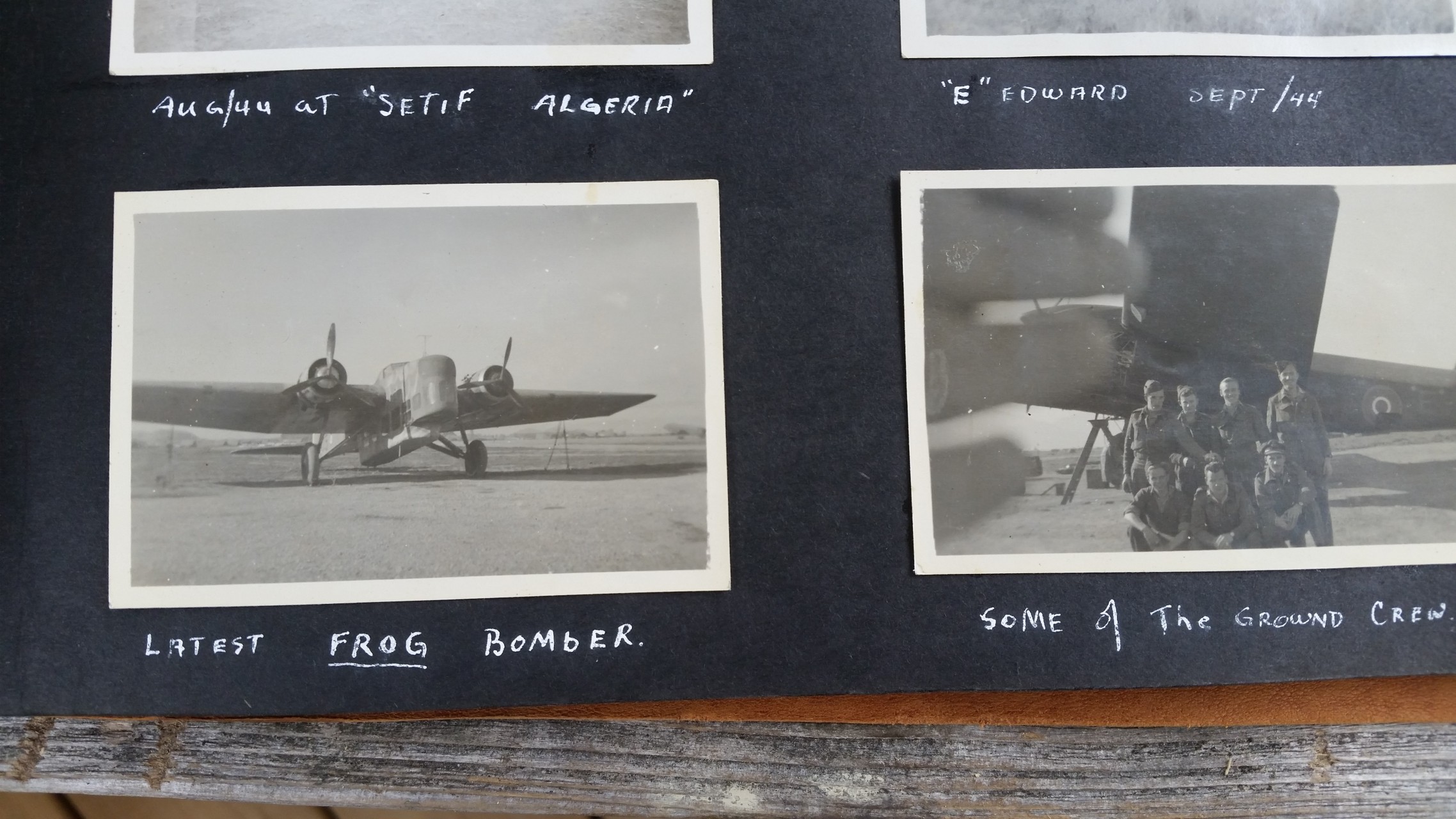

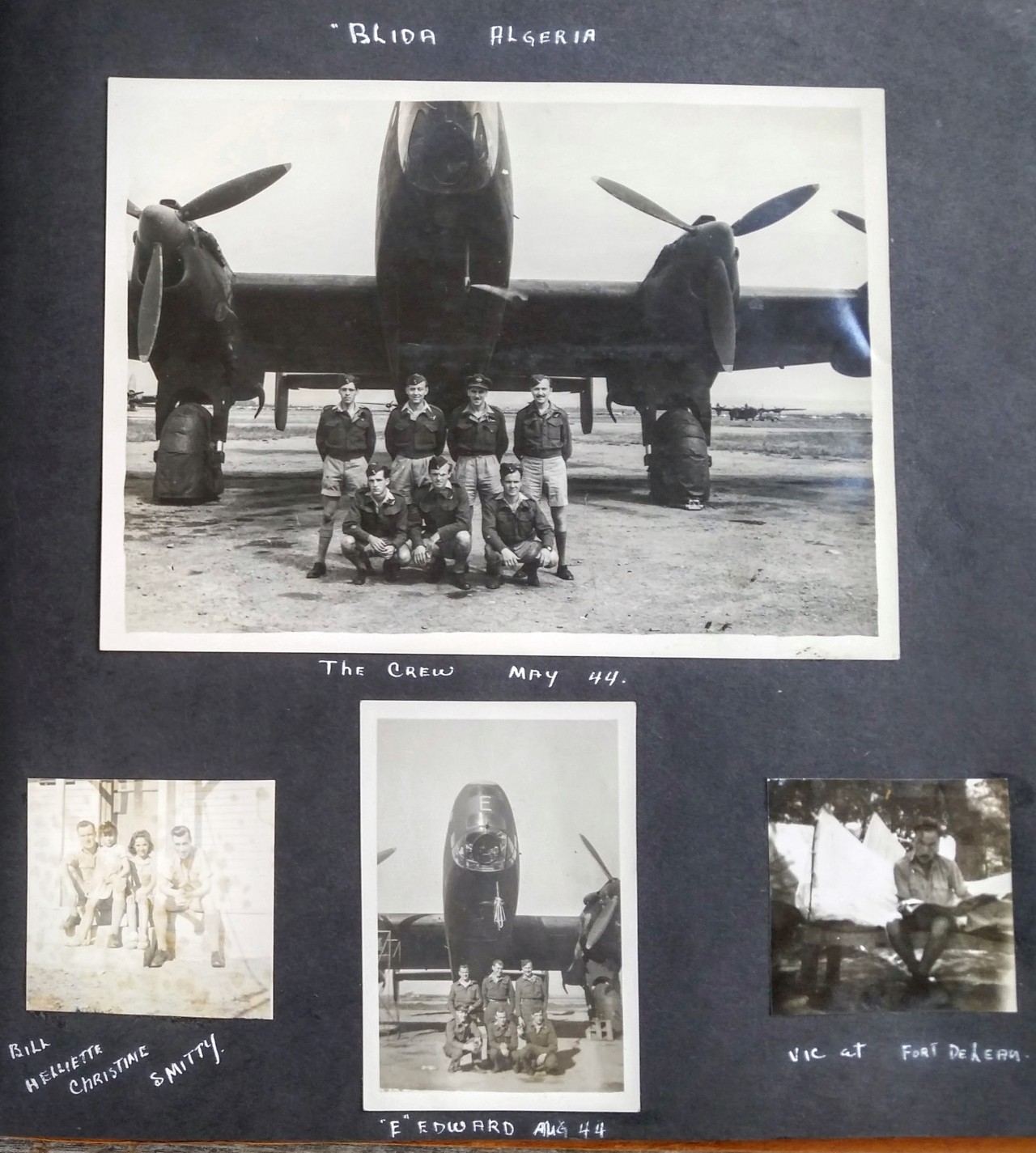

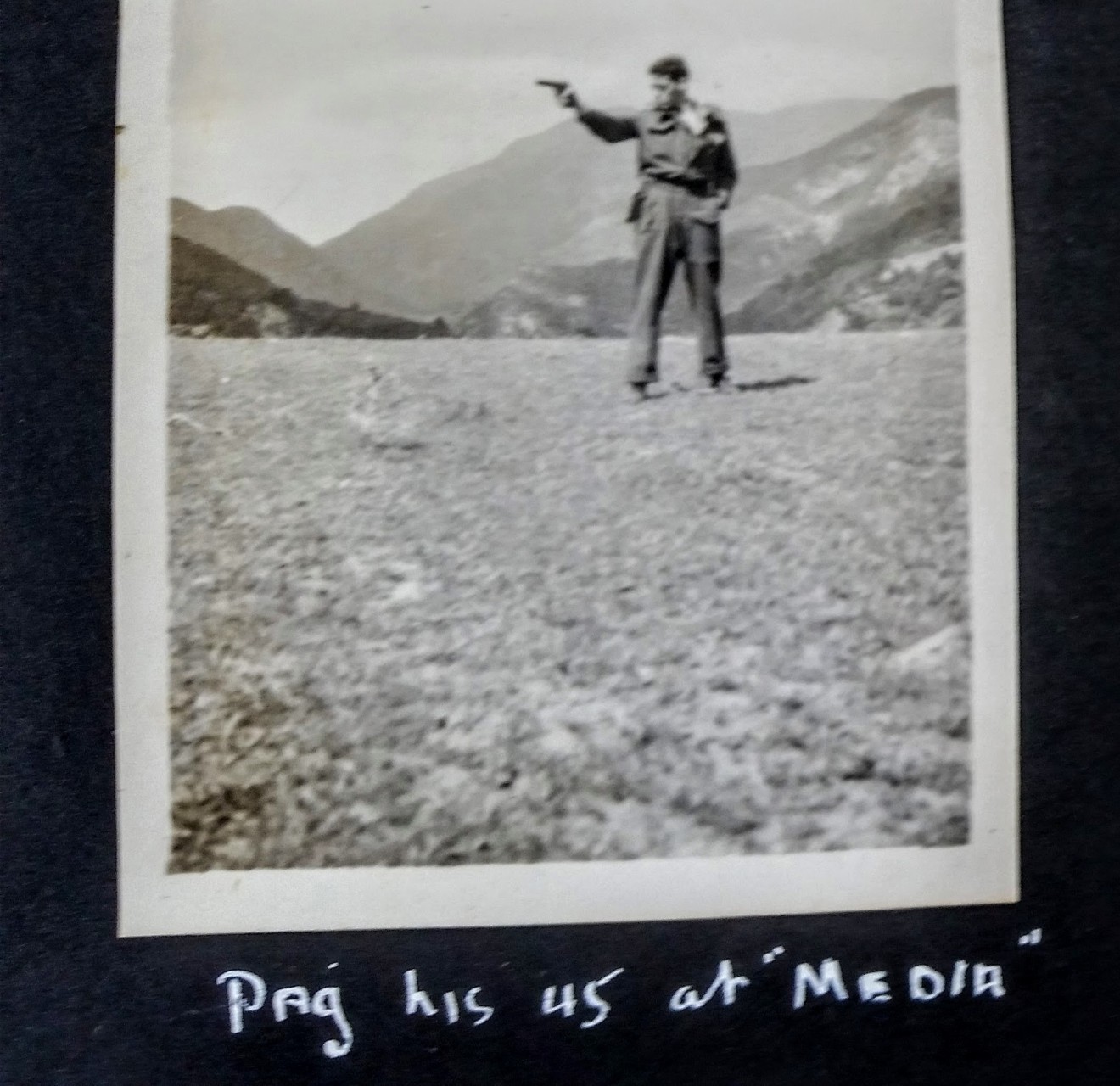

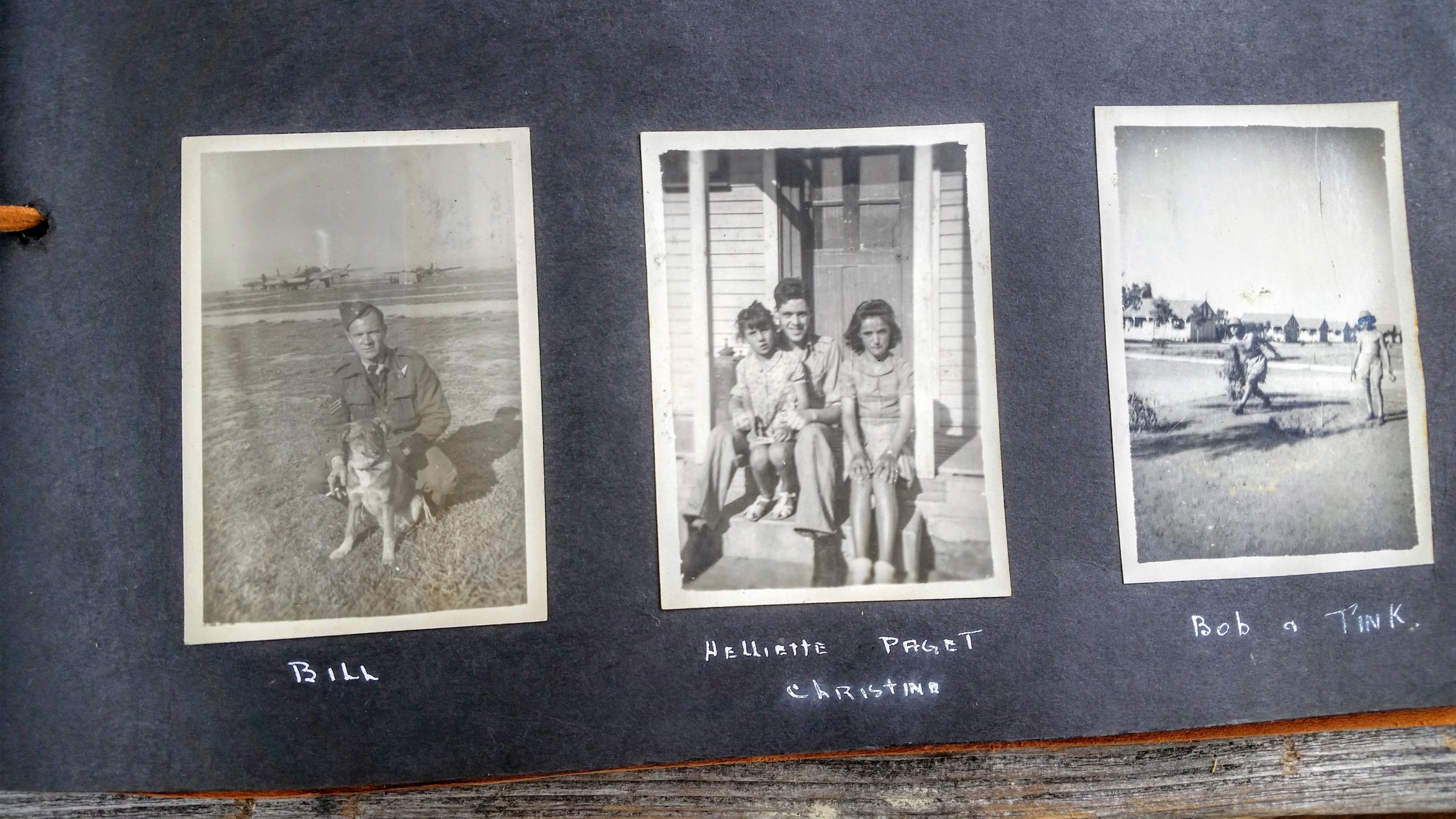

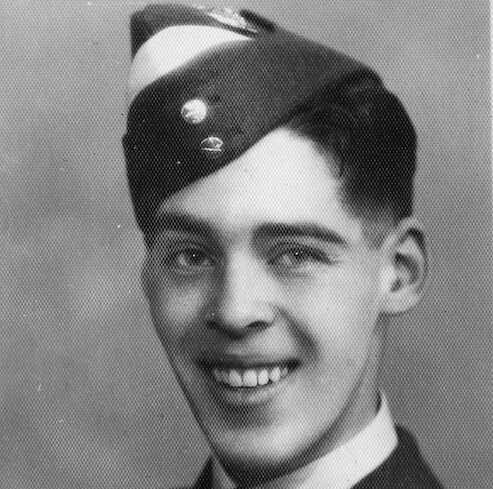

Flight Sergeant John Douglas Paget

Royal Canadian Air Force Bomber Crew • 624 Squadron RAF

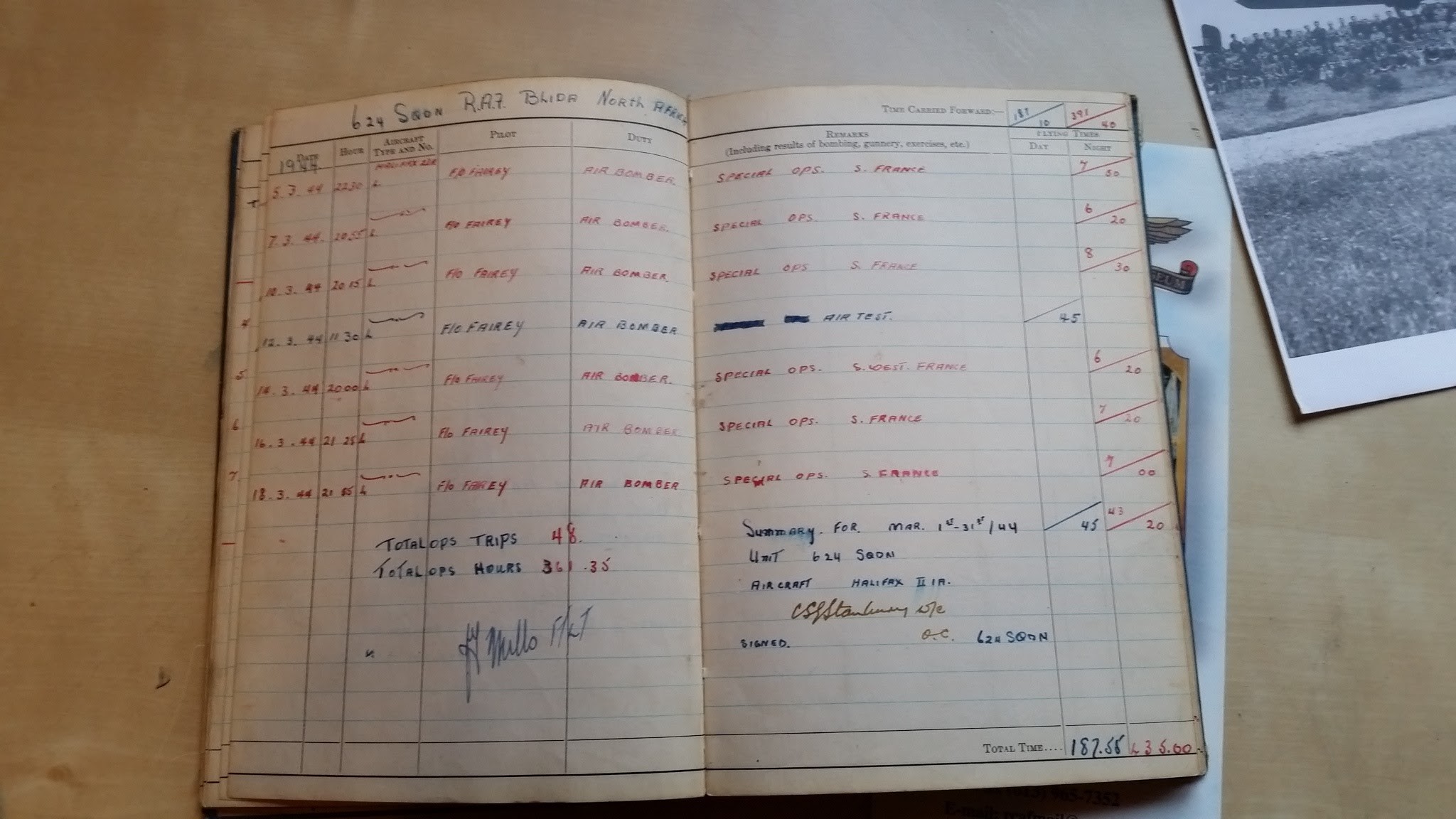

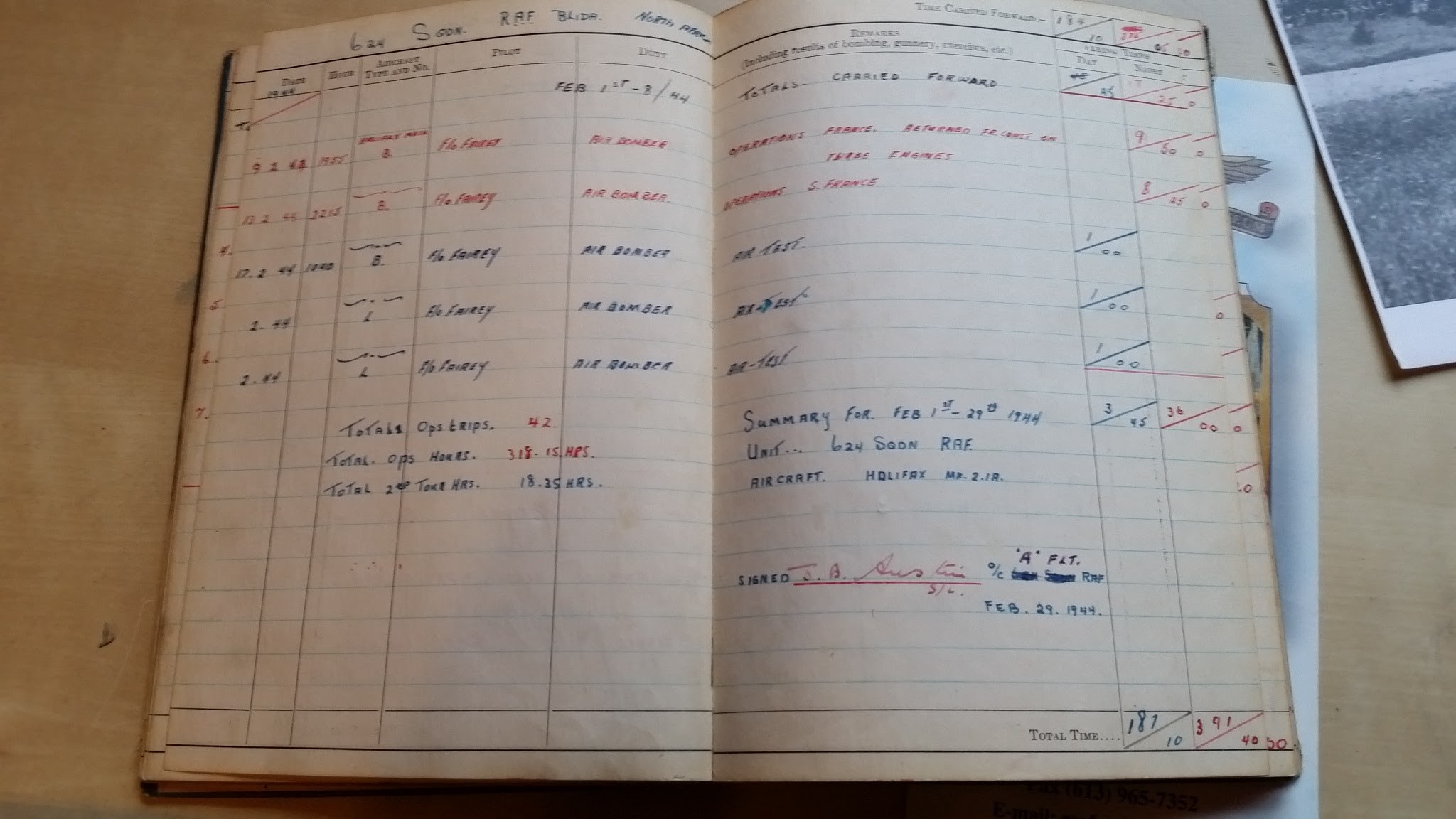

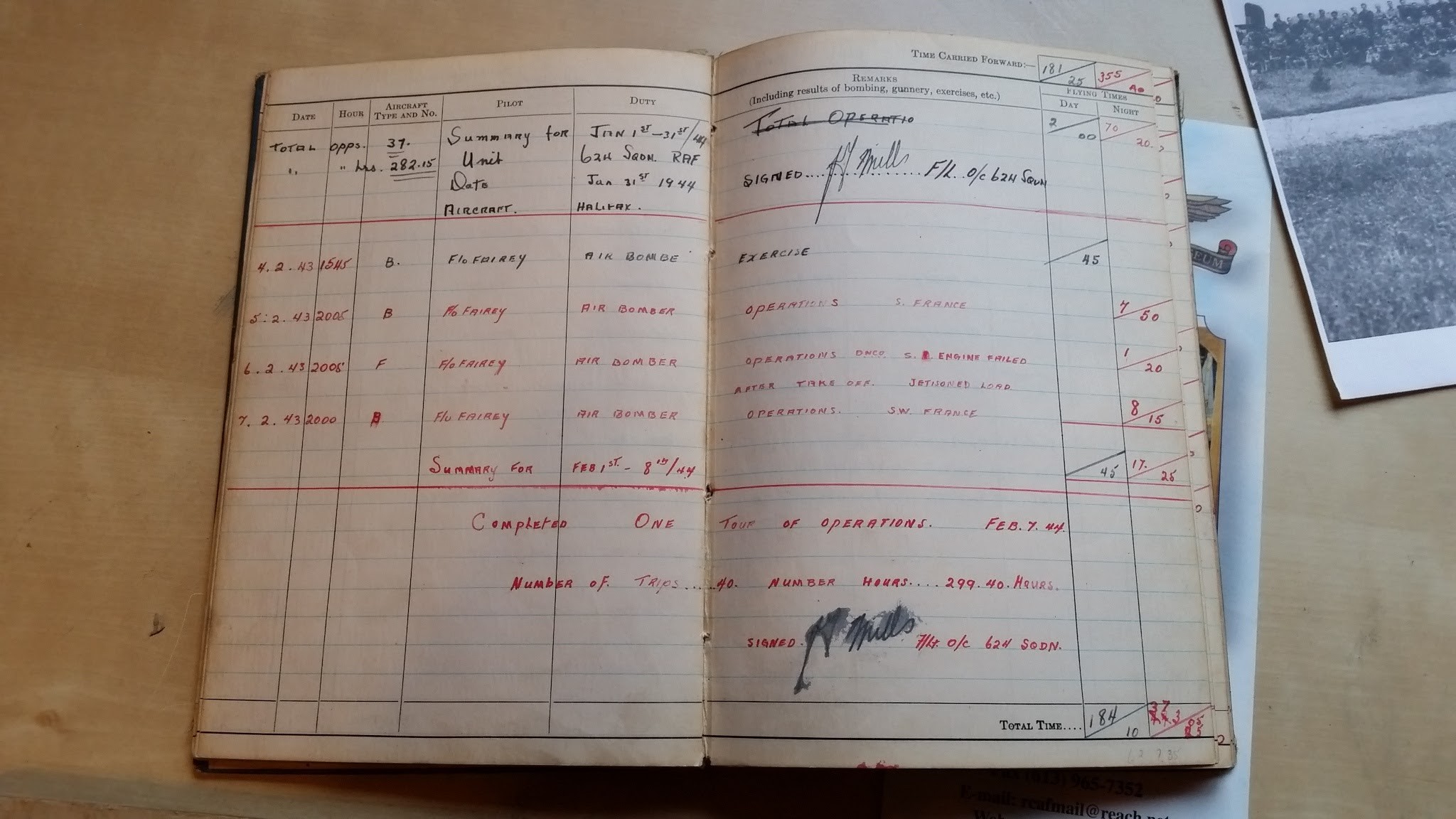

Squadron

624 RAF

Aircraft

Halifax & Stirling

Theater

Mediterranean

The Man in the Machine

Reality is a thin veil, and for Flight Sergeant John Douglas Paget, that veil was shredded at 20,000 feet. In the claustrophobic metal belly of a Halifax bomber, with engines roaring like mechanical beasts and the black void of night stretching endlessly below, Paget confronted the existential absurdity of war. Was he the pilot of his destiny or merely a component in the vast machinery of conflict? The Royal Canadian Air Force had trained him to navigate through flak-filled skies, but nothing could prepare him for navigating the labyrinth of his own consciousness.

The war existed in two dimensions for Paget: the physical reality of bombing runs over occupied Europe, and the psychological reality of questioning his own humanity with each payload released. In the quiet moments between missions, when the adrenaline subsided and the weight of his actions settled upon him, he wondered if the man who returned to base was the same one who had taken to the skies hours earlier. Each mission chipped away at his identity, replacing pieces of himself with the cold calculus of survival.

The Secret Squadron

624 Squadron RAF operated in the shadows of history, its missions classified, its existence barely acknowledged. Paget found himself part of this clandestine brotherhood, dropping agents and supplies behind enemy lines under the cover of darkness. The secrecy added another layer of psychological complexity to his service. How could one process experiences that couldn't be shared? How could one integrate memories that officially didn't exist?

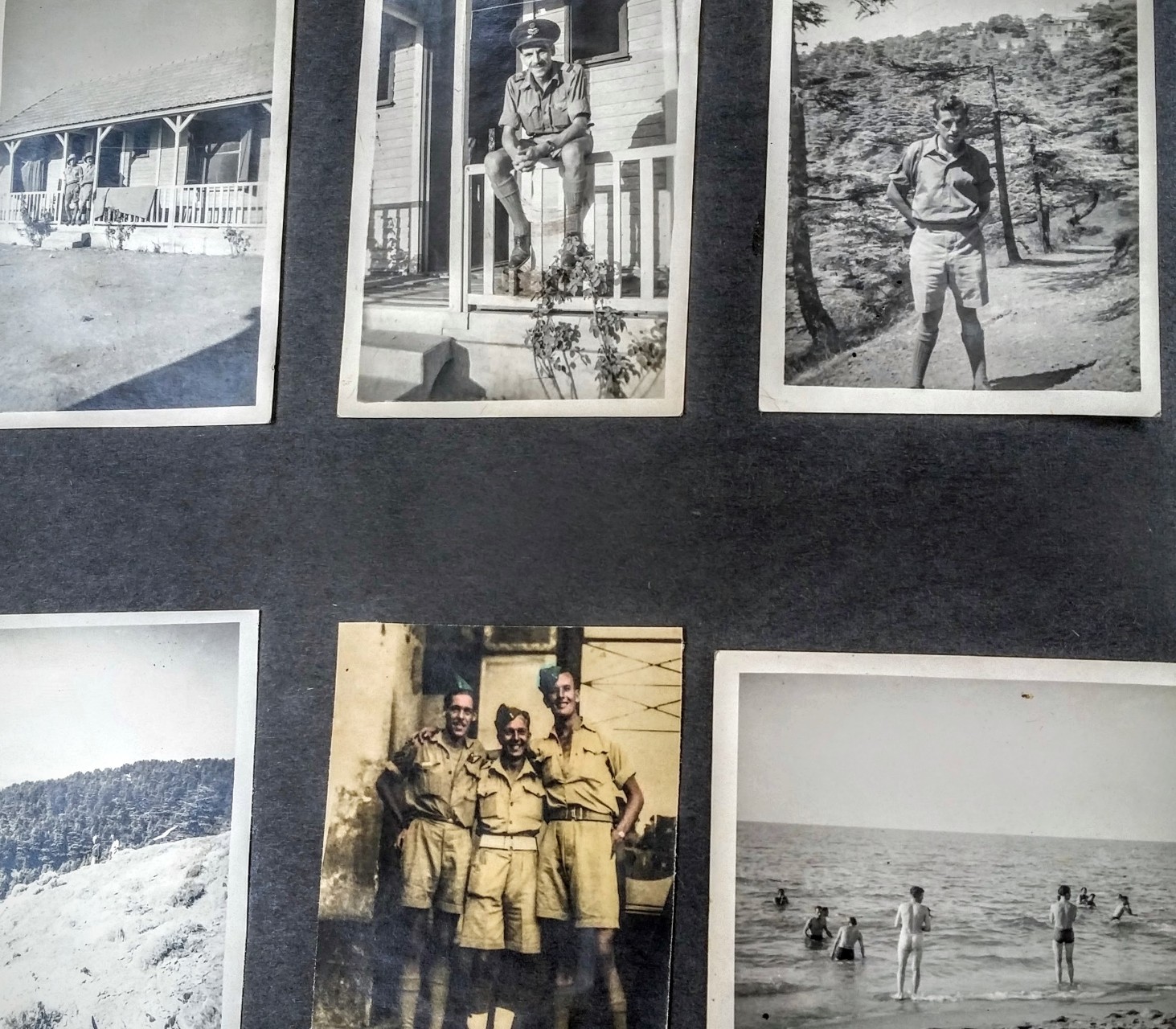

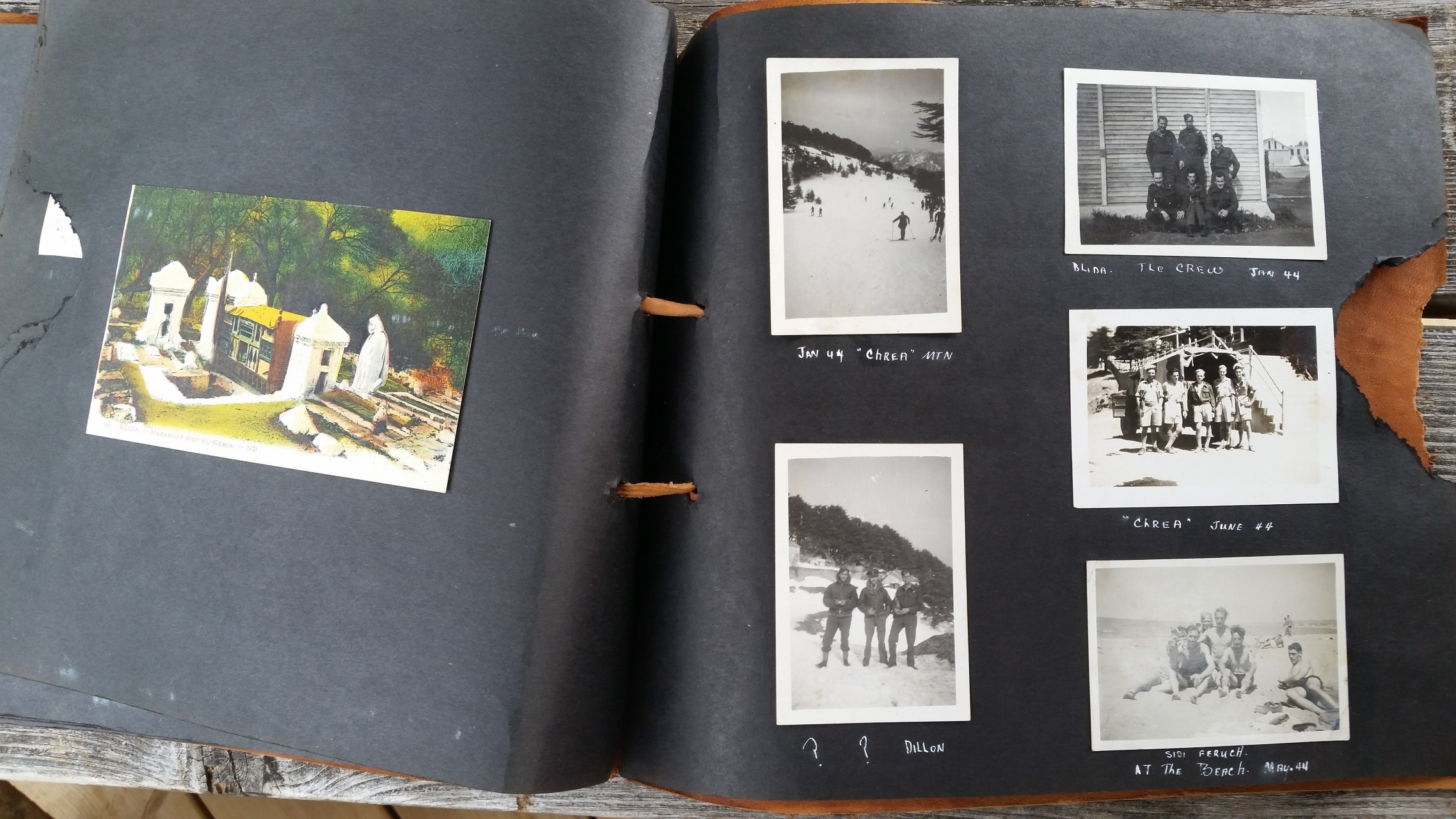

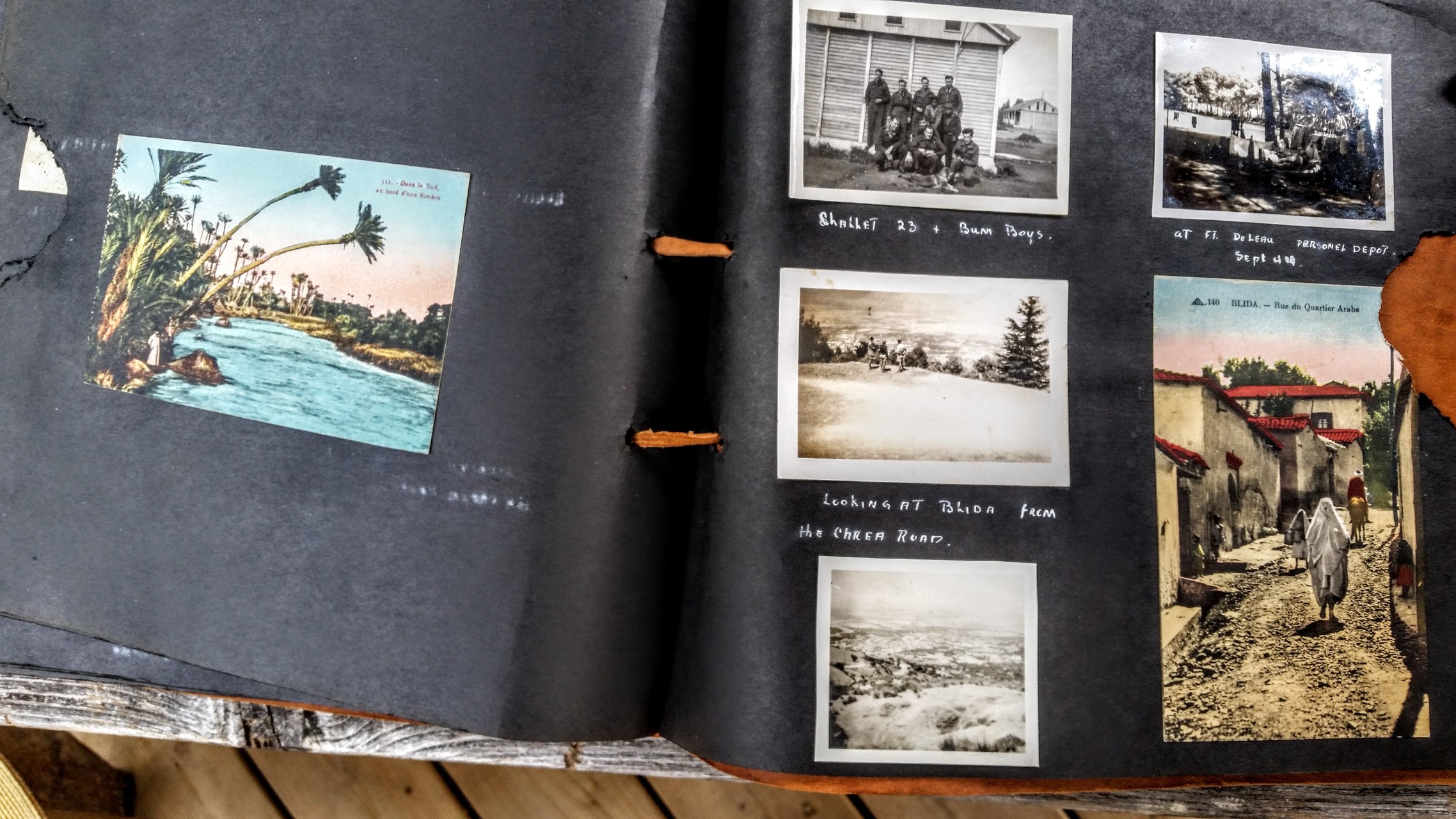

The Mediterranean theater presented its own unique paradoxes. While European skies were a symphony of destruction, the Mediterranean offered a surreal juxtaposition of natural beauty and human violence. Paget often flew over ancient civilizations—Rome, Carthage, Alexandria—releasing modern devastation upon landscapes that had witnessed millennia of conflict. The temporal disorientation was profound; he felt simultaneously connected to and disconnected from the long arc of human history.

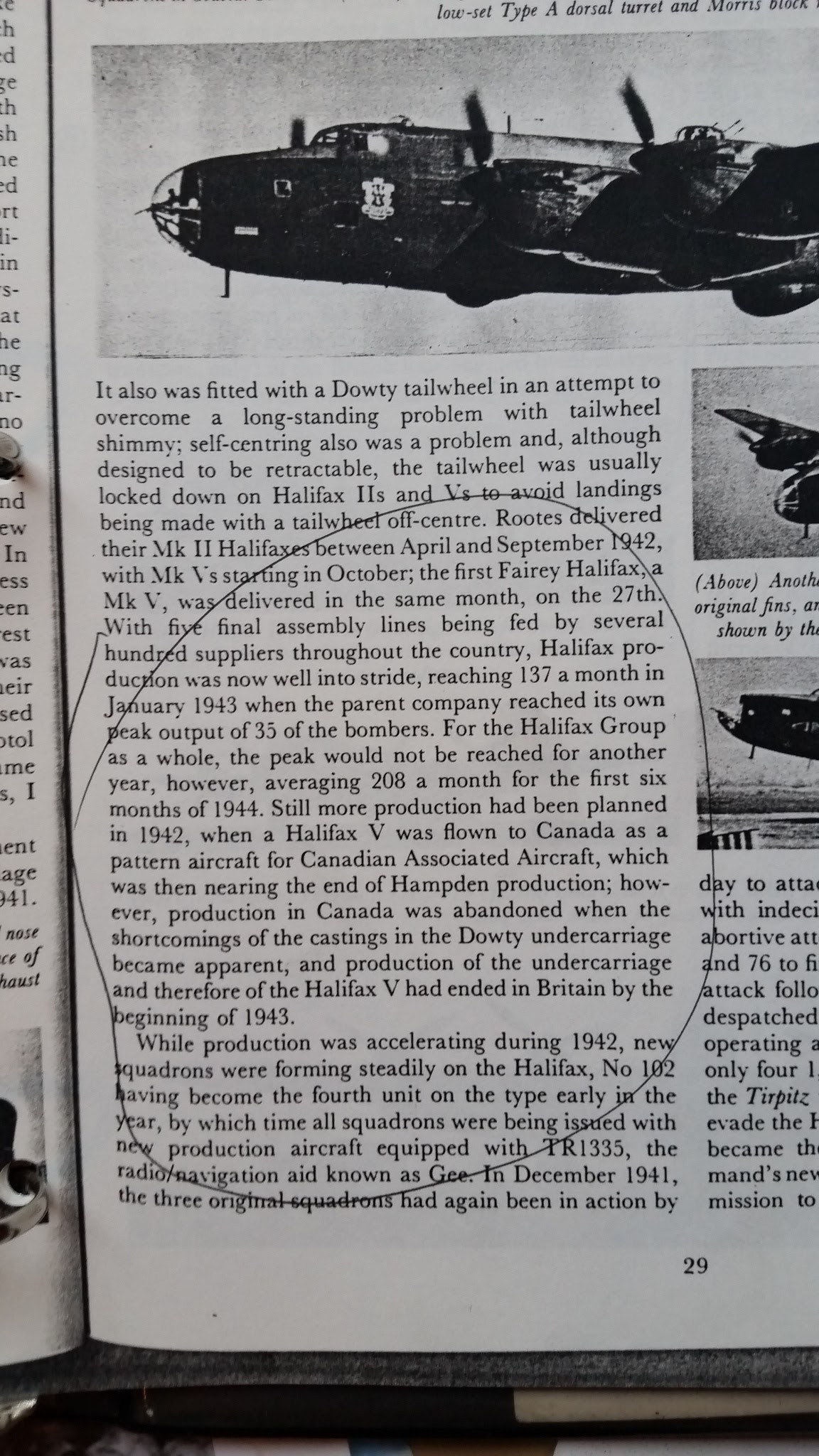

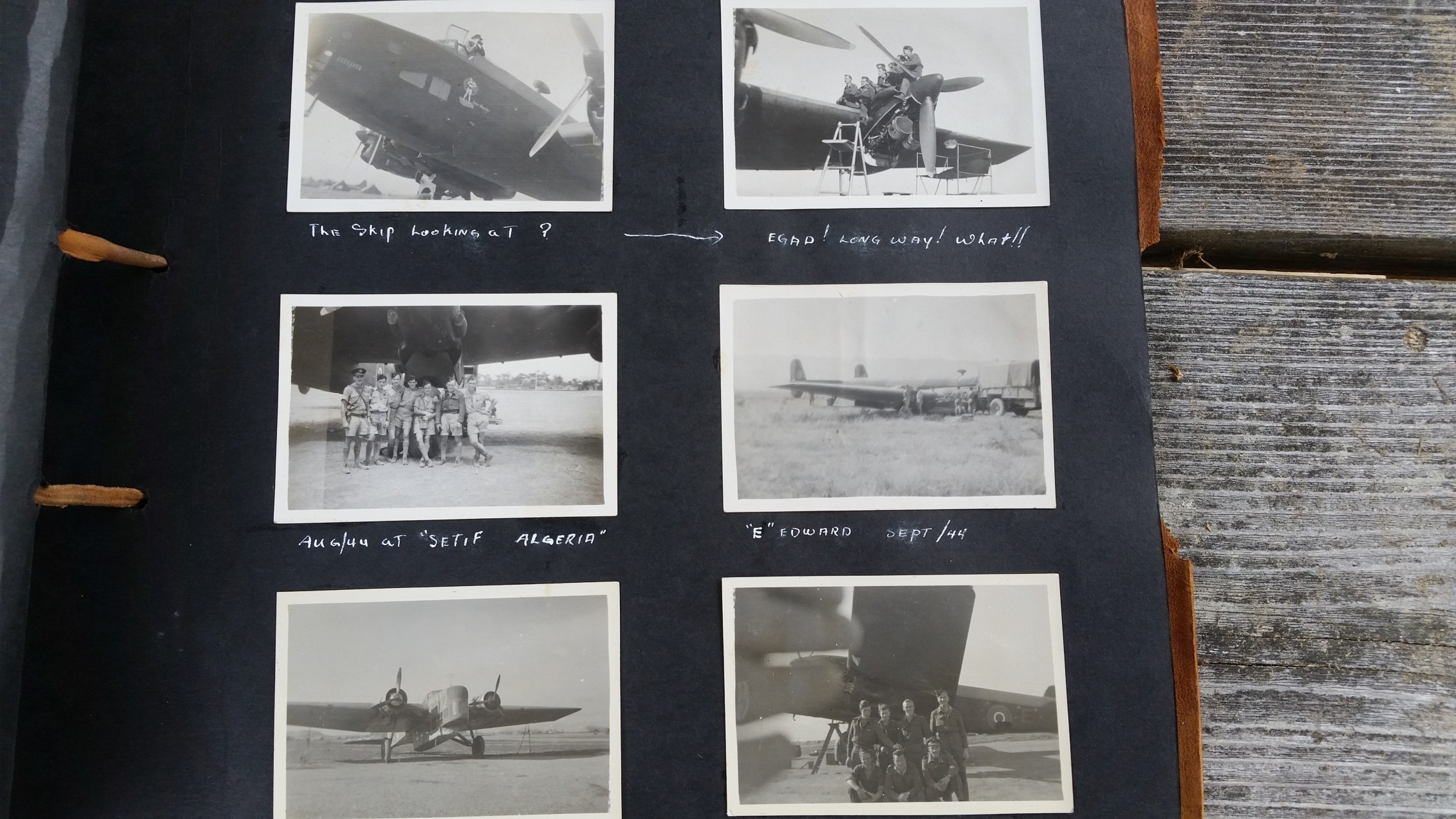

The Machines of War

The Halifax and Stirling bombers were more than aircraft to Paget; they were living entities with personalities and quirks. The Halifax, with its robust frame and reliable engines, was a trusted companion in the night sky. The Stirling, larger and more temperamental, demanded a symbiotic relationship between man and machine. Paget developed an almost intimate knowledge of these aircraft, their vibrations becoming an extension of his own nervous system, their mechanical sounds a language he had learned to interpret.

The relationship between bomber crews and their aircraft was a study in mutual dependence. The machines needed human operators to fulfill their purpose, while the humans needed the machines to survive the hostile environment of combat. This interdependence created a strange bond—one of both reverence and resentment. Paget often found himself talking to his aircraft, attributing human qualities to its mechanical responses, a coping mechanism in a world where the line between animate and inanimate had grown perilously thin.

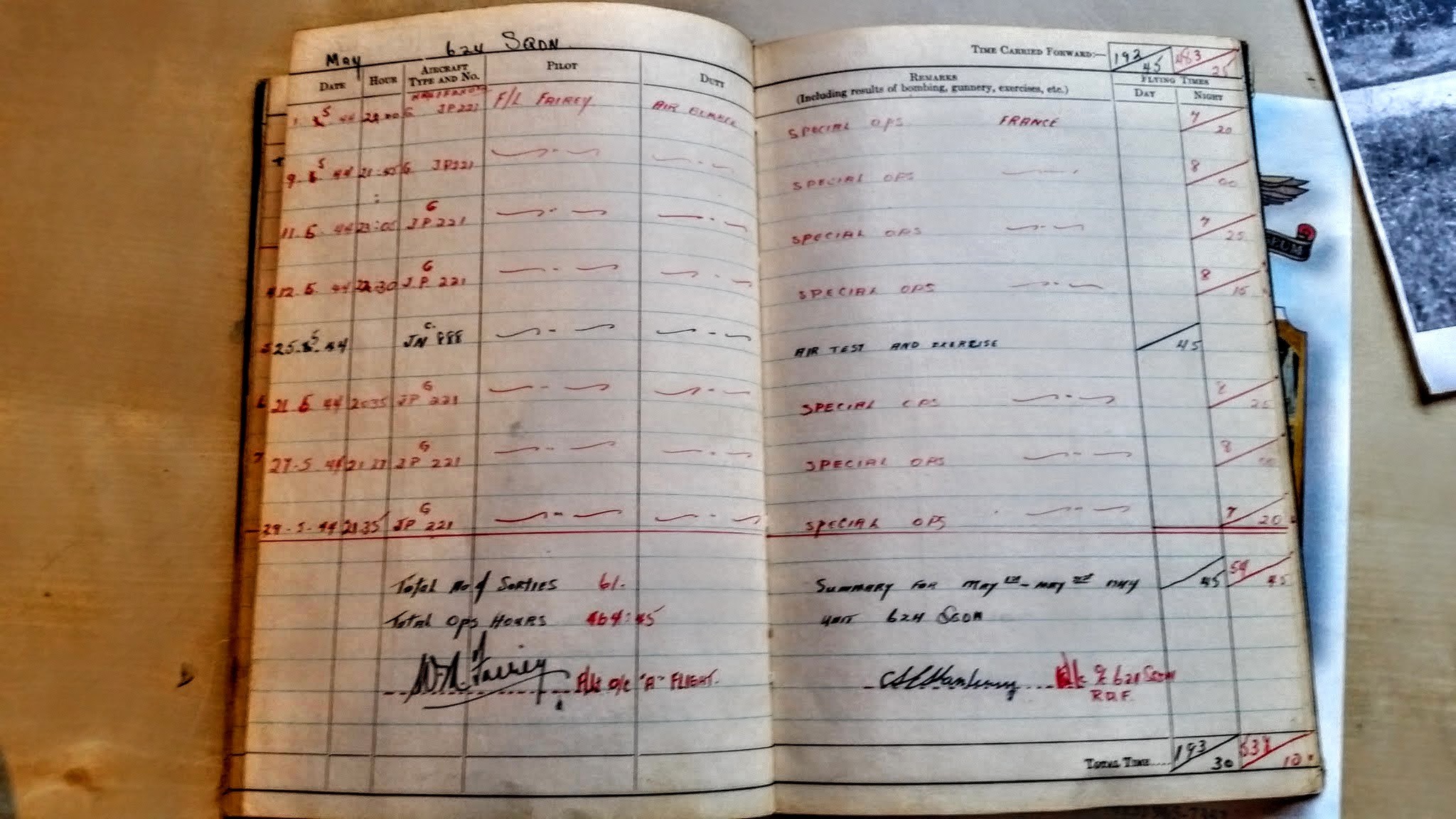

Paget joins 624 Squadron RAF as the Allies begin their strategic bombing campaign in preparation for the invasion of Europe. The psychological toll of these operations is immense, with crews facing survival rates as low as 50% for a full tour of duty.

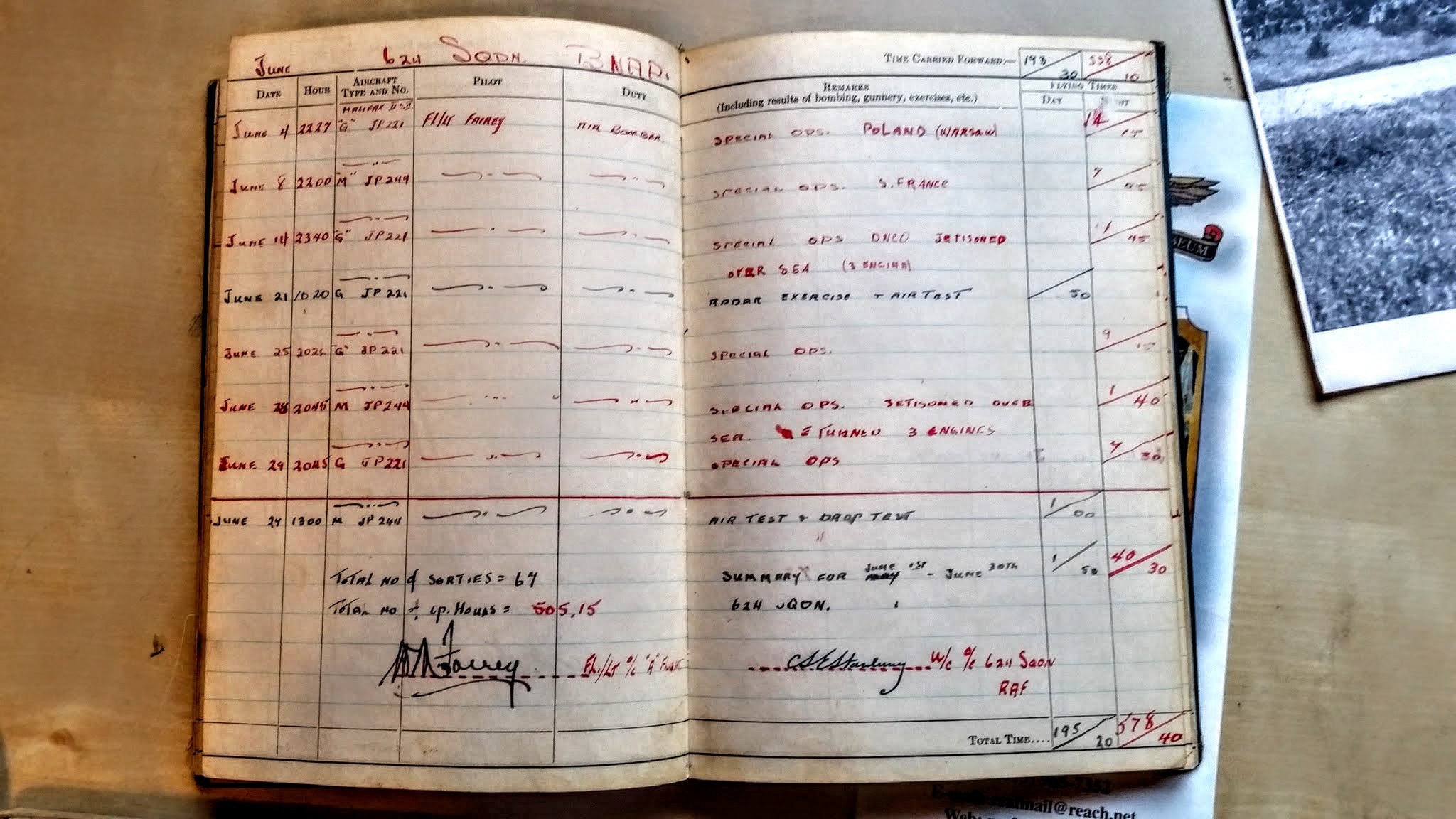

D-Day operations mark a turning point in the war. Paget participates in missions to disrupt German communications and supply lines, flying under conditions of extreme stress and moral ambiguity. The reality of war becomes increasingly surreal as the conflict intensifies.

As the war draws to a close, Paget confronts the aftermath of his service. The transition from wartime to peacetime proves as challenging as combat itself, as he struggles to reconcile the man he was with the man he has become.

The Nature of Reality

War has a way of distorting perception, and for Paget, this distortion became permanent. The world he returned to after the war seemed somehow unreal, a simulation of the life he had left behind. The mundane concerns of civilian life paled in comparison to the life-and-death decisions he had made nightly. How does one readjust to a world where the stakes are no longer existential?

The psychological scars of bomber operations ran deep. Paget, like many of his comrades, suffered from what would later be recognized as PTSD, but in the 1940s, it was dismissed as "shell shock" or "combat fatigue." The true nature of his trauma remained unexamined, his experiences too alien for a society eager to put the war behind it. He carried the weight of his memories alone, a ghost in his own life, haunted by the echoes of engines and the specters of those who didn't return.

Legacy and Memory

John Douglas Paget's story is not just a military record; it's a meditation on the nature of identity, reality, and memory. His service in 624 Squadron represents a chapter in human history when the boundaries between the individual and the collective, the human and the technological, were being redrawn. The questions he grappled with—questions of agency, morality, and the meaning of service—remain relevant in our increasingly complex world.

As we look back on Paget's service, we are reminded that history is not merely a collection of facts and figures, but a tapestry of human experiences, each one unique yet connected to the larger patterns of our shared existence. His story challenges us to consider the true cost of conflict, not just in terms of lives lost, but in terms of identities altered and realities distorted.

Further Exploration

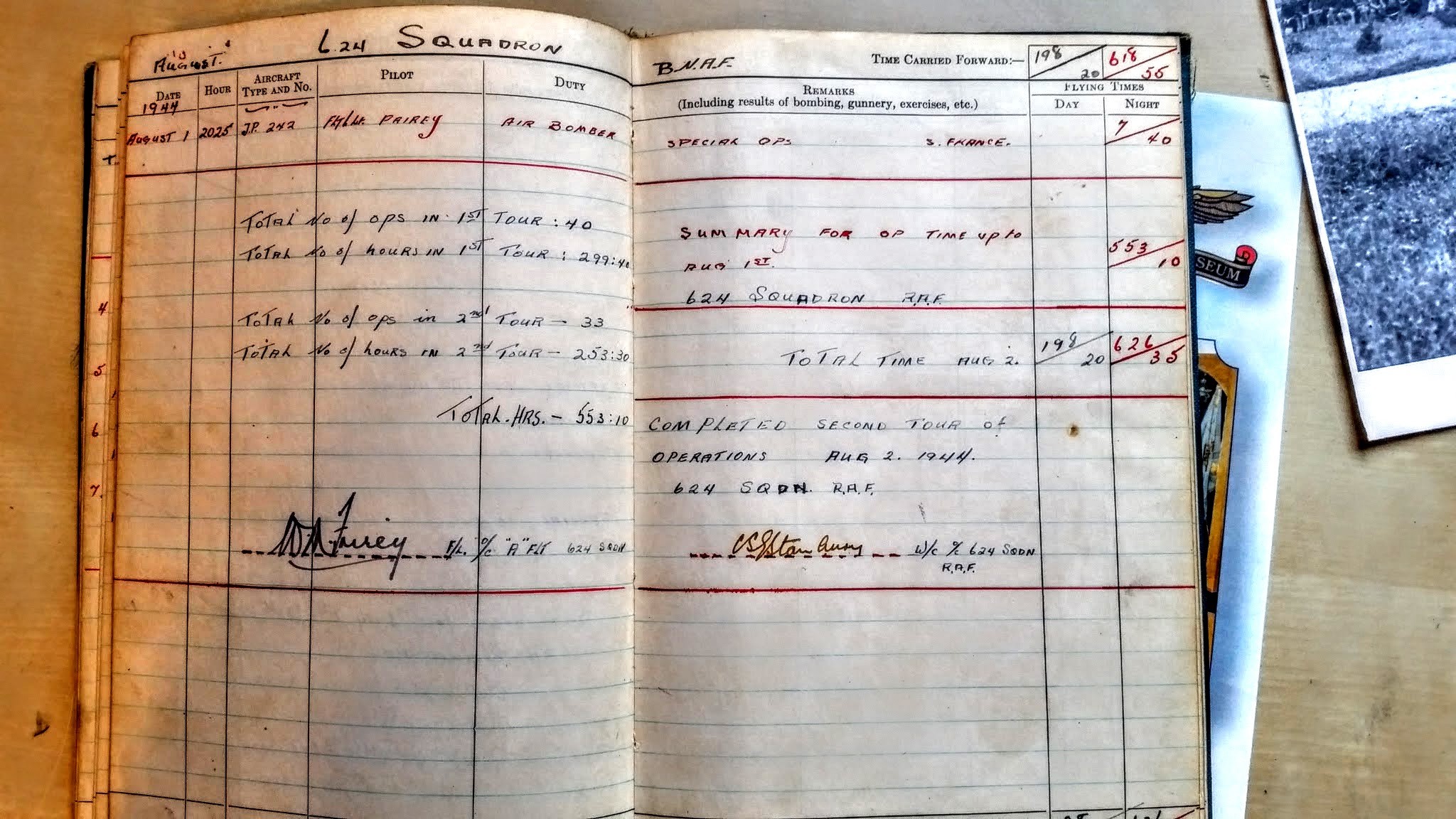

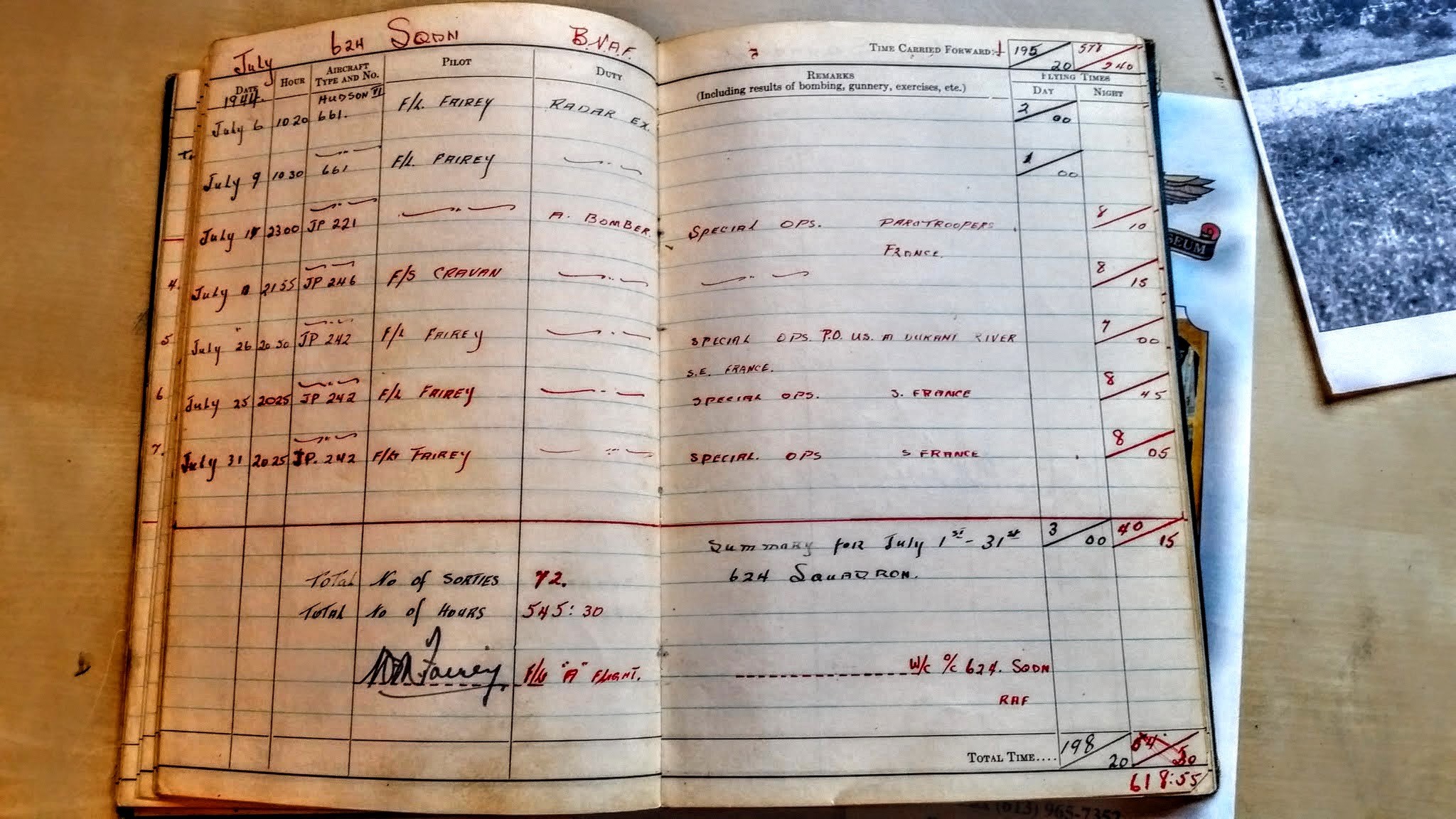

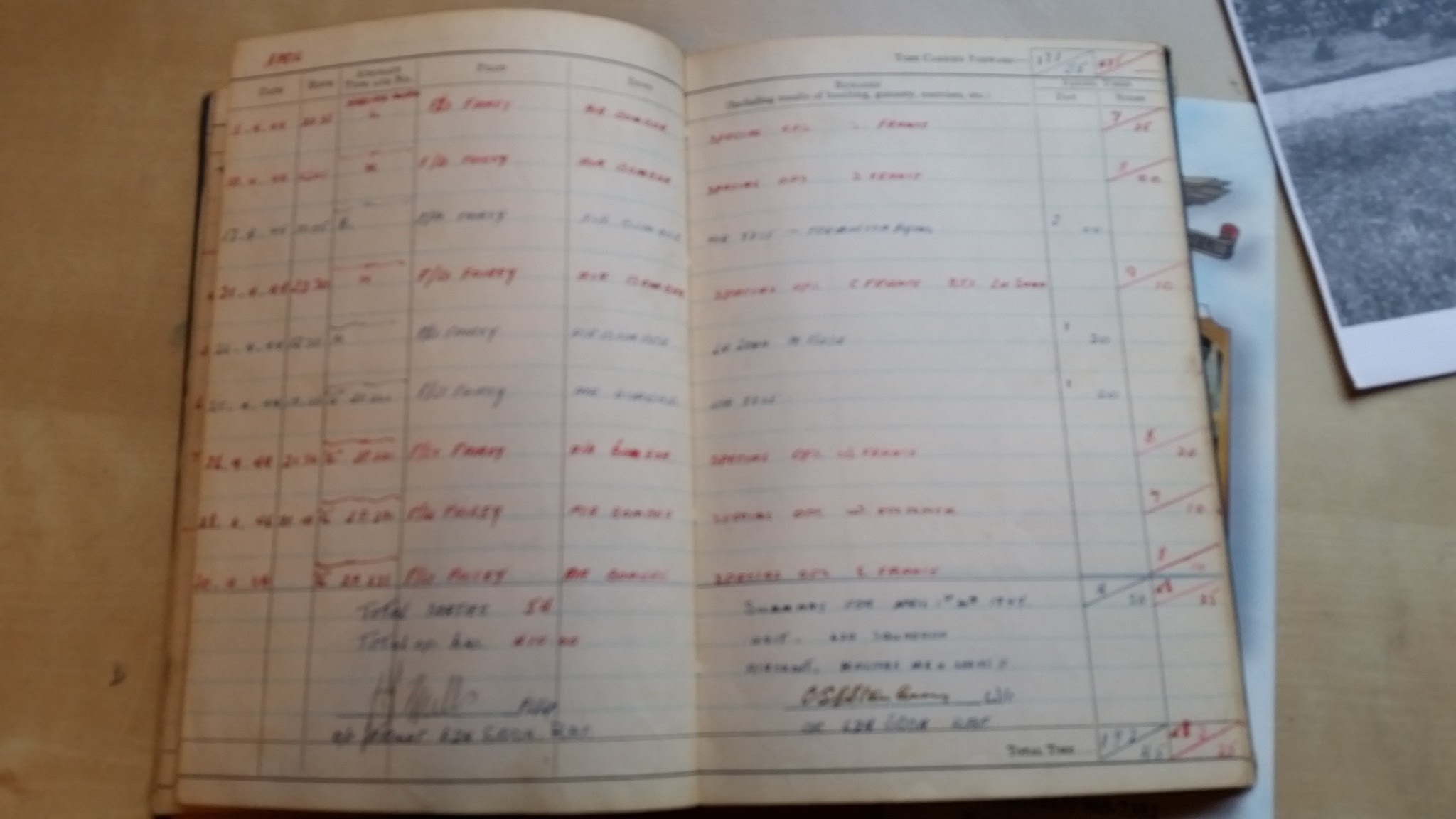

- 624 Squadron Official Records: Limited documentation exists due to the classified nature of their operations

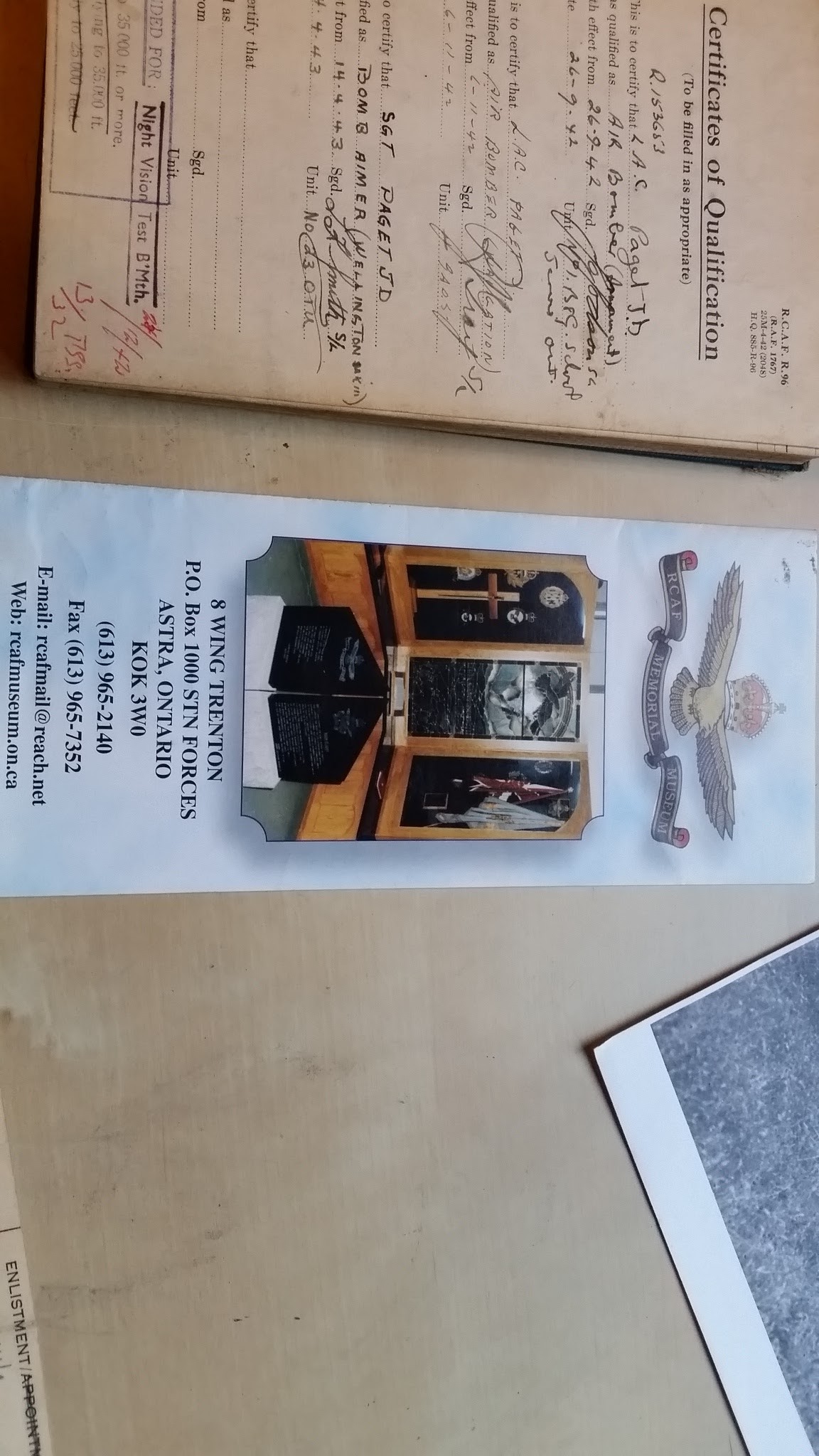

- Bomber Command Museum of Canada: Preserves the stories of RCAF bomber crews

- The Secret War: A documentary on special operations squadrons like 624

- Library and Archives Canada: Holds personnel records and mission reports

- No Prouder Place: A comprehensive history of Canadians in Bomber Command

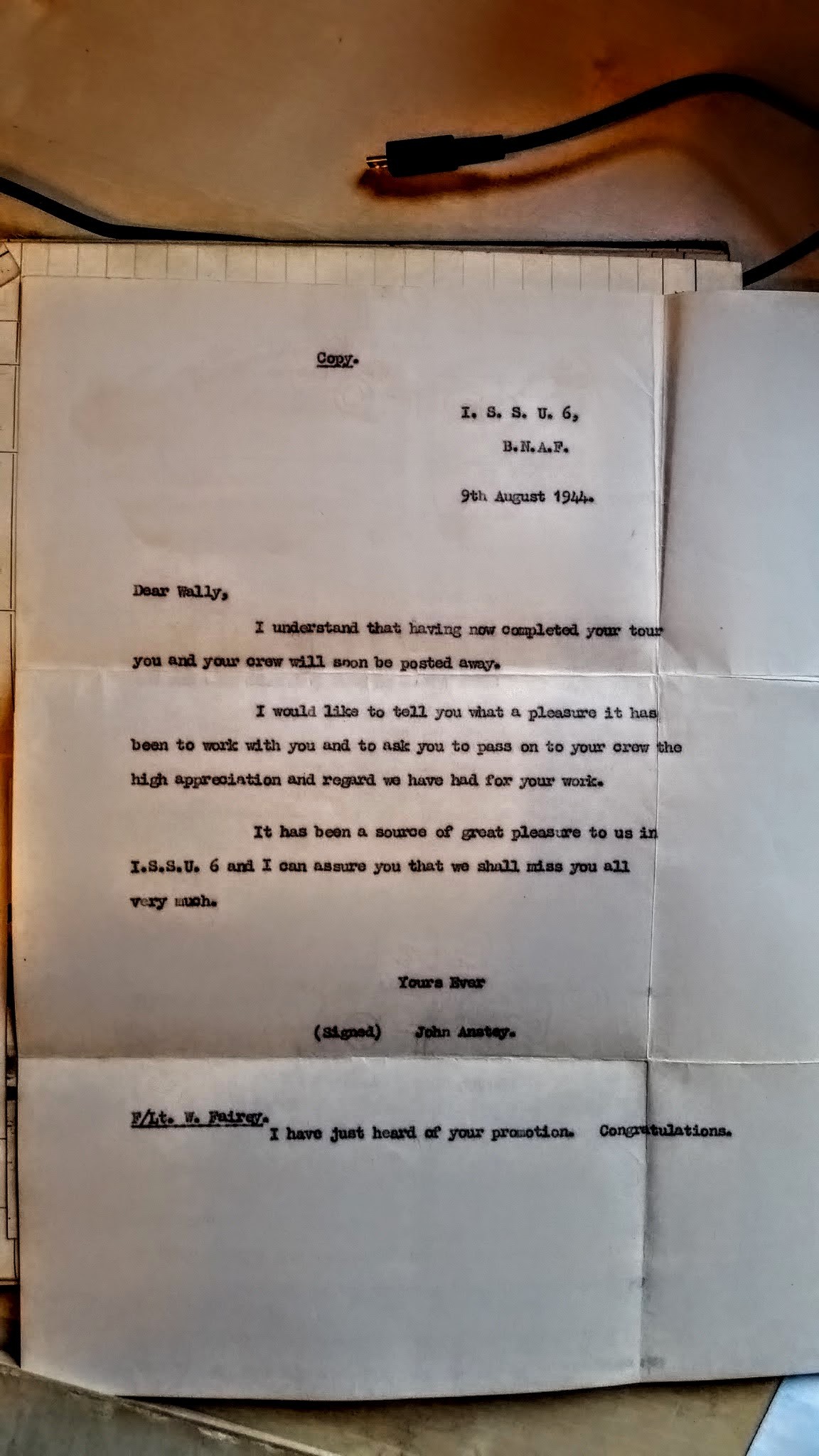

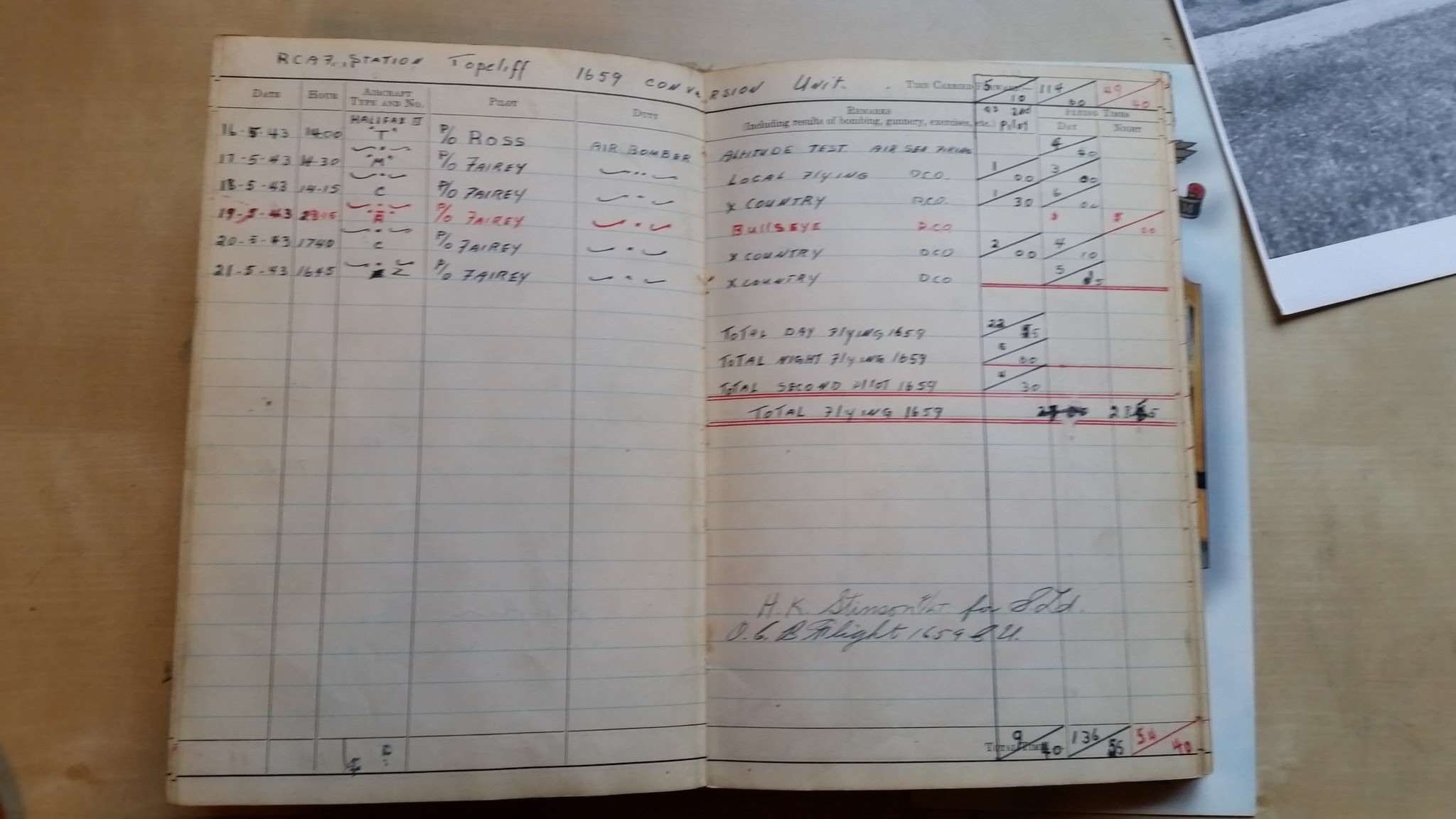

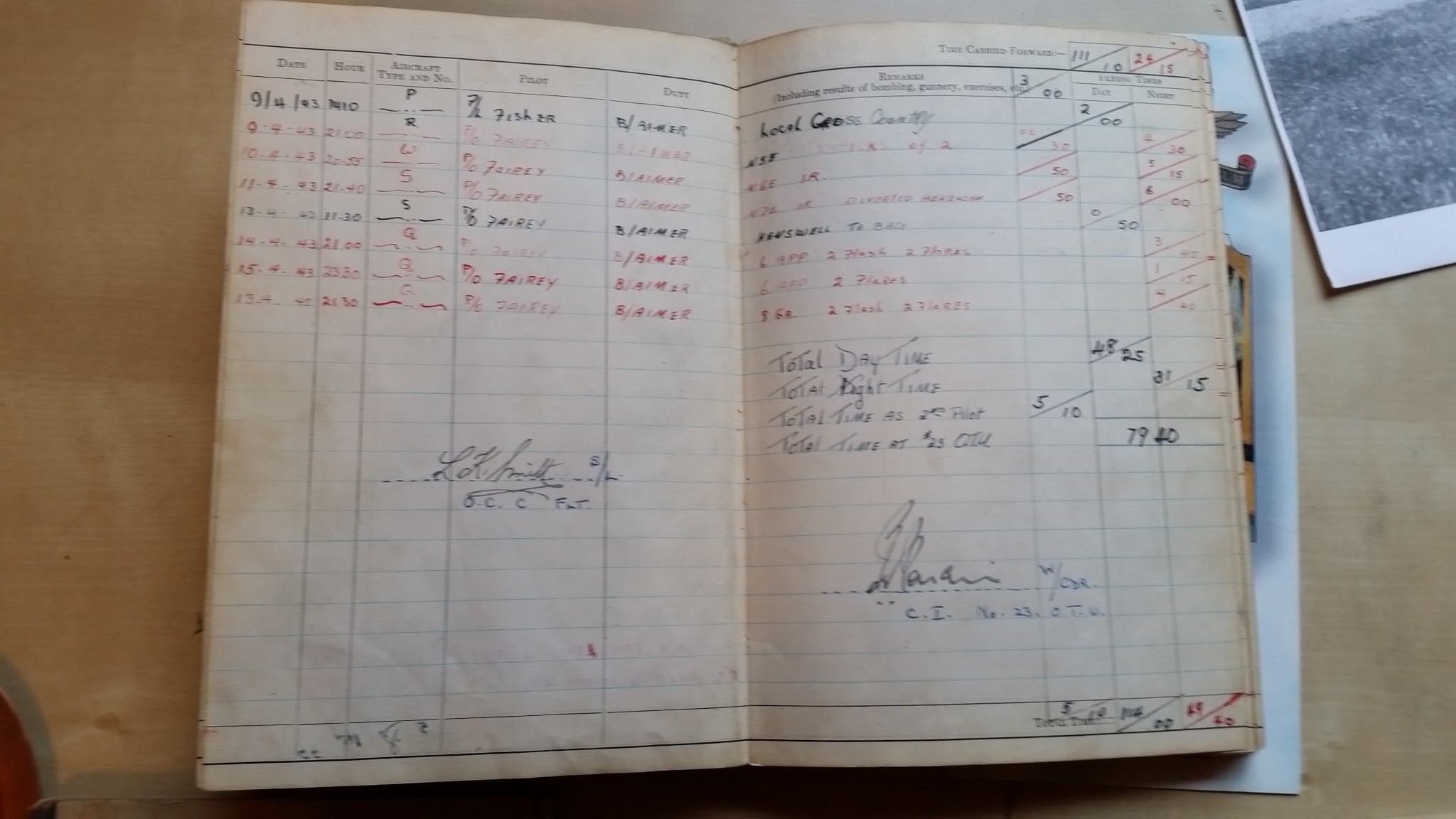

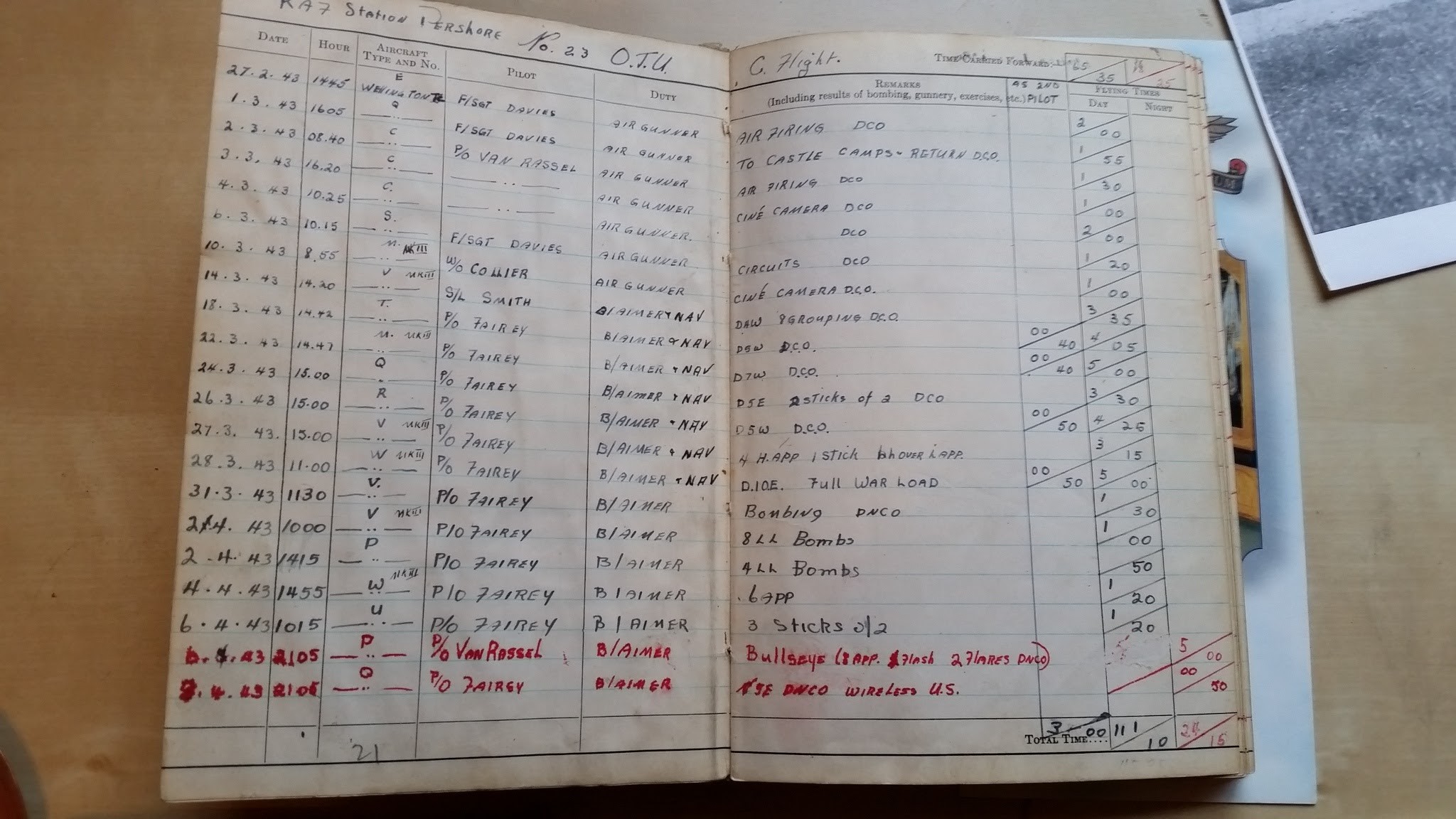

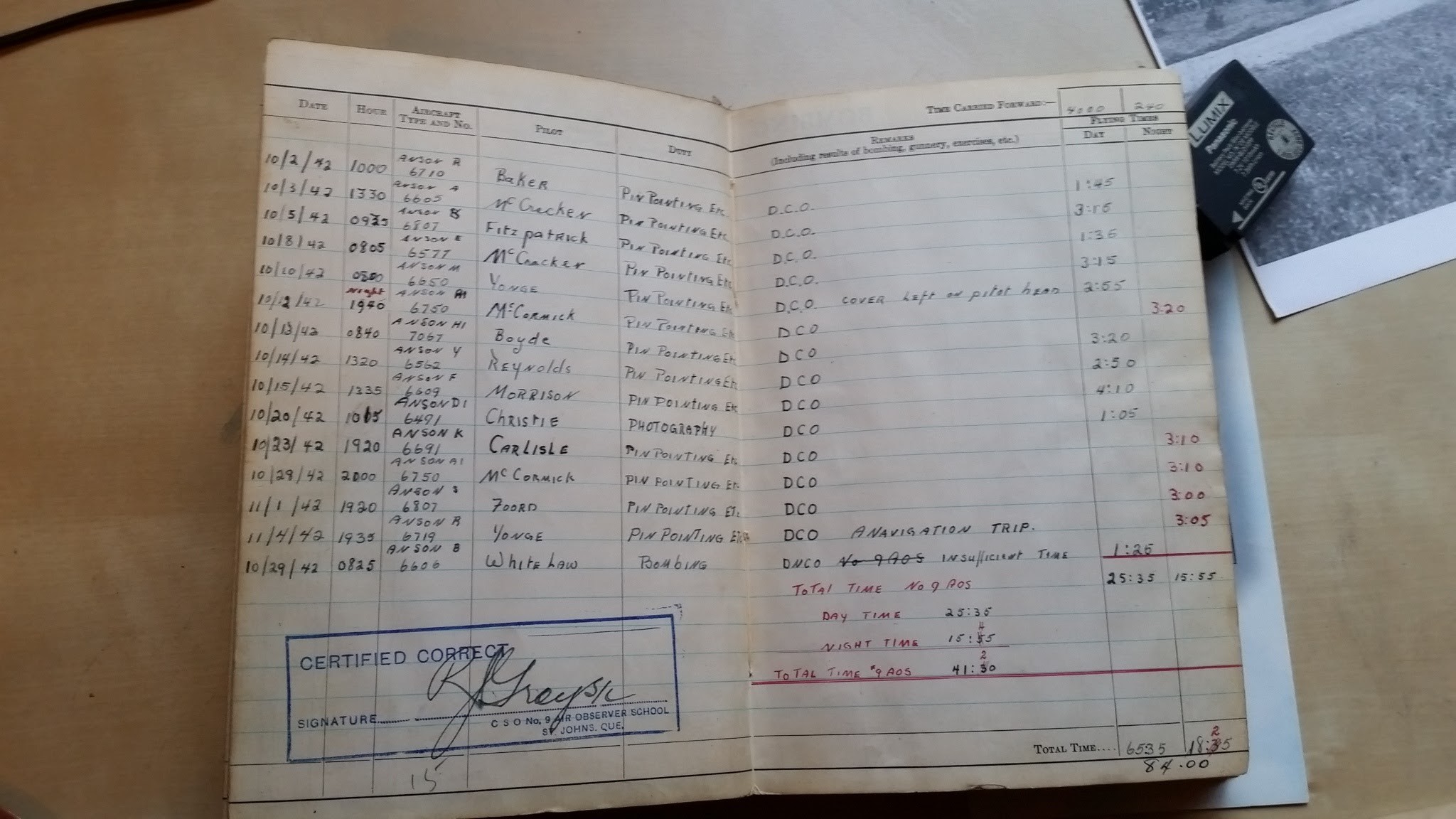

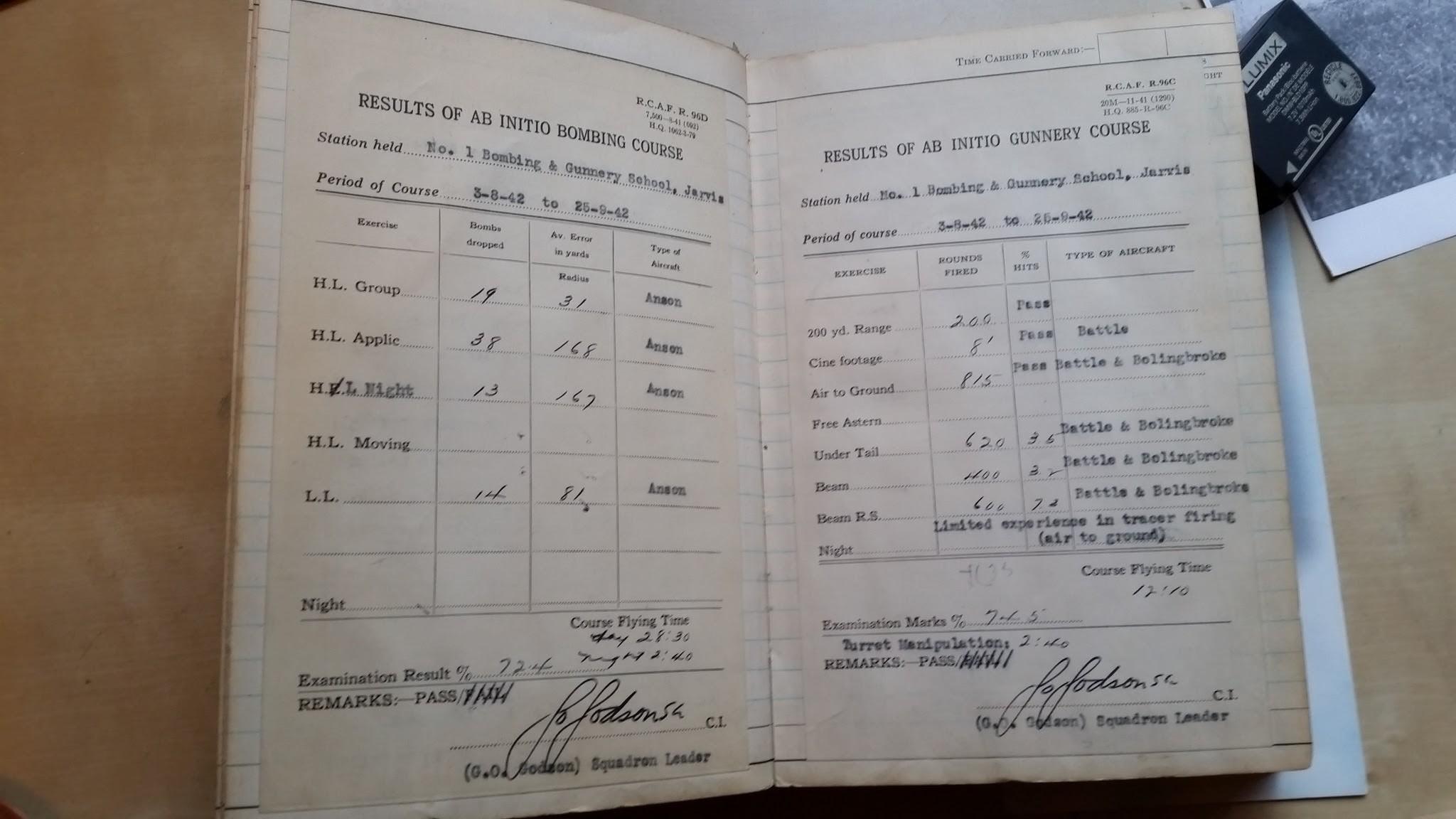

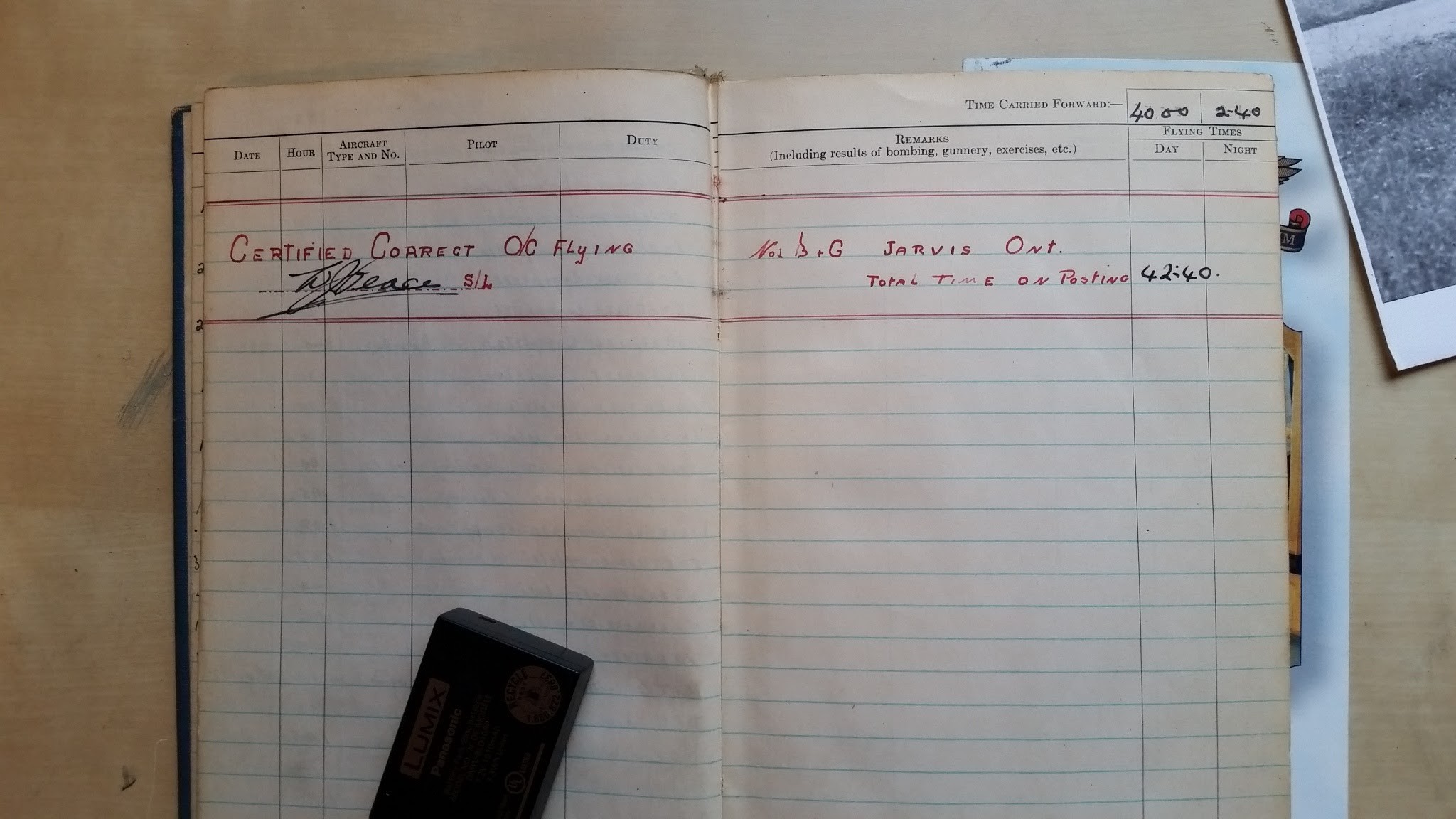

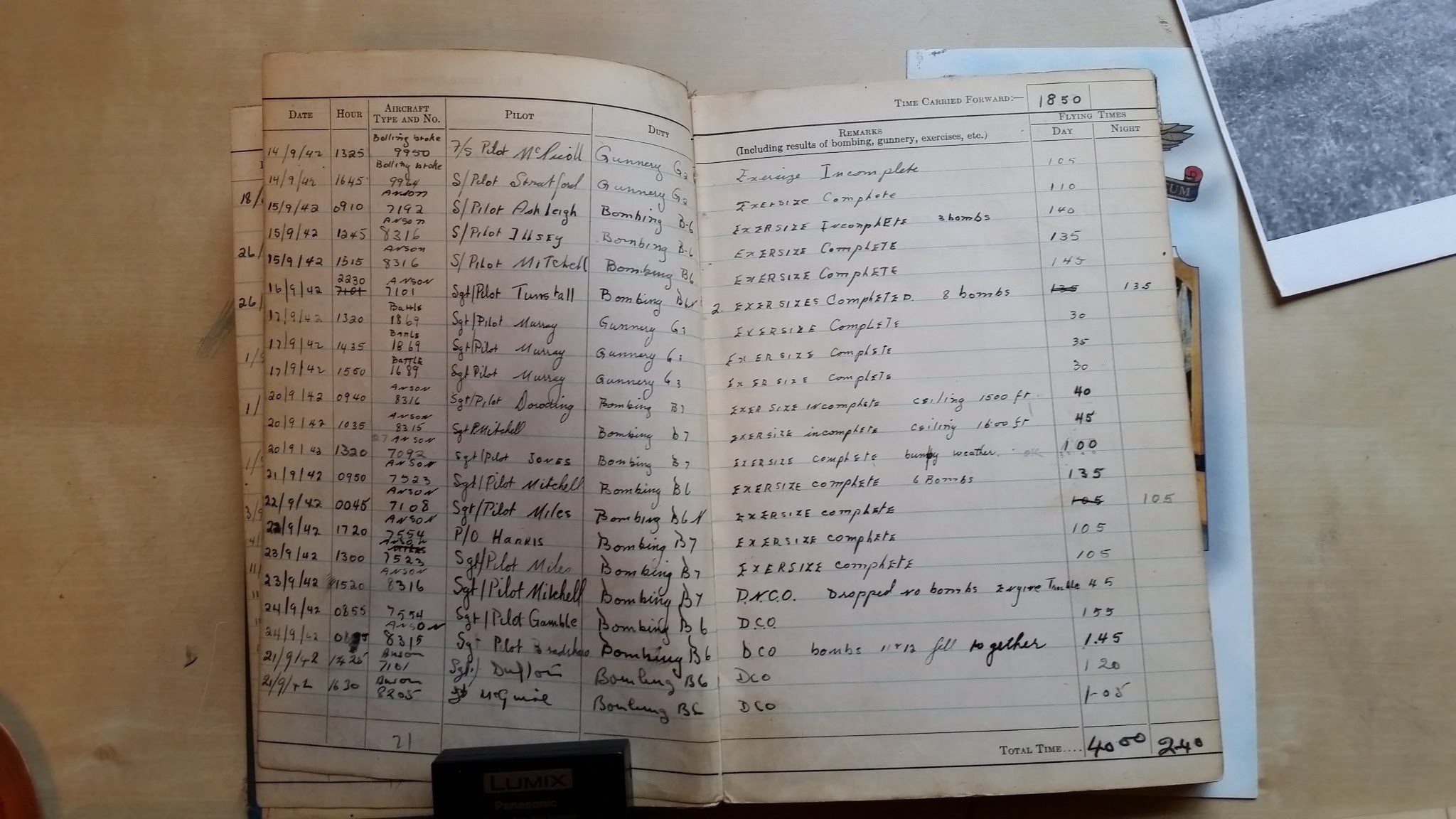

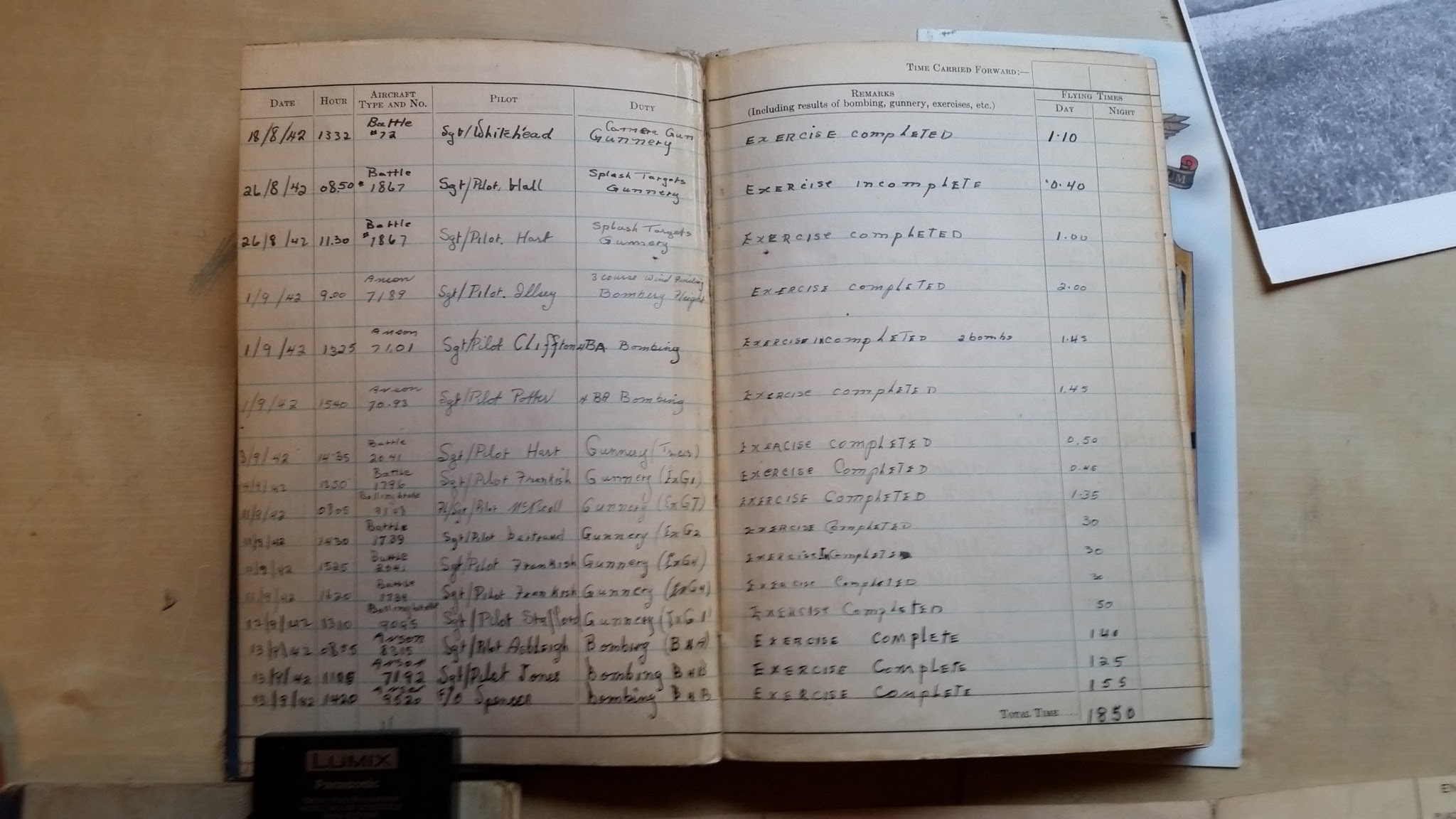

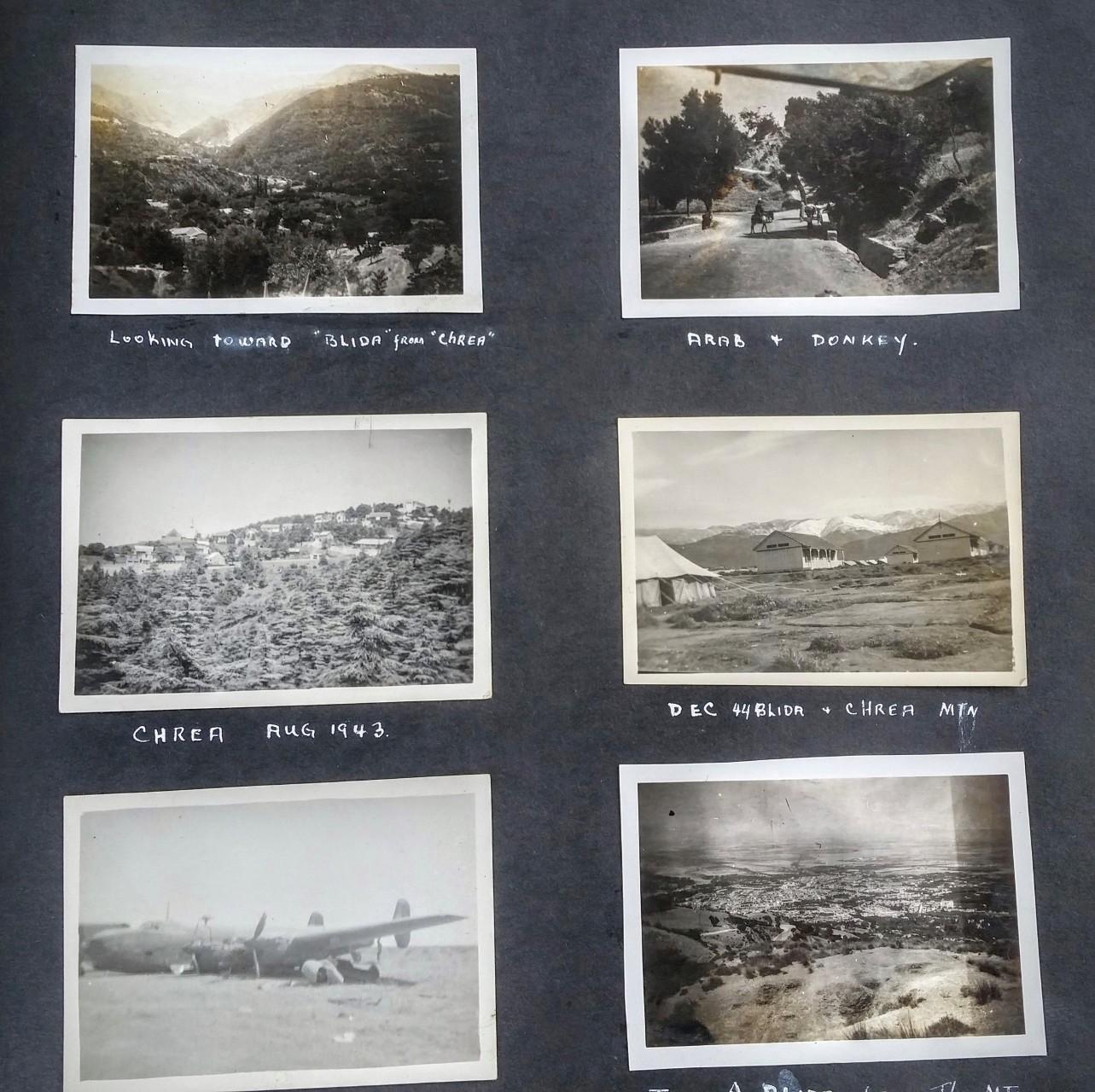

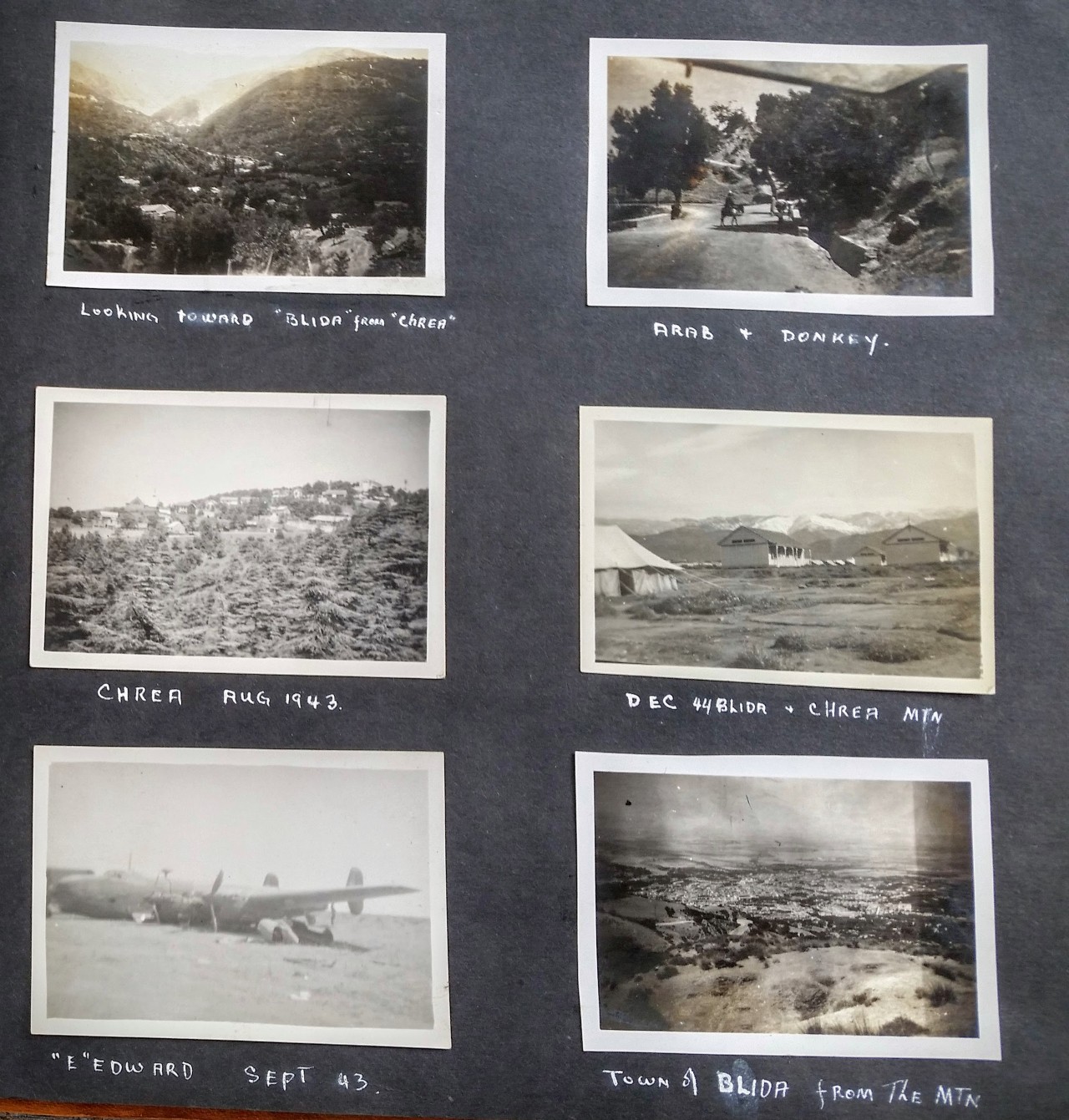

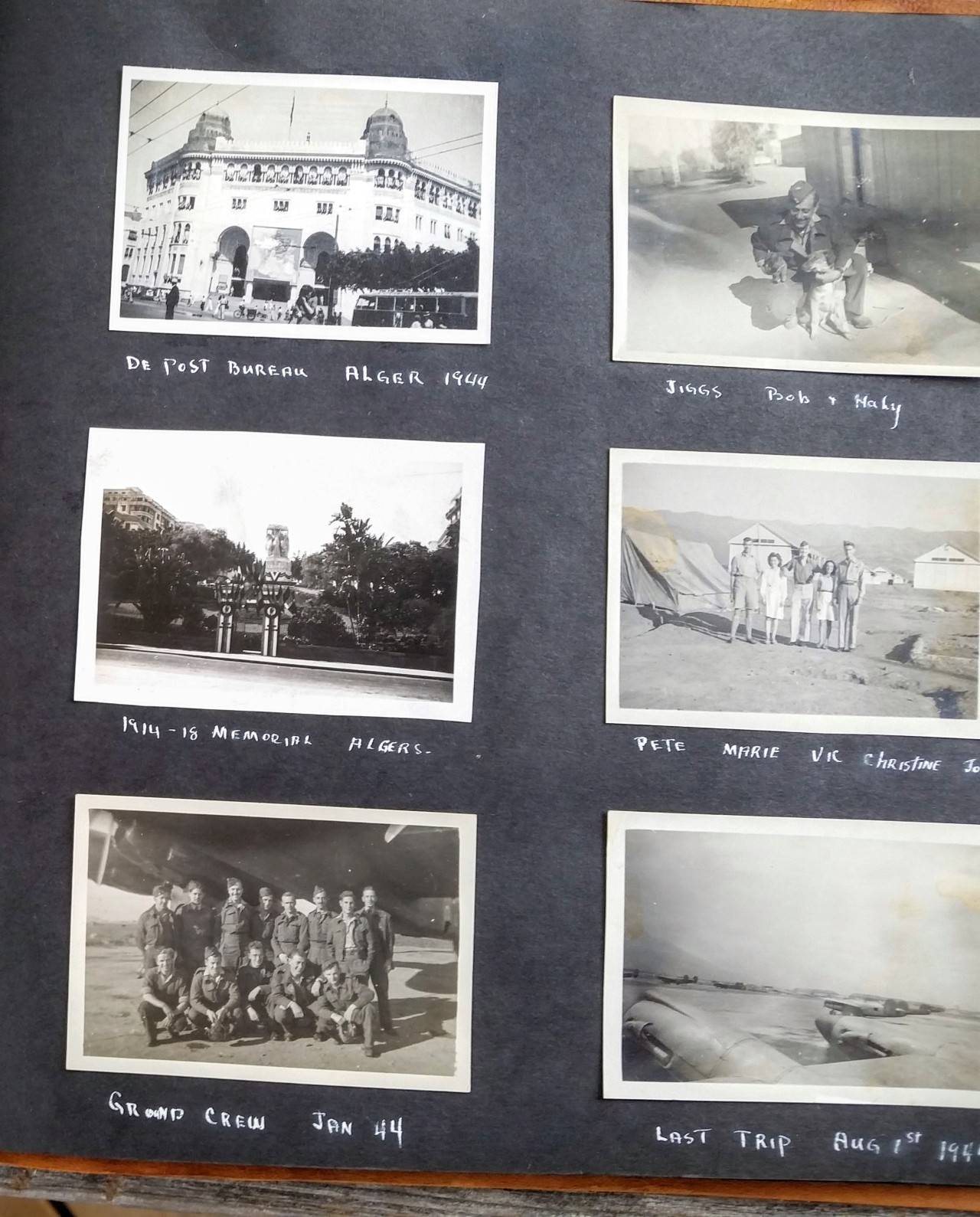

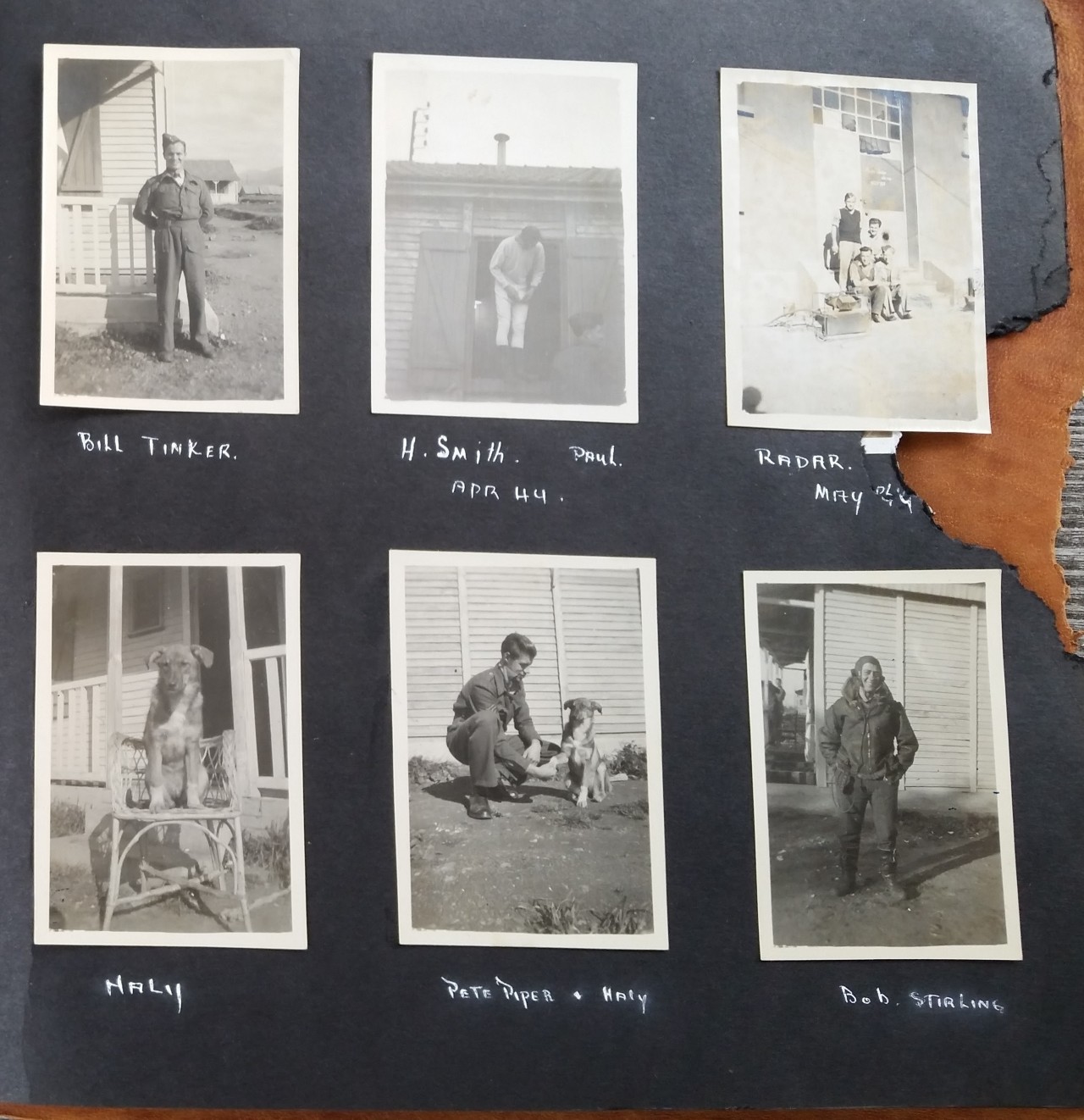

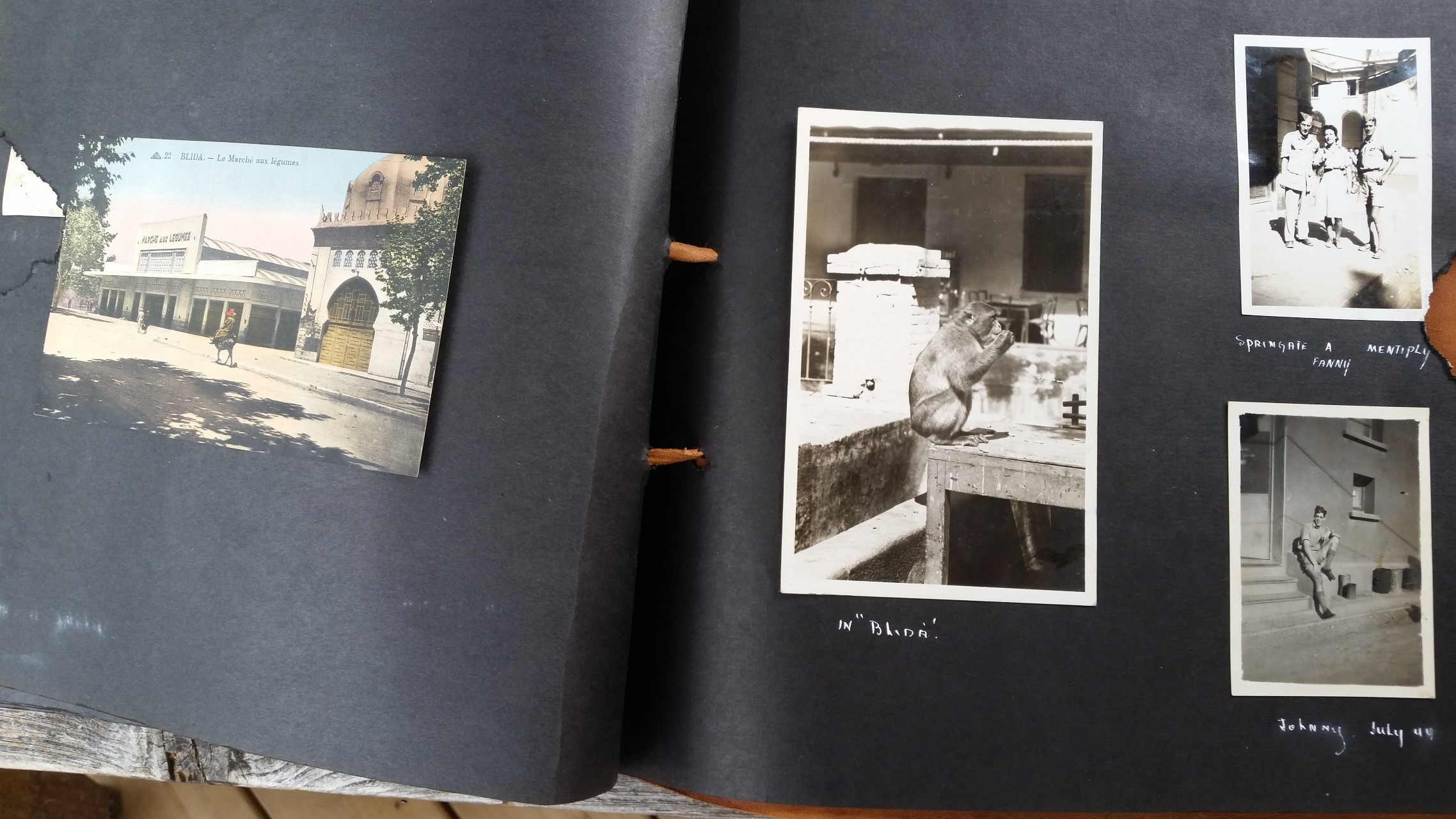

Archival Photographs and Documents