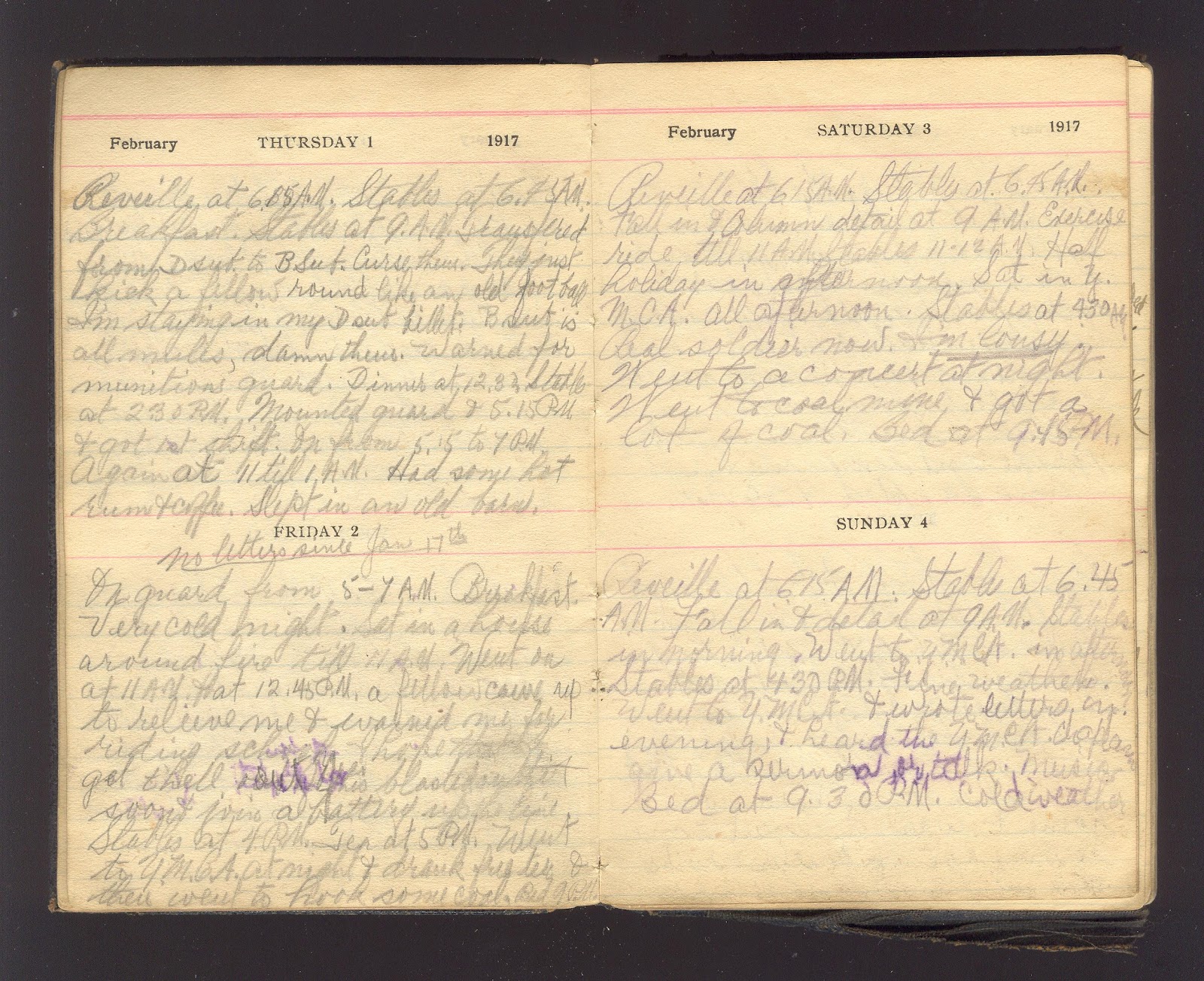

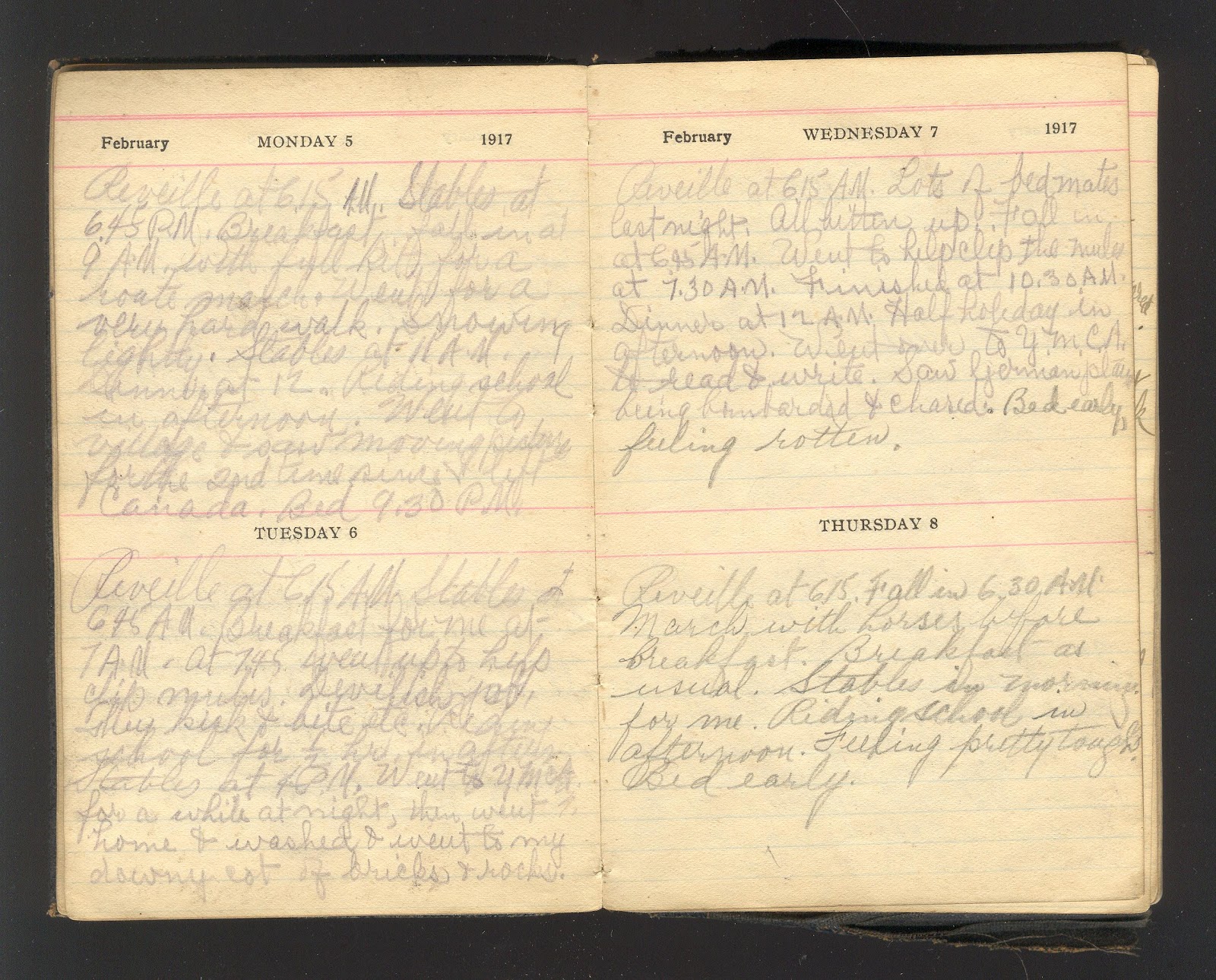

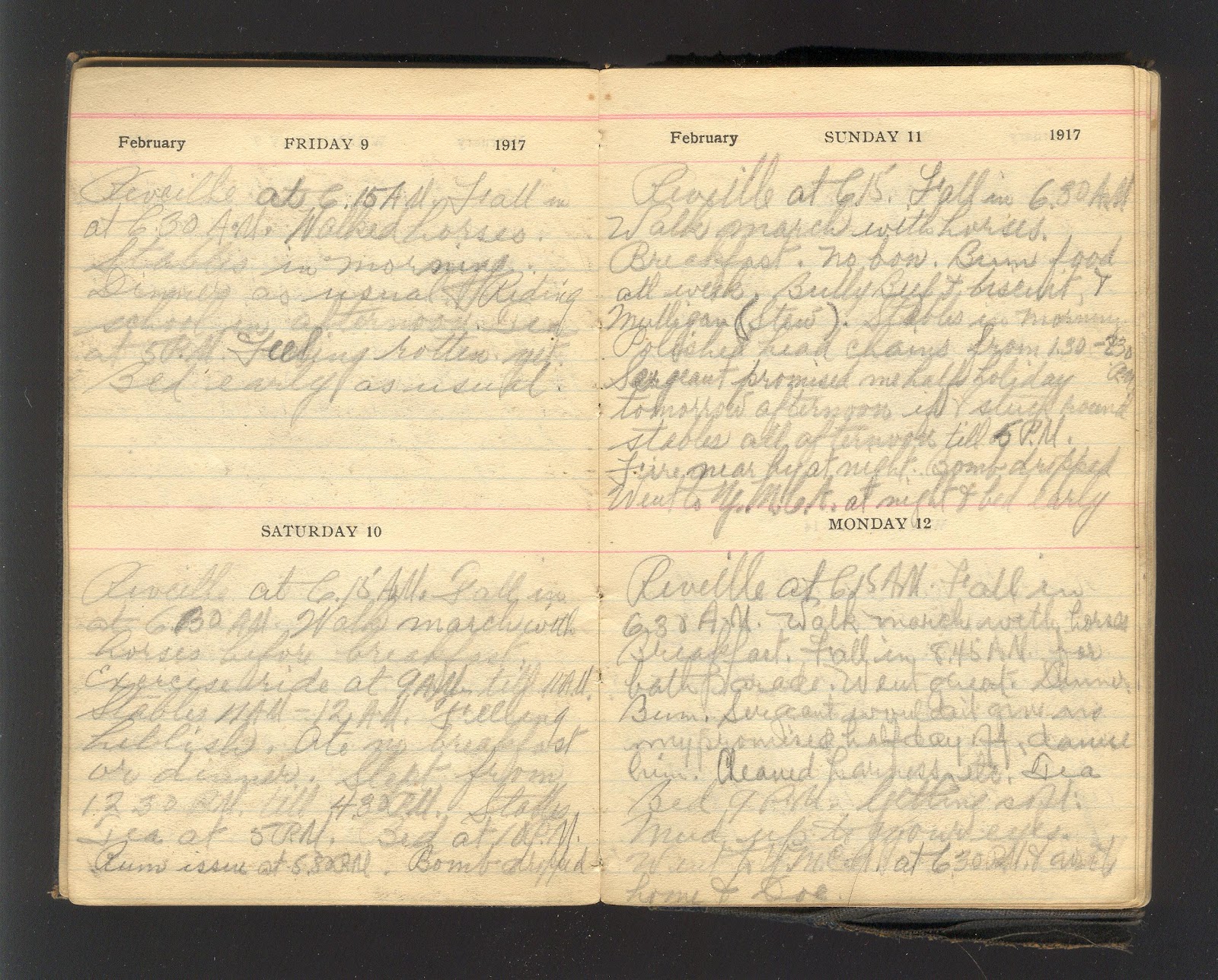

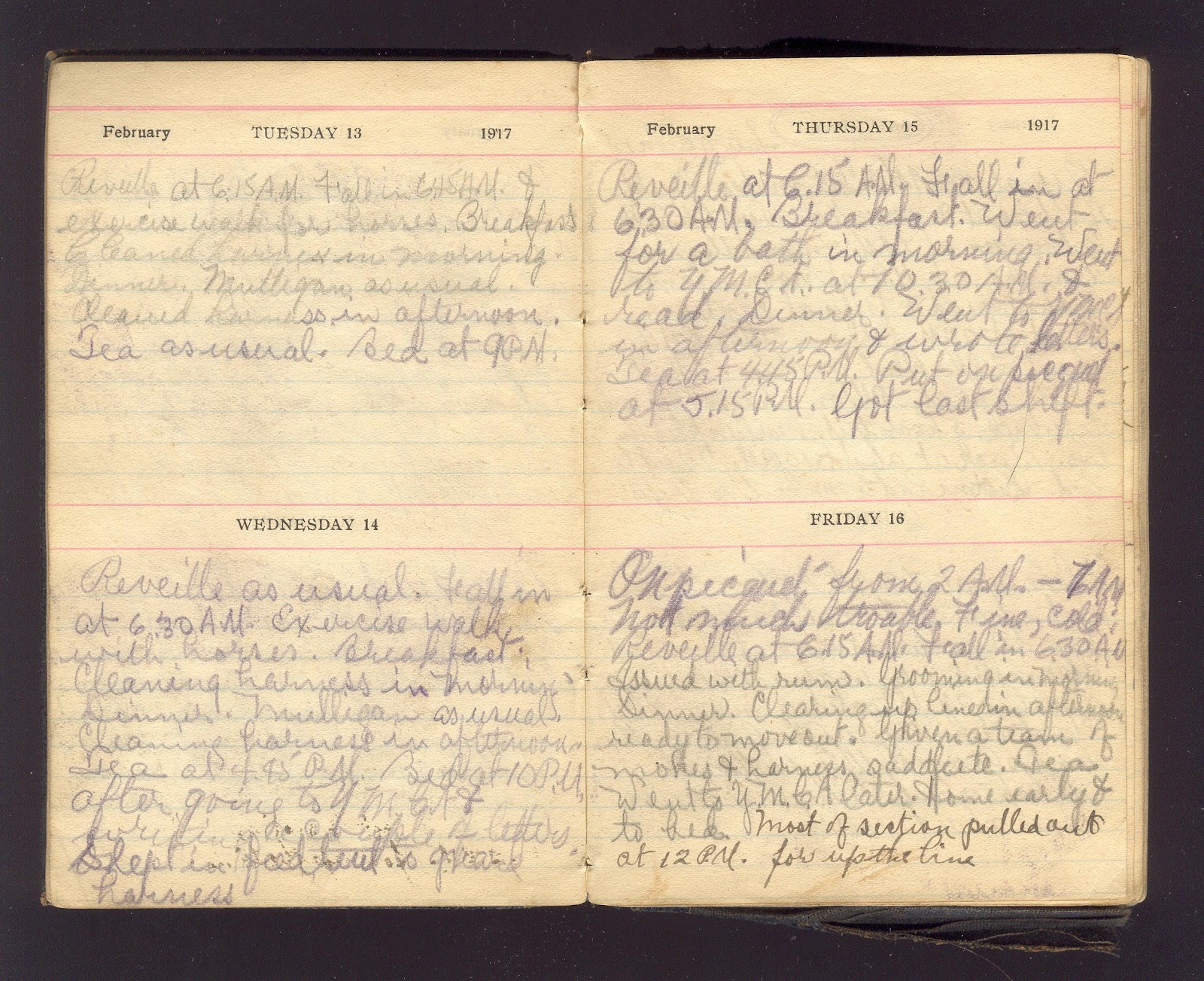

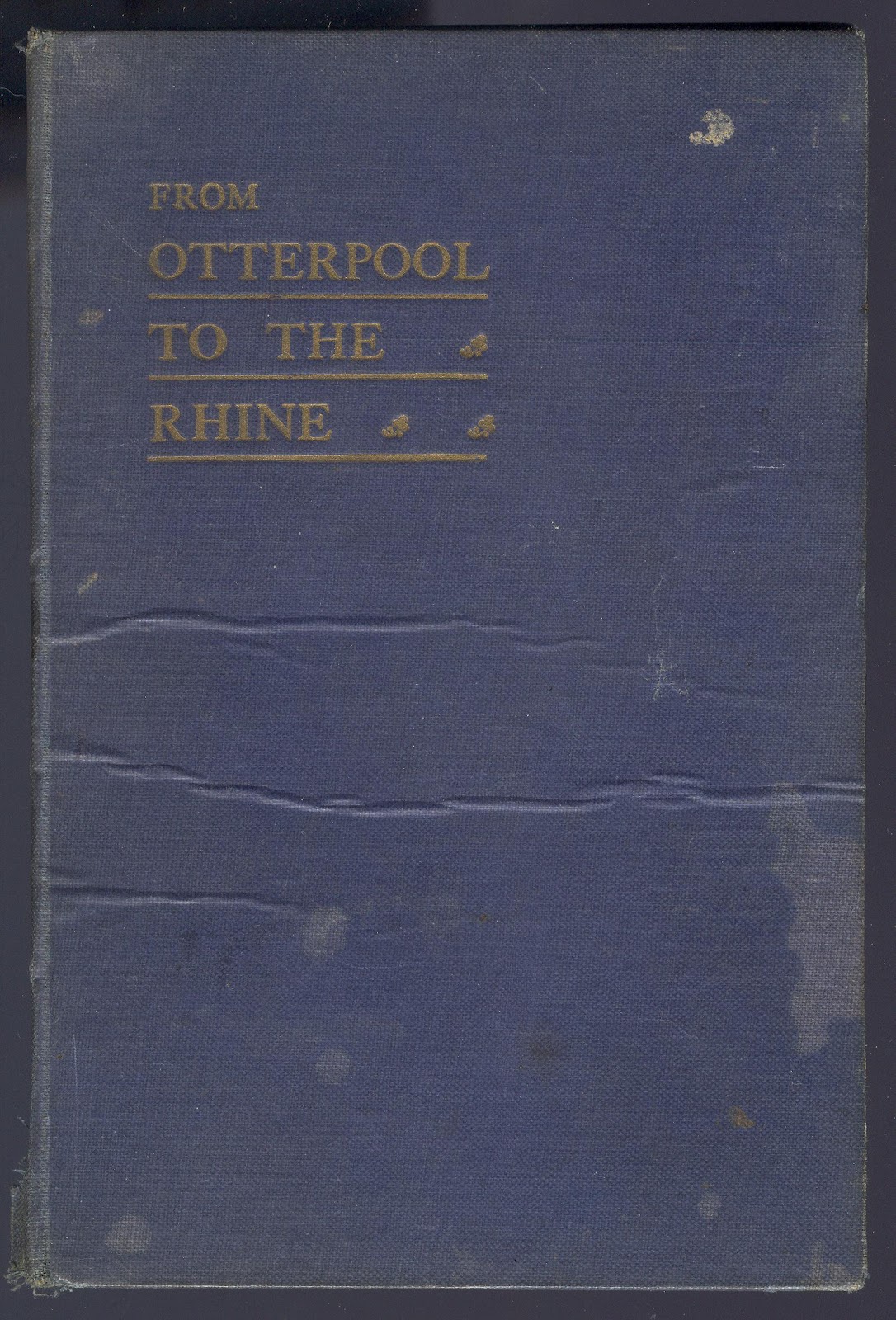

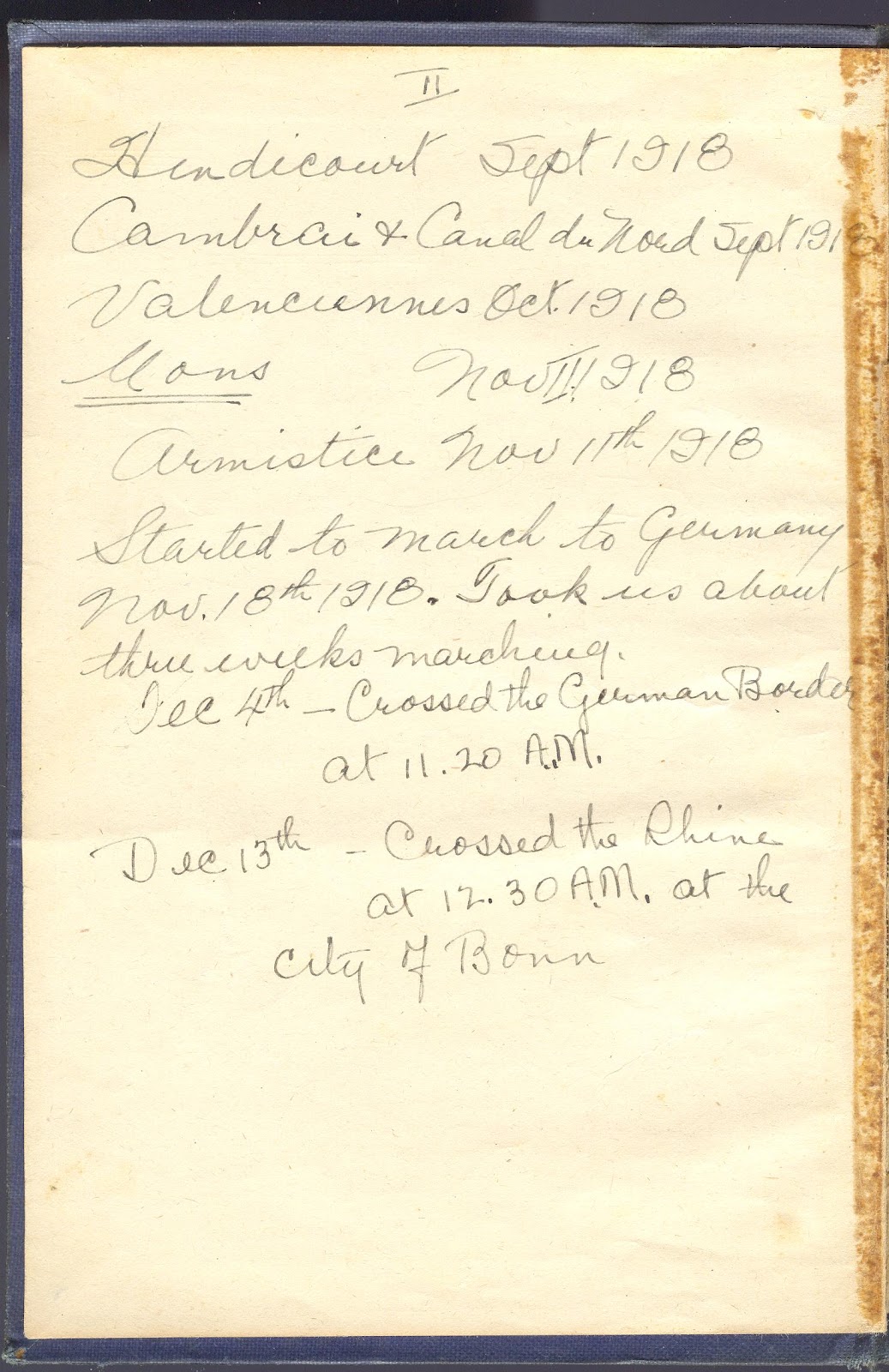

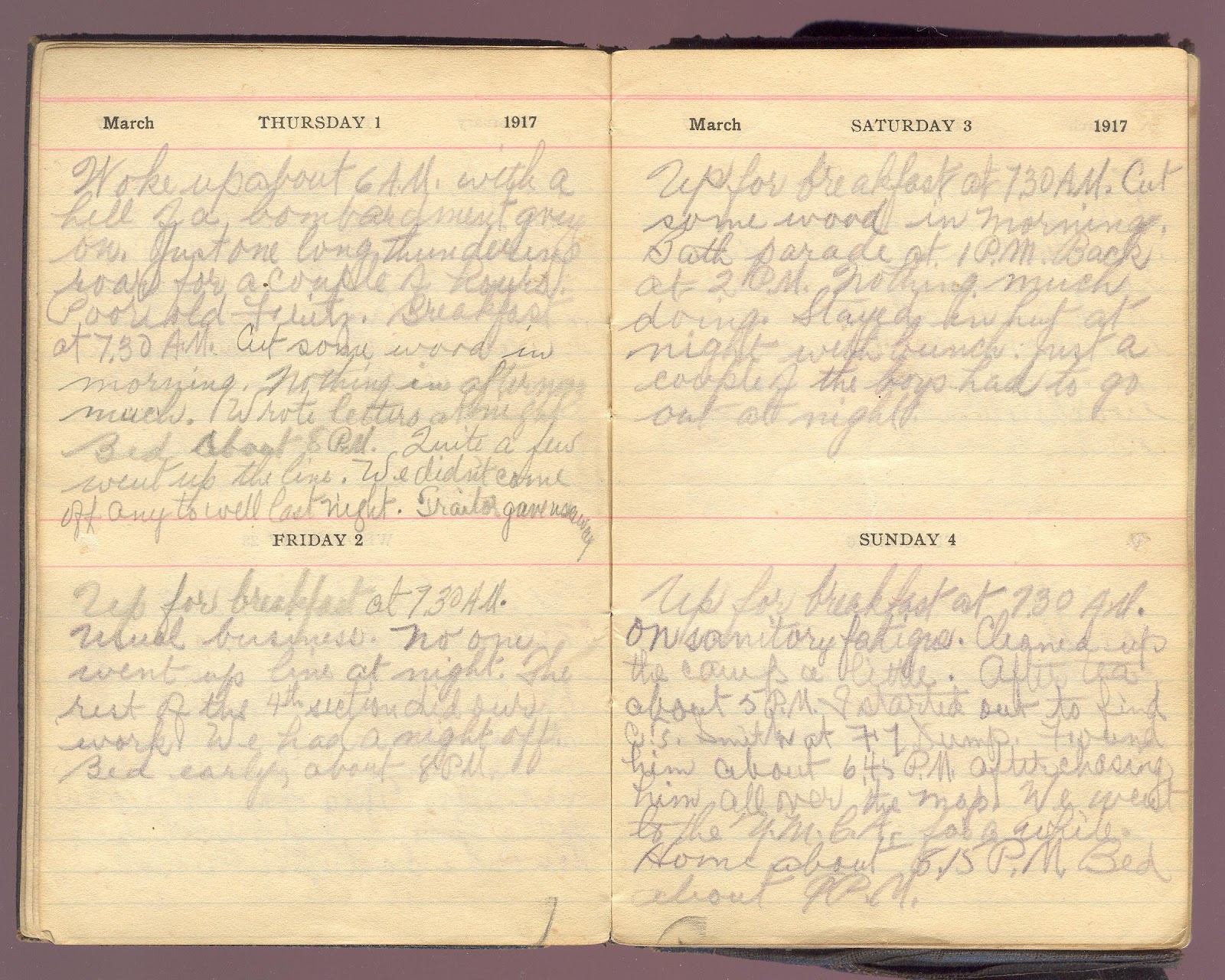

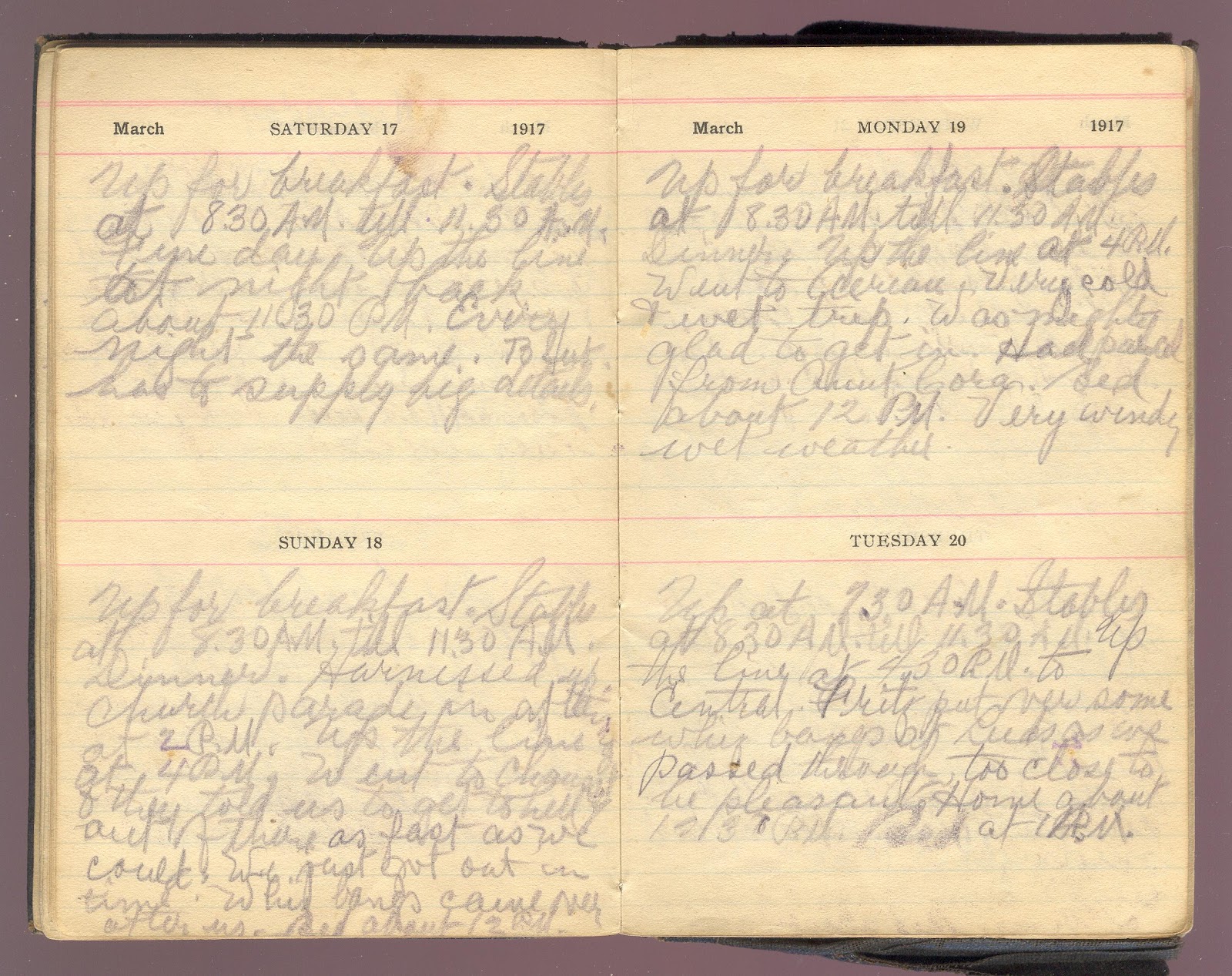

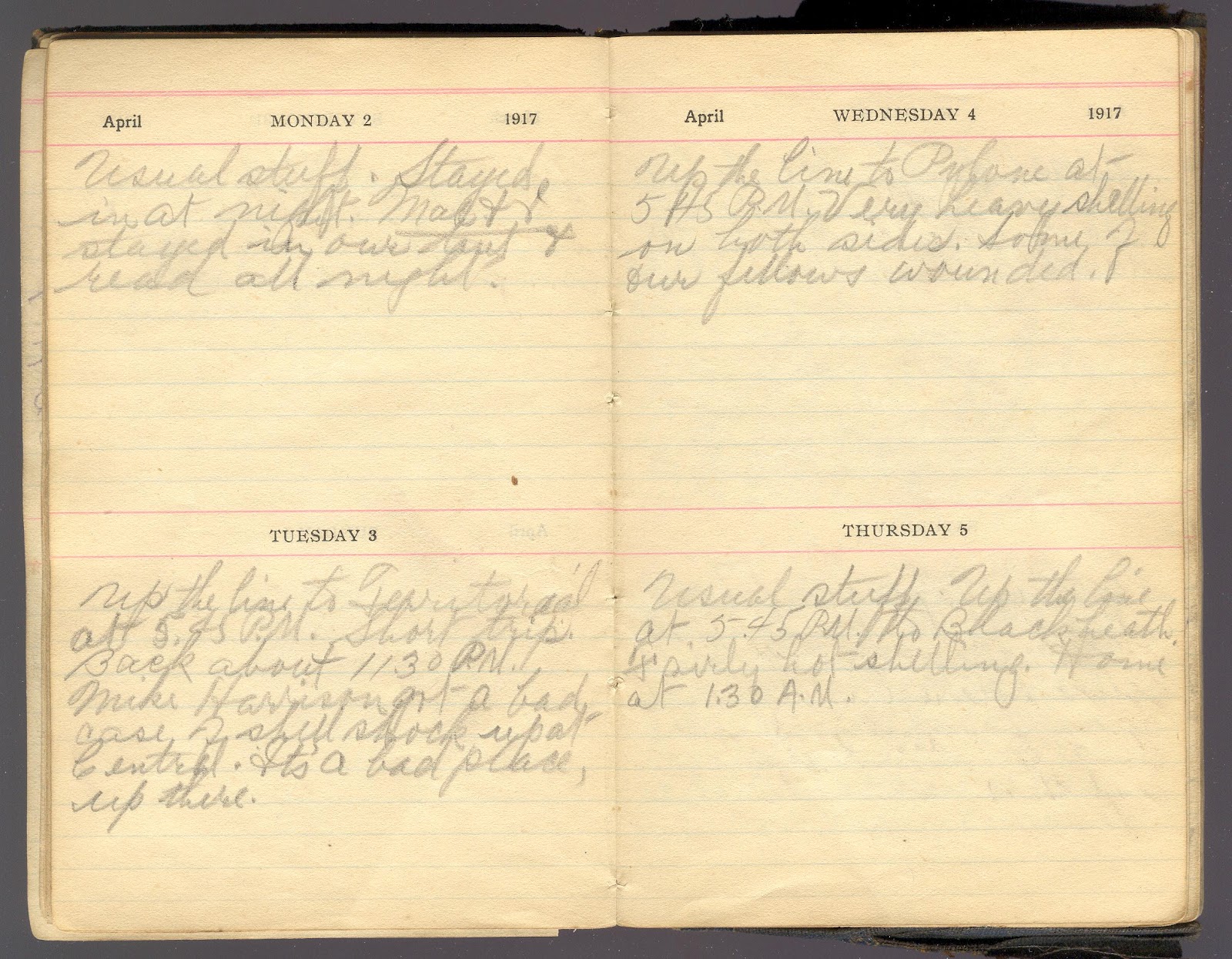

Reginald Mulkins' WWI Diary

A Personal Chronicle of the Great War

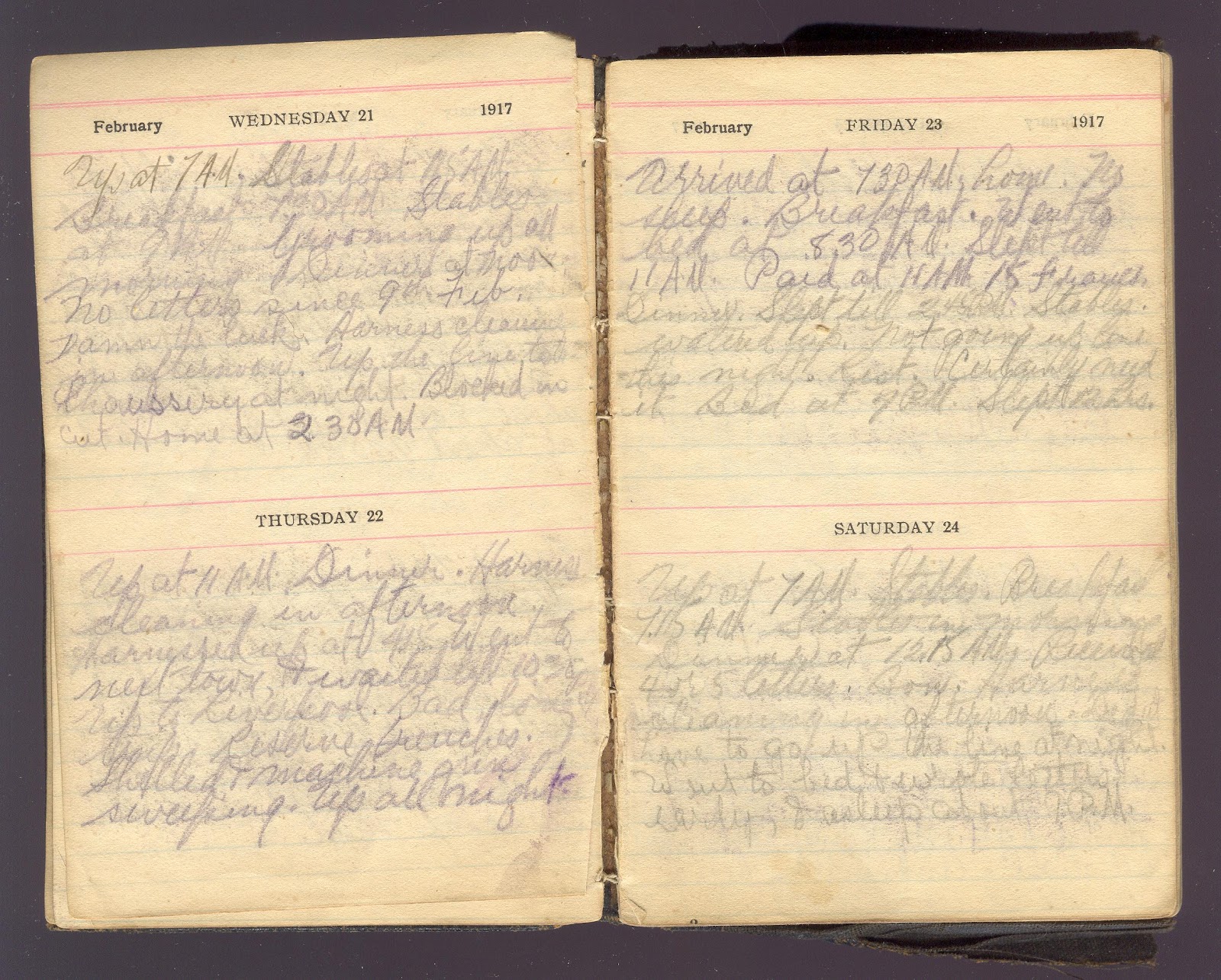

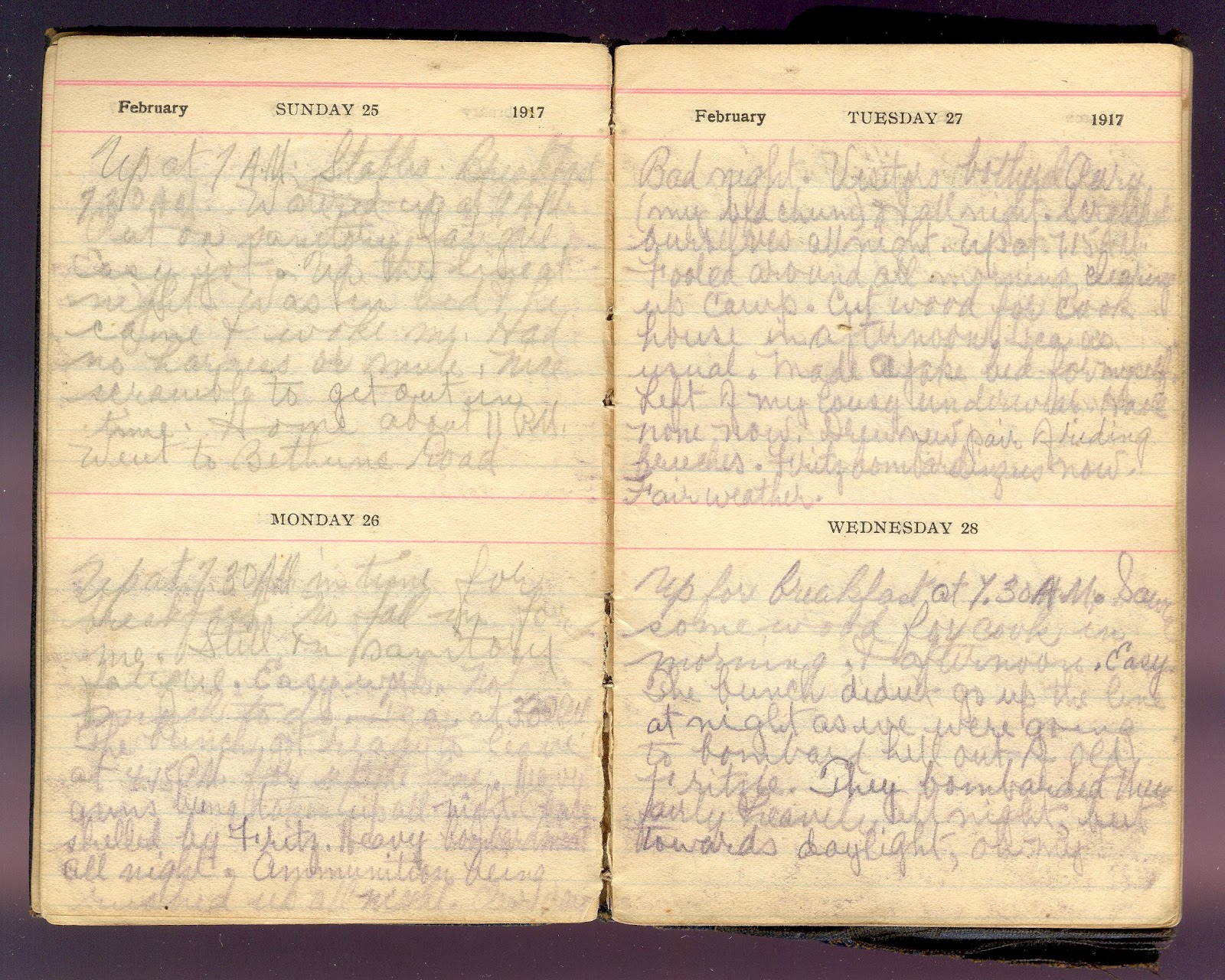

Diary Pages Preserved

41 Pages

Time Period Covered

March - April 1917

Historic Battle

Vimy Ridge

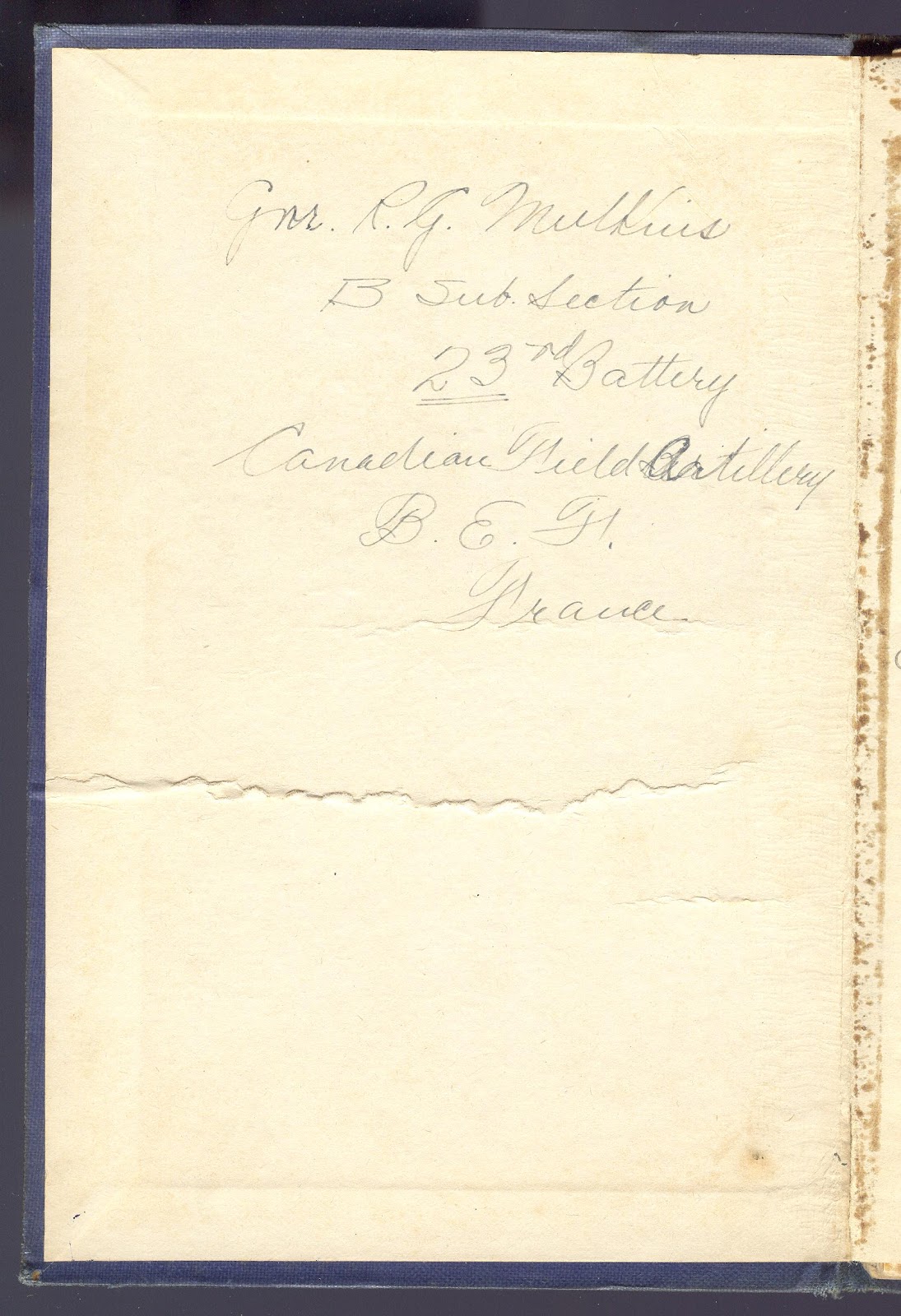

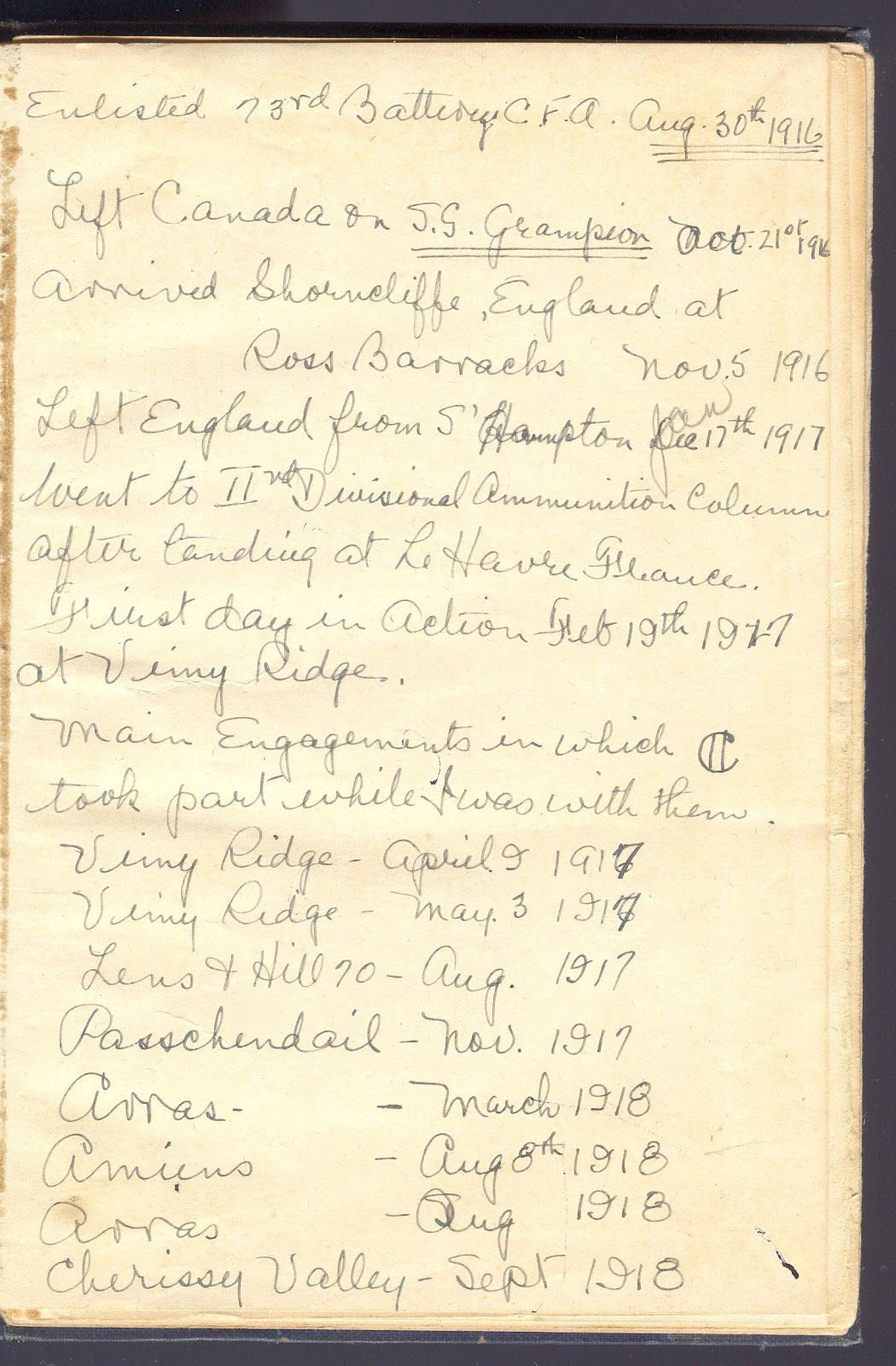

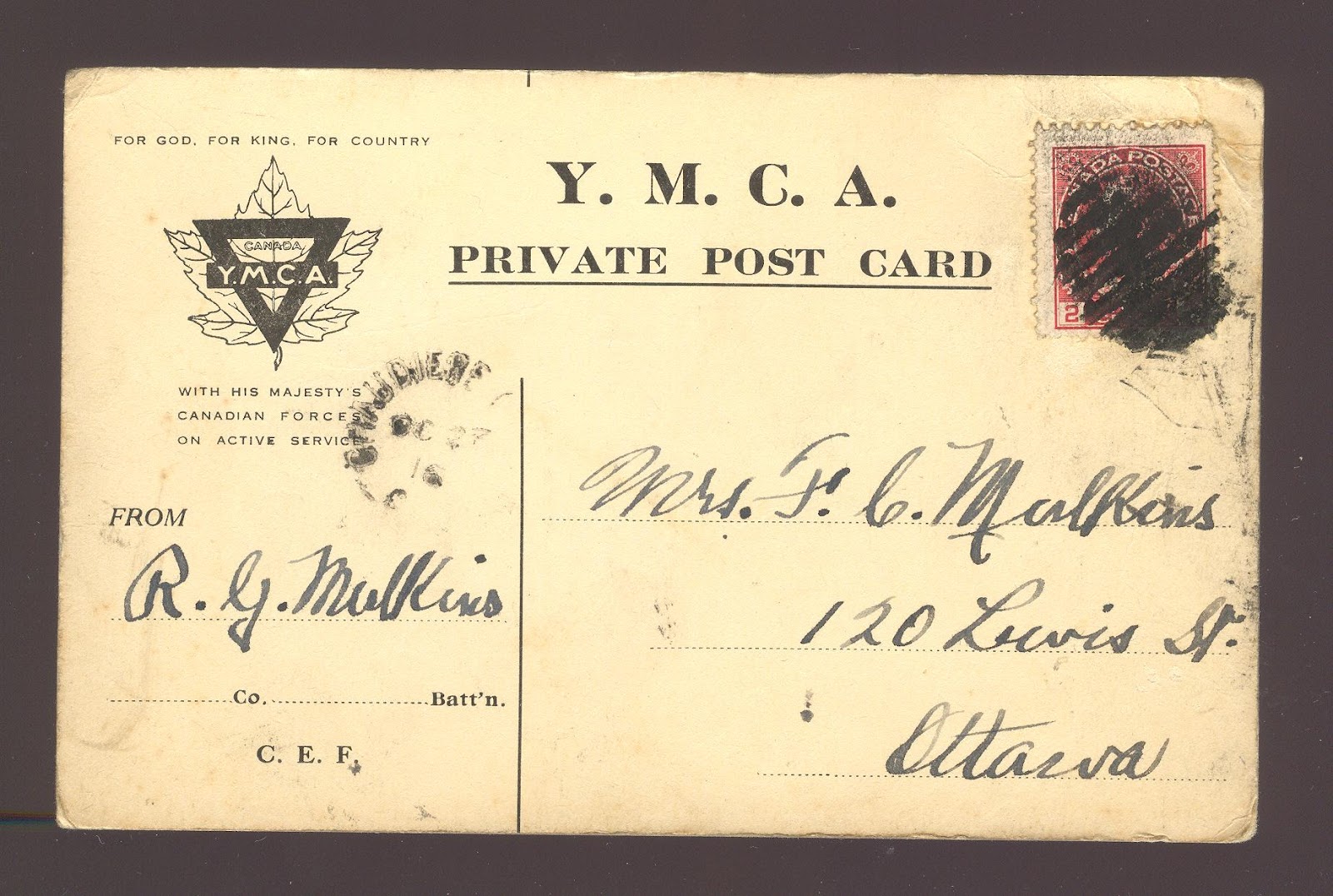

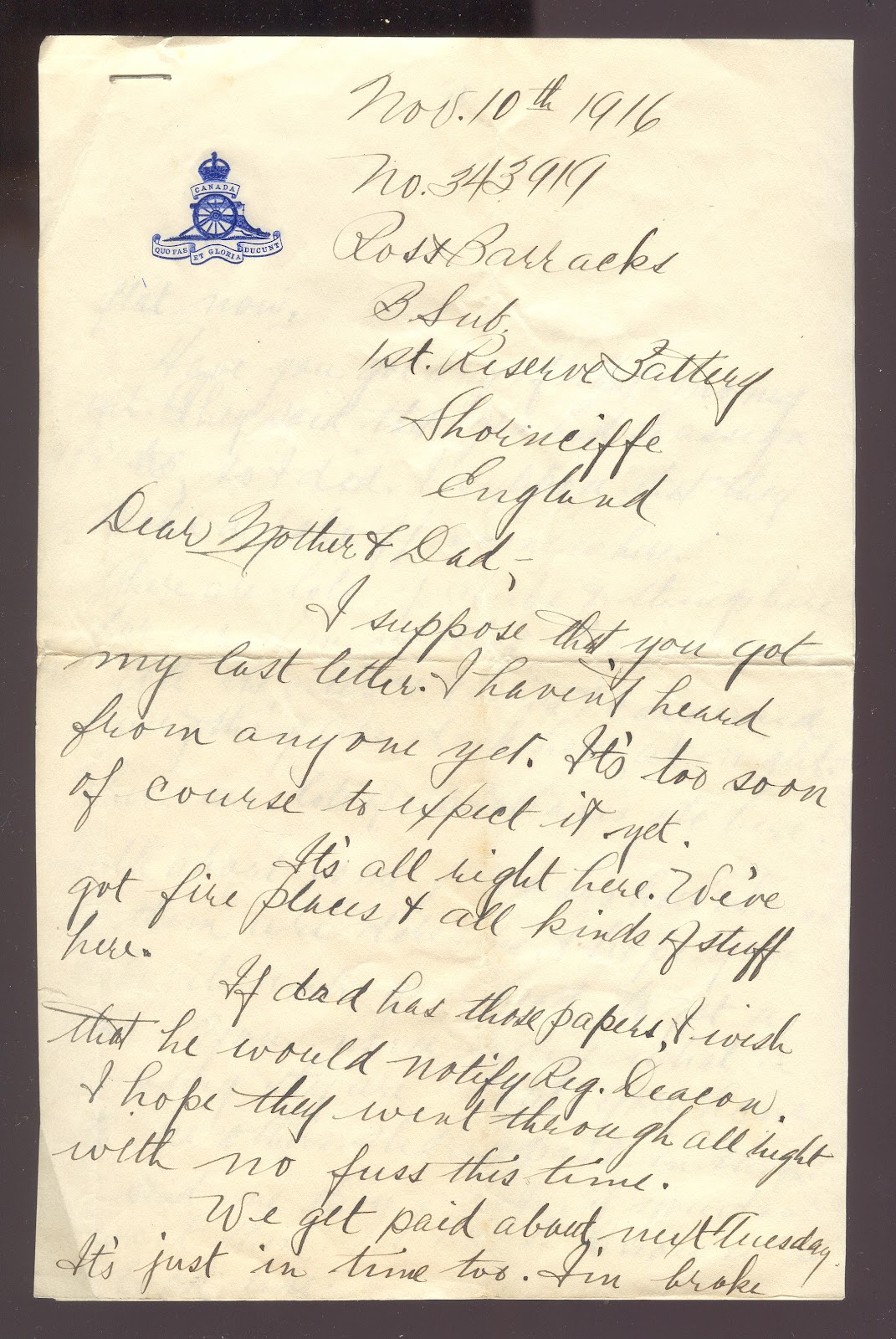

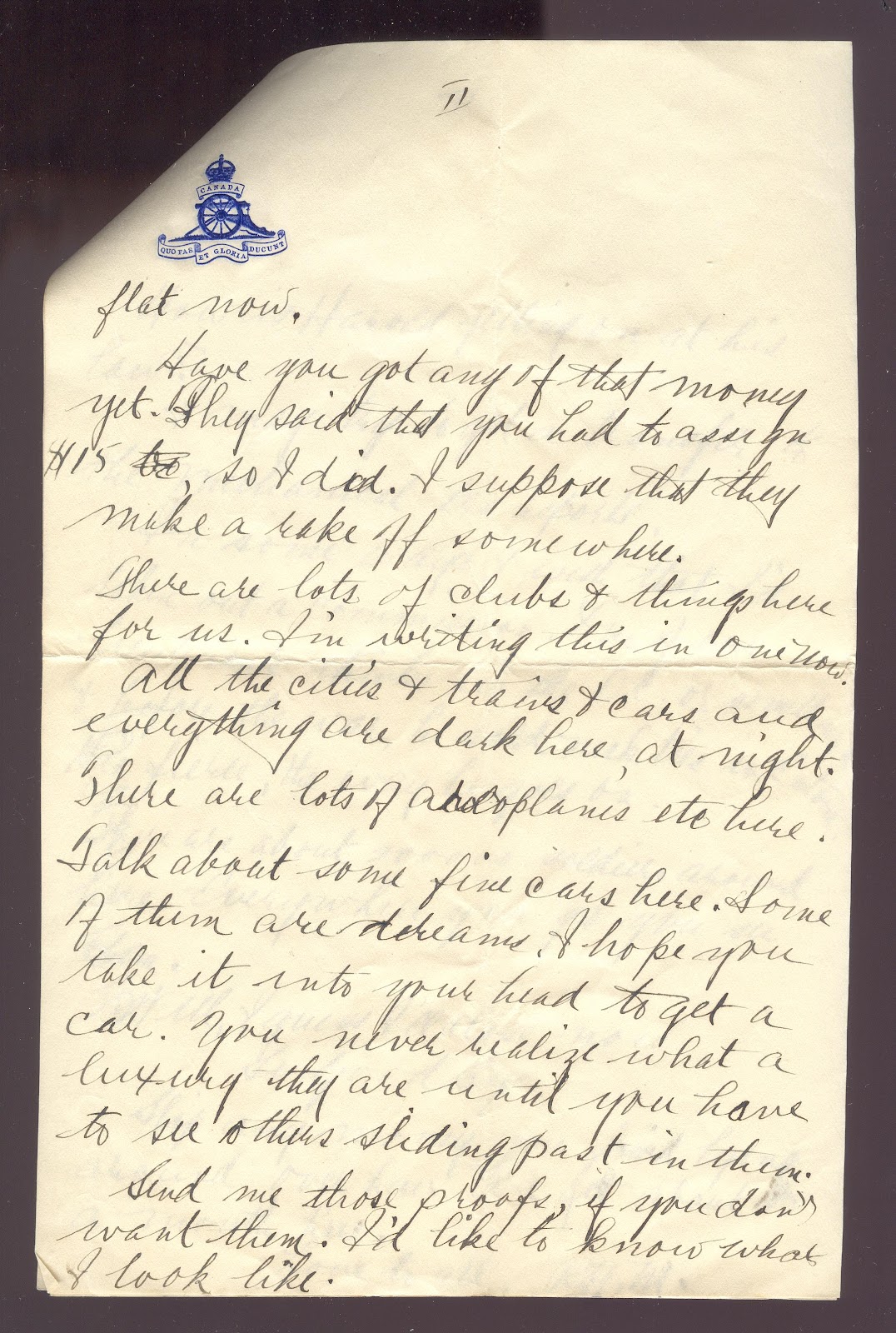

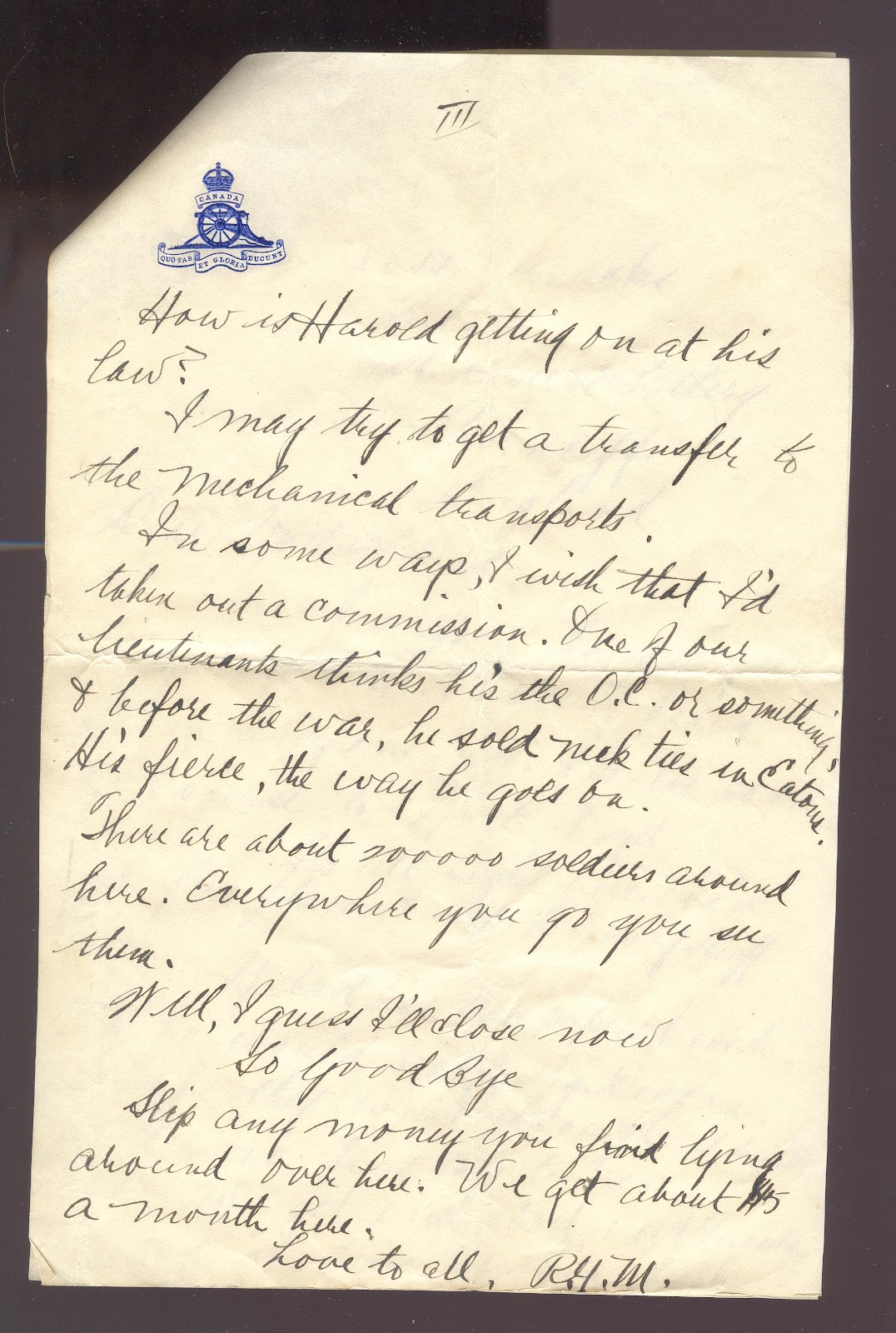

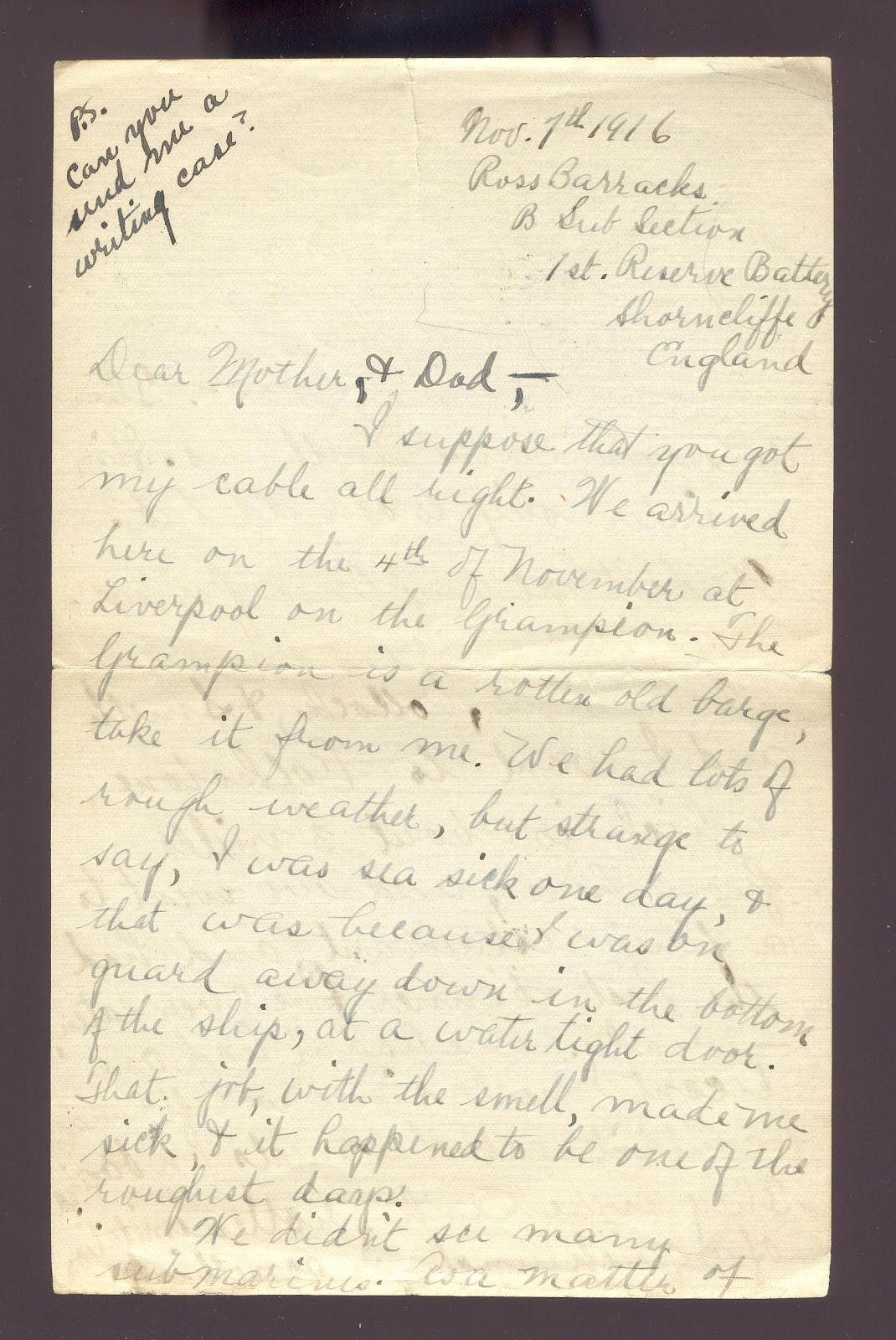

The Boy Who Became a Soldier

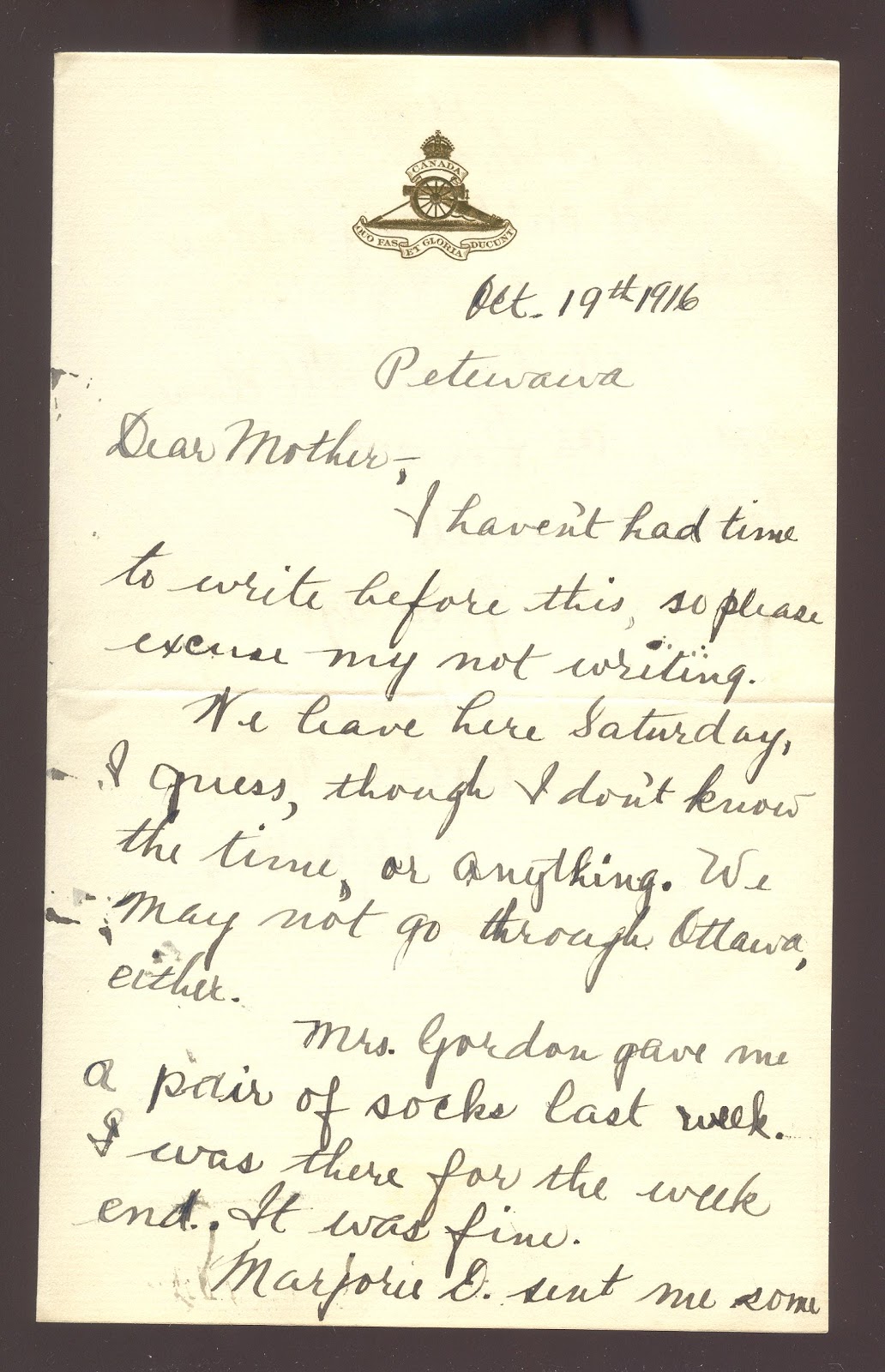

In the twilight of his childhood, Reginald Mulkins made a choice that would forever alter the trajectory of his life. At sixteen, with the world embroiled in a conflict of unprecedented scale, he stood before the recruitment officer and added years to his age with a steady hand and a resolute heart. He was not alone in this deception—approximately 20,000 underage Canadians would follow the same path, driven by a complex tapestry of patriotism, economic necessity, and the irresistible call of adventure that war, in its cruel irony, often presents to the young.

The promise of $1.10 per day was a fortune to a teenager in 1916, enough to send home to a family struggling in the wartime economy. But it was more than money that drew Reginald to the colors. It was the siren song of purpose, of belonging to something greater than oneself, of testing one's mettle in the crucible of history. Like so many of his generation, he could not know that the mettle he sought to test would be forged in fire and tempered by loss.

In memory of our great-grandfather, whose courage and sacrifice continue to resonate through the generations of our family

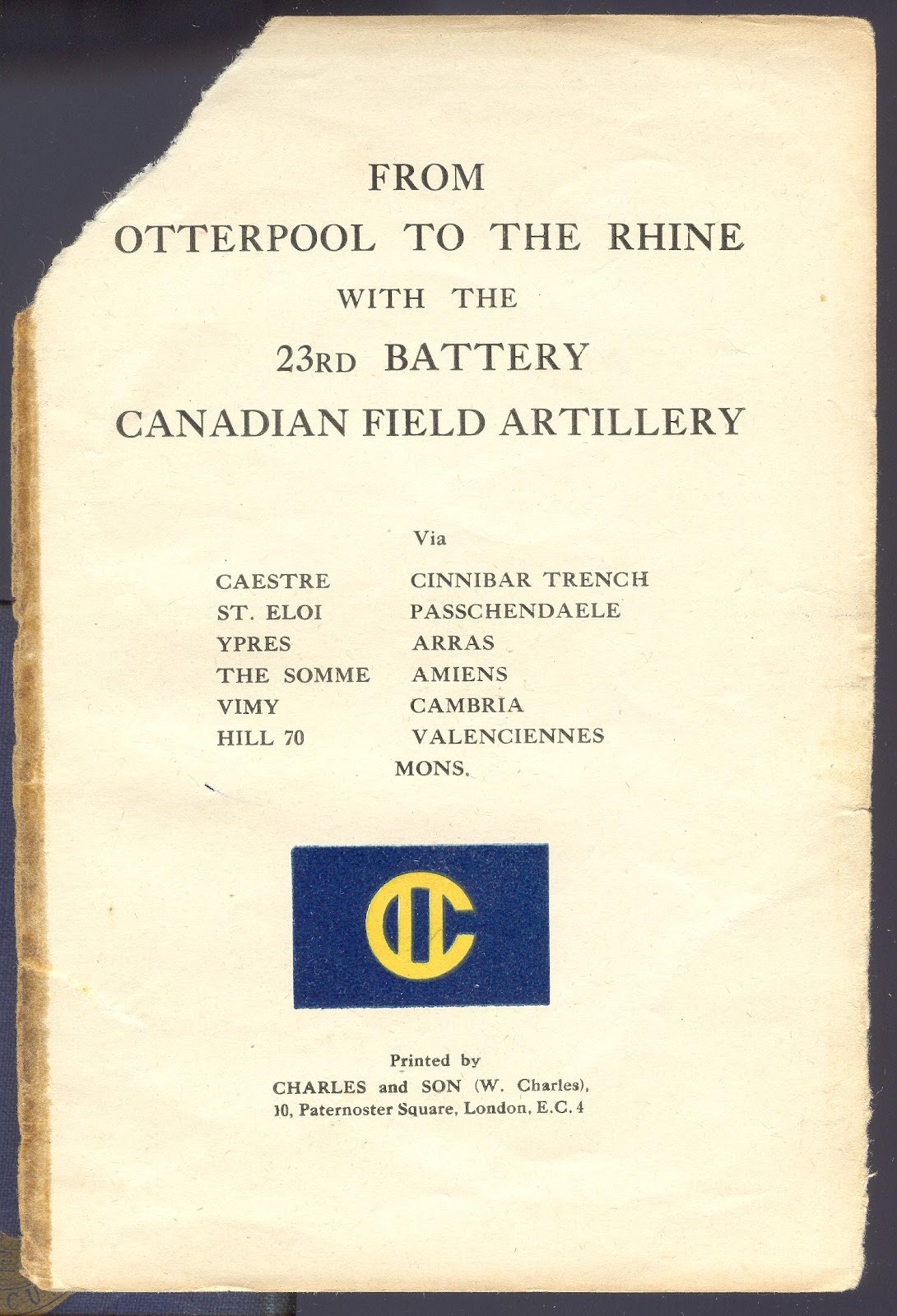

The Unsung Heroes of the Supply Lines

While history remembers the infantrymen who stormed the trenches and the pilots who danced in the clouds, it often forgets the men like Reginald Mulkins—the mule skinners who formed the vital circulatory system of the Allied war machine. As a mule skinner, or ammunition runner, Reginald operated in one of the most dangerous and thankless roles of the war, far from the glory of the front line yet essential to its function.

The Mule Skinner's Burden

Mule handlers faced casualty rates of 30-40% during major offensives, their work taking them through the most perilous territory between the front lines and artillery positions. Each night, teams moved over a thousand artillery shells through treacherous landscapes of mud, wire, and shell craters, often under direct enemy fire. The mules themselves became both companions and unwitting heroes, their instincts often proving more reliable than human judgment in the chaos of the battlefield.

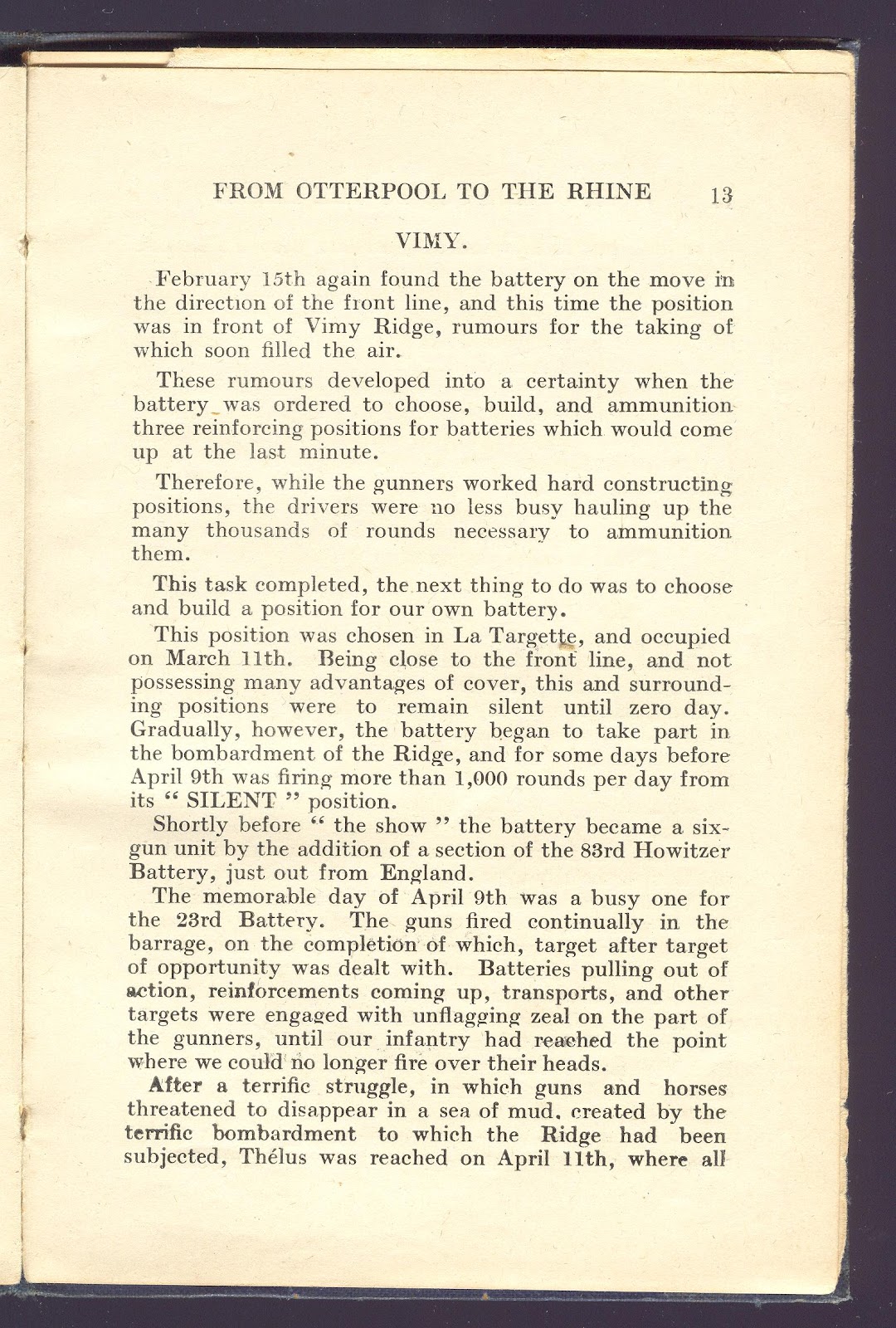

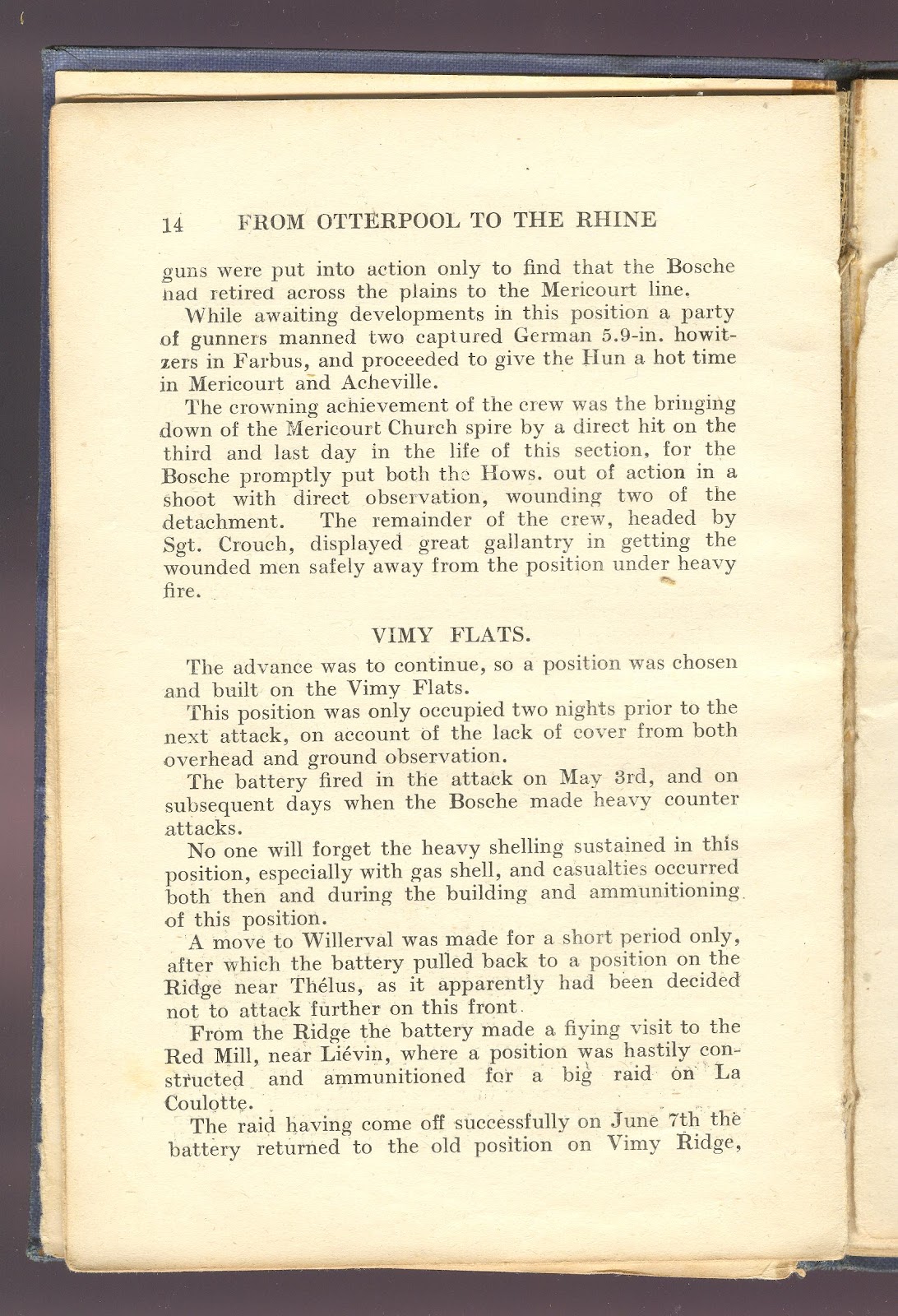

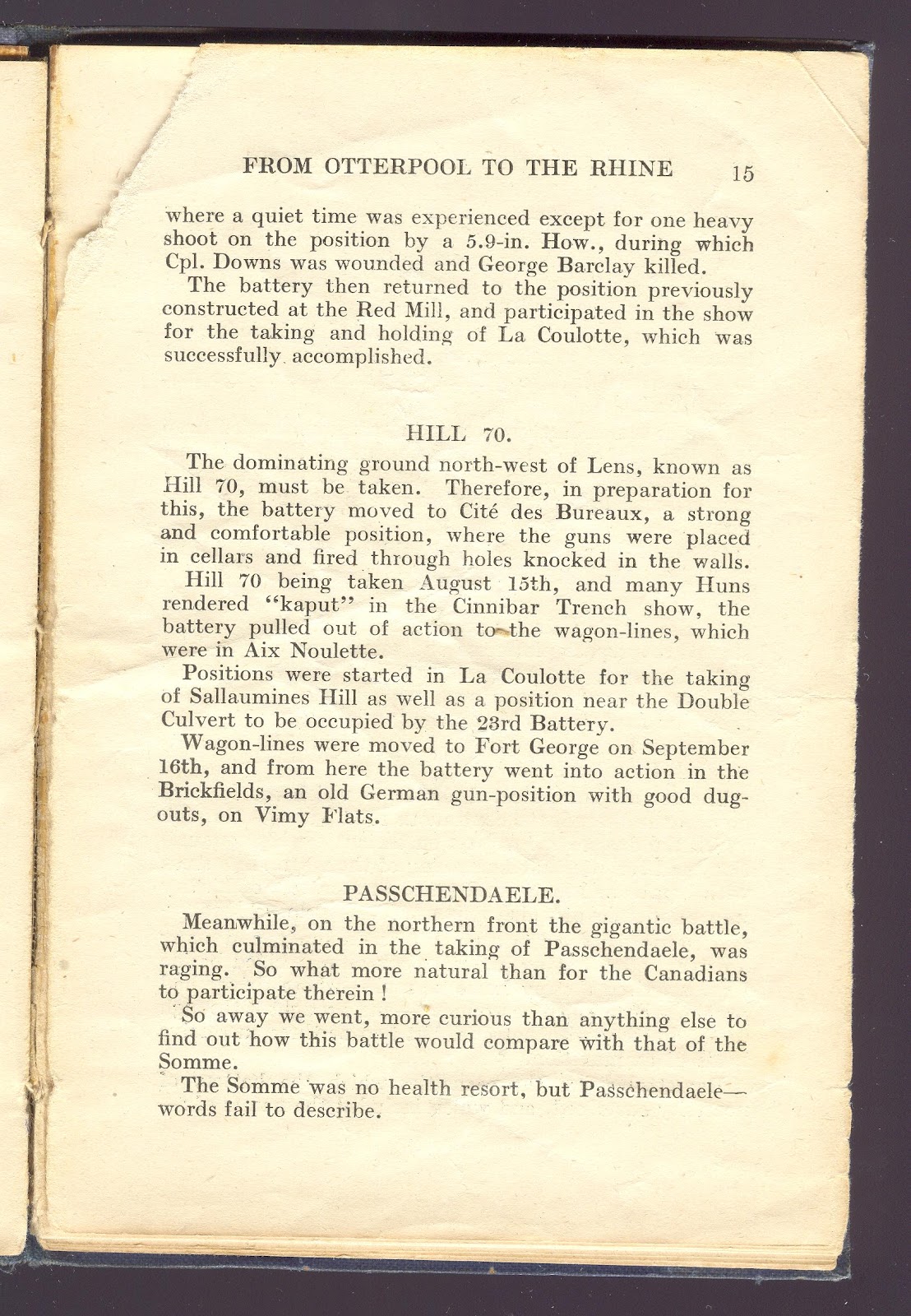

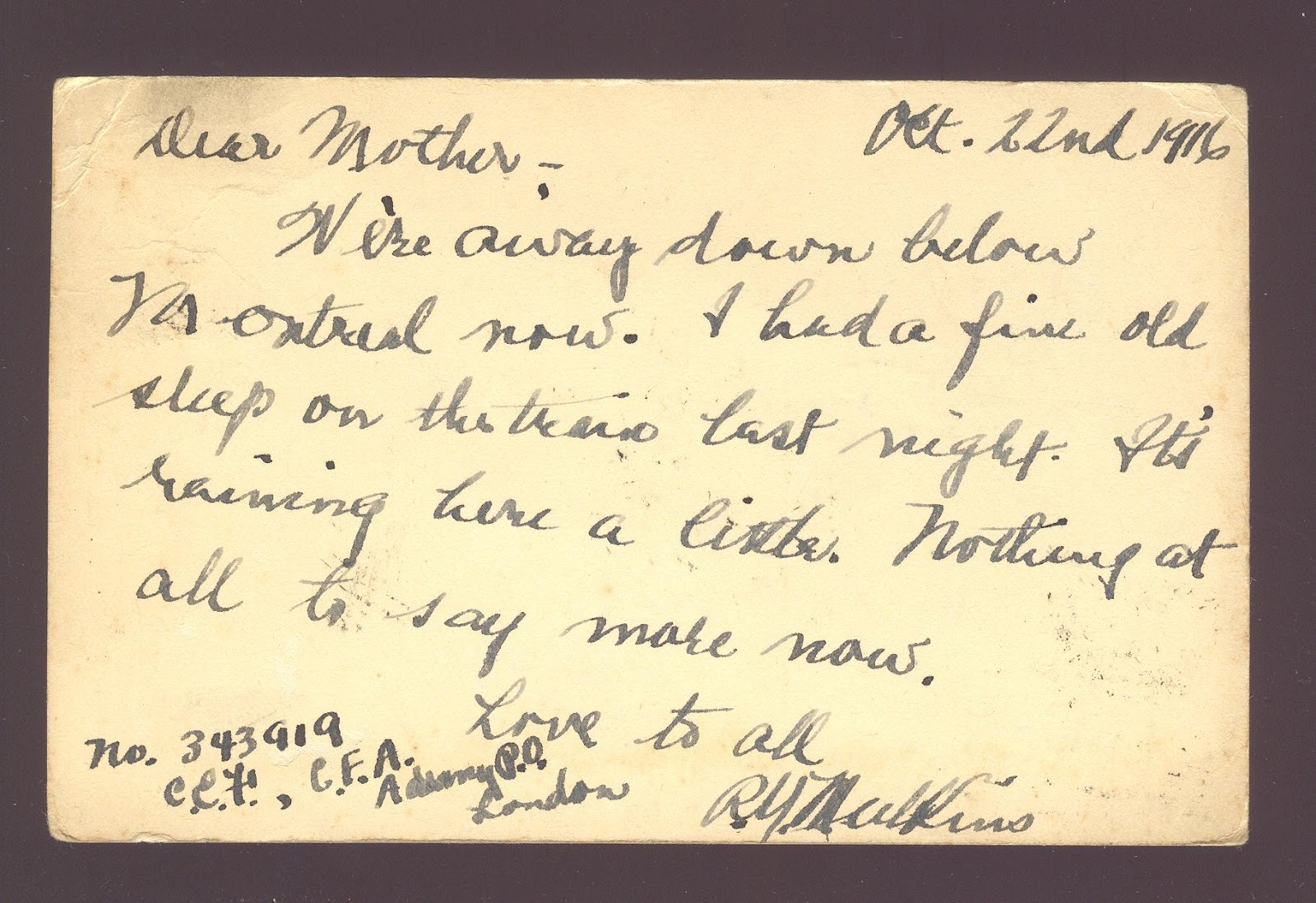

Vimy Ridge: The Crucible of Nations

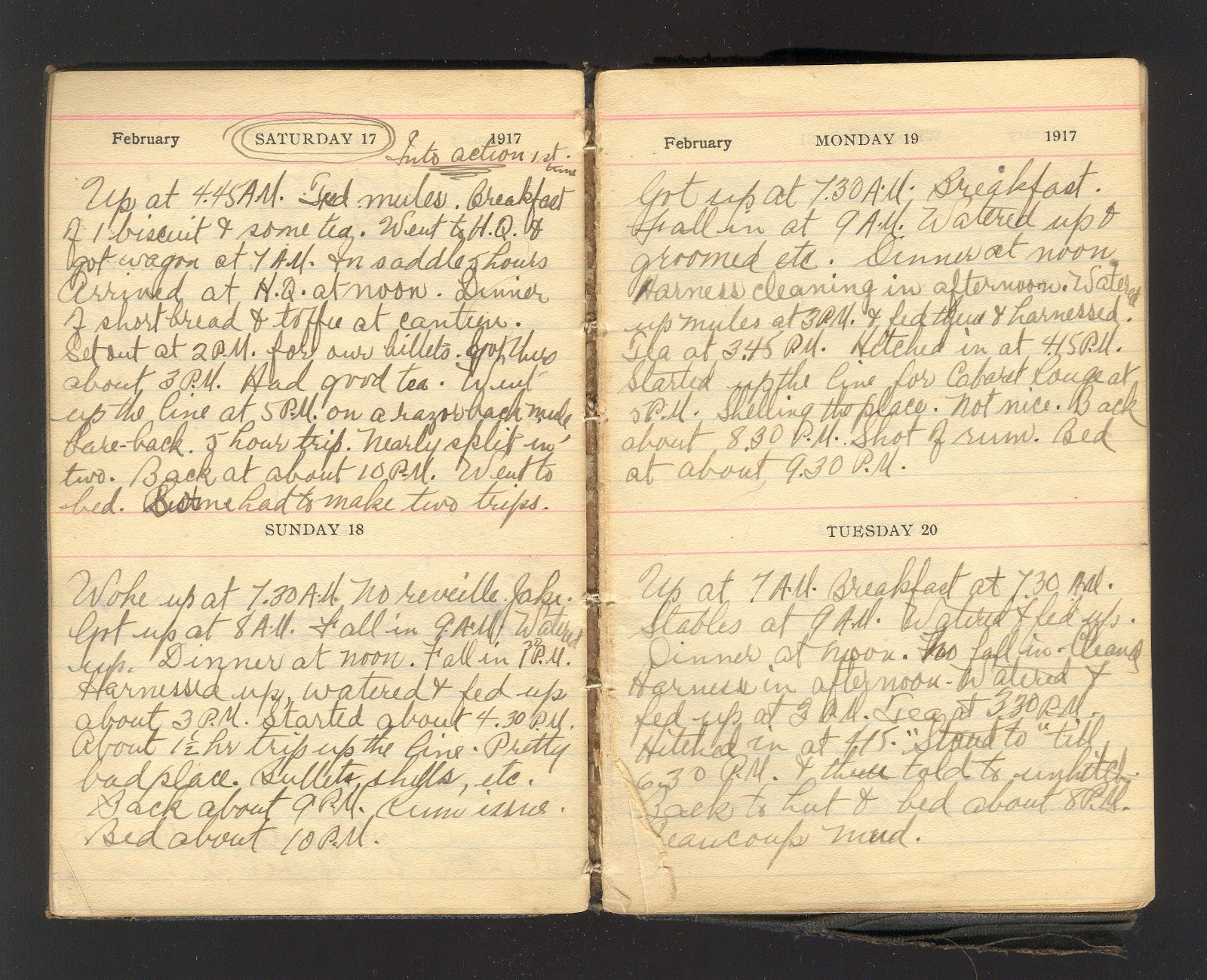

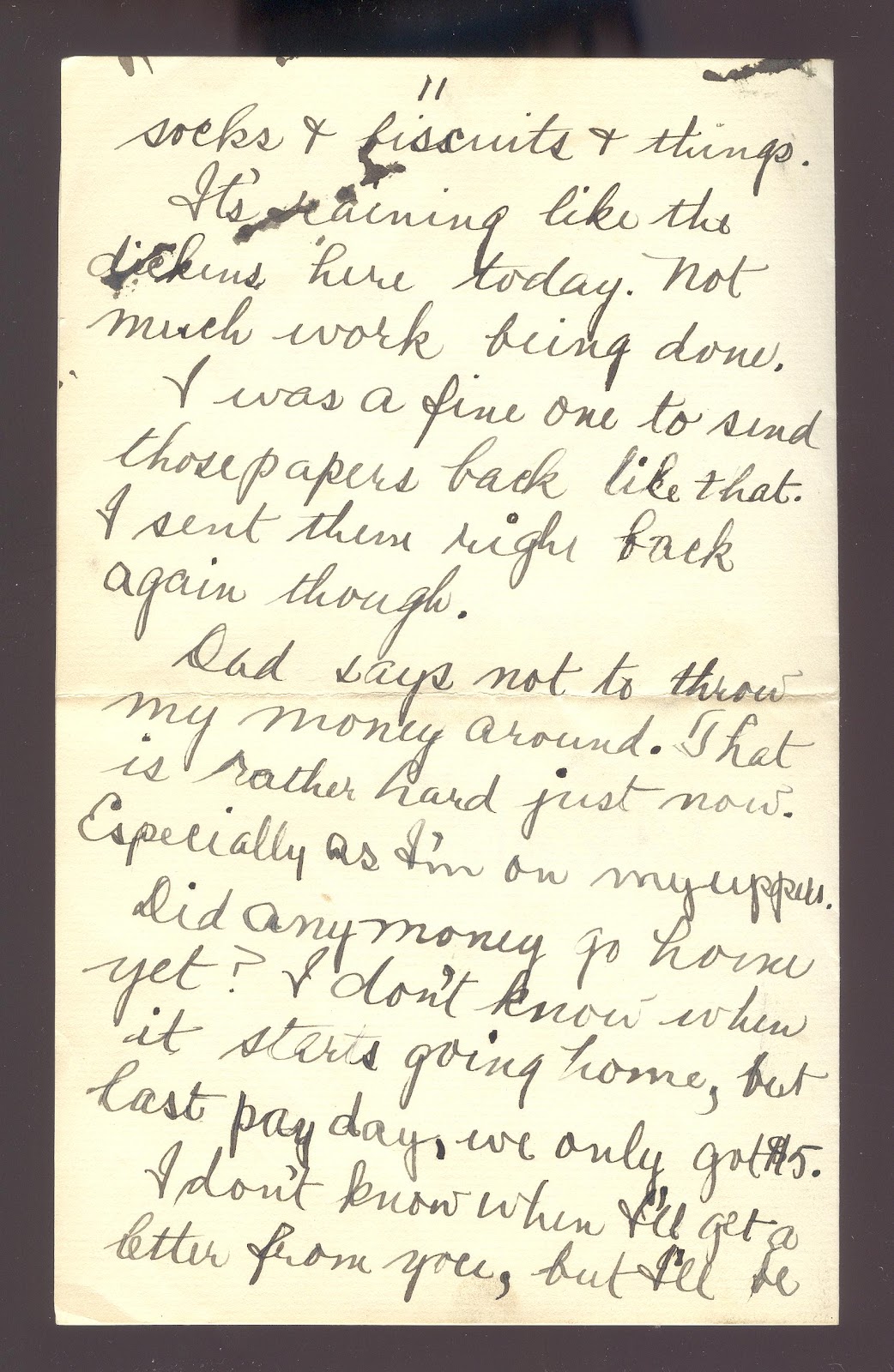

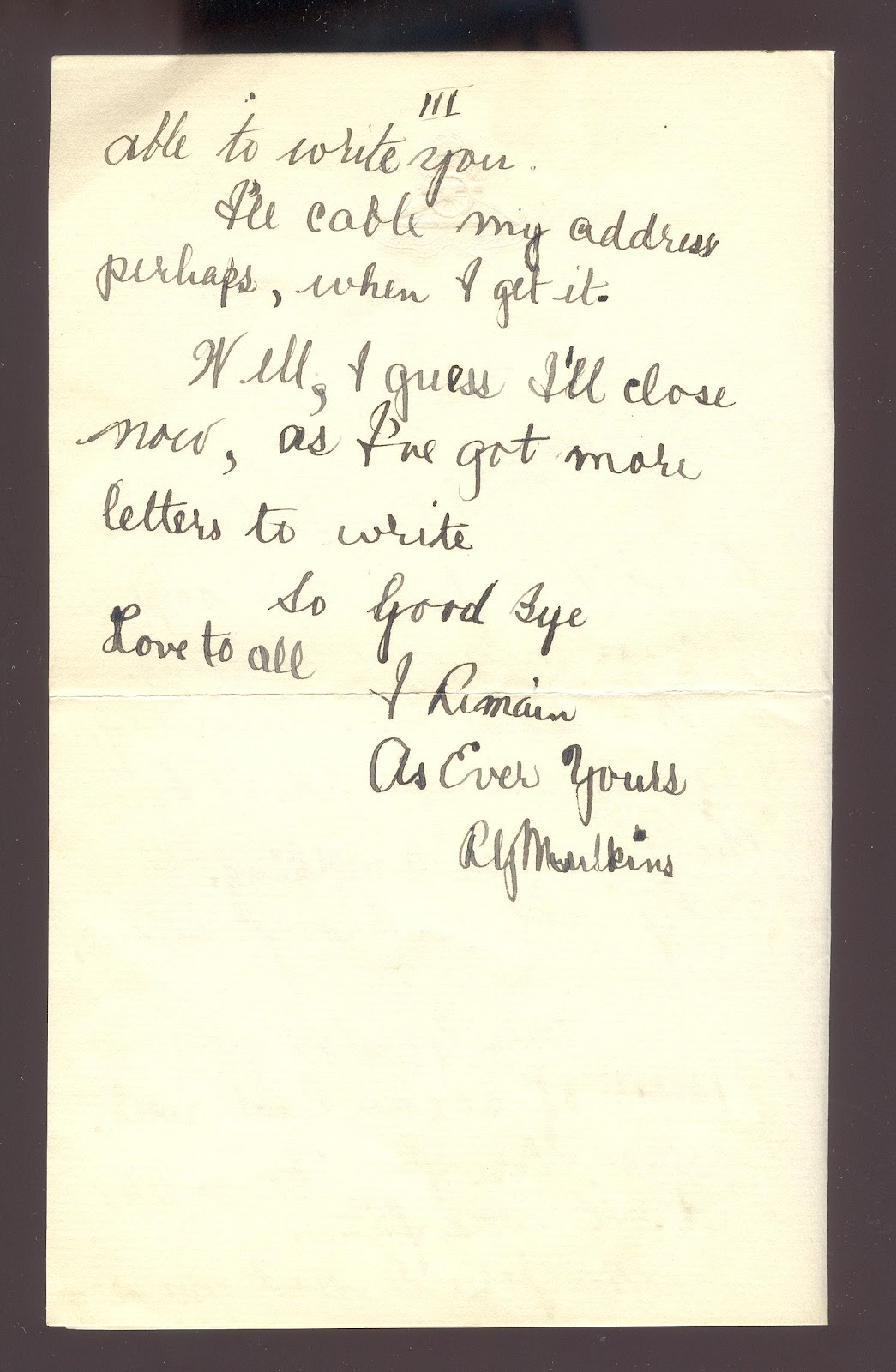

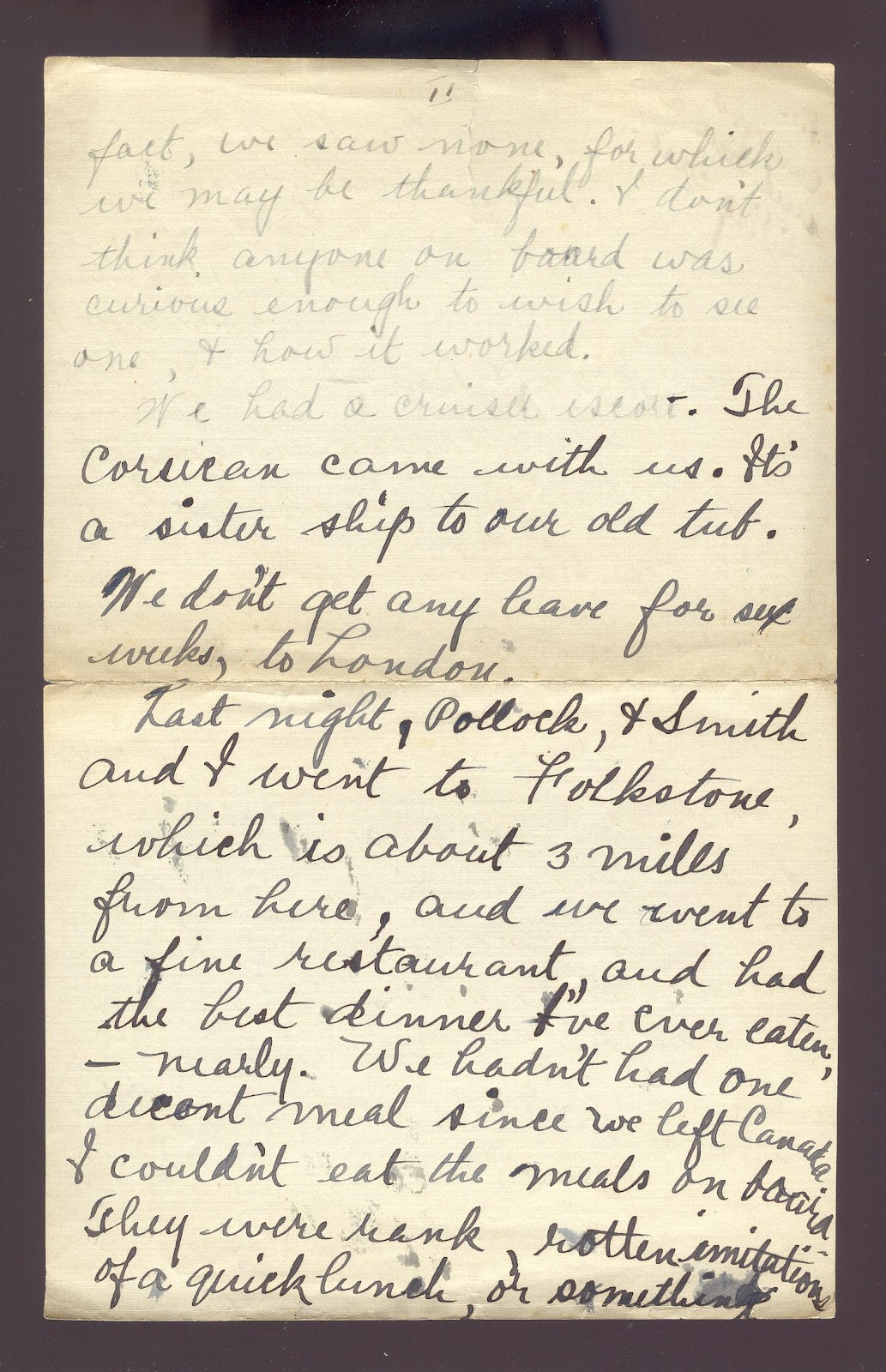

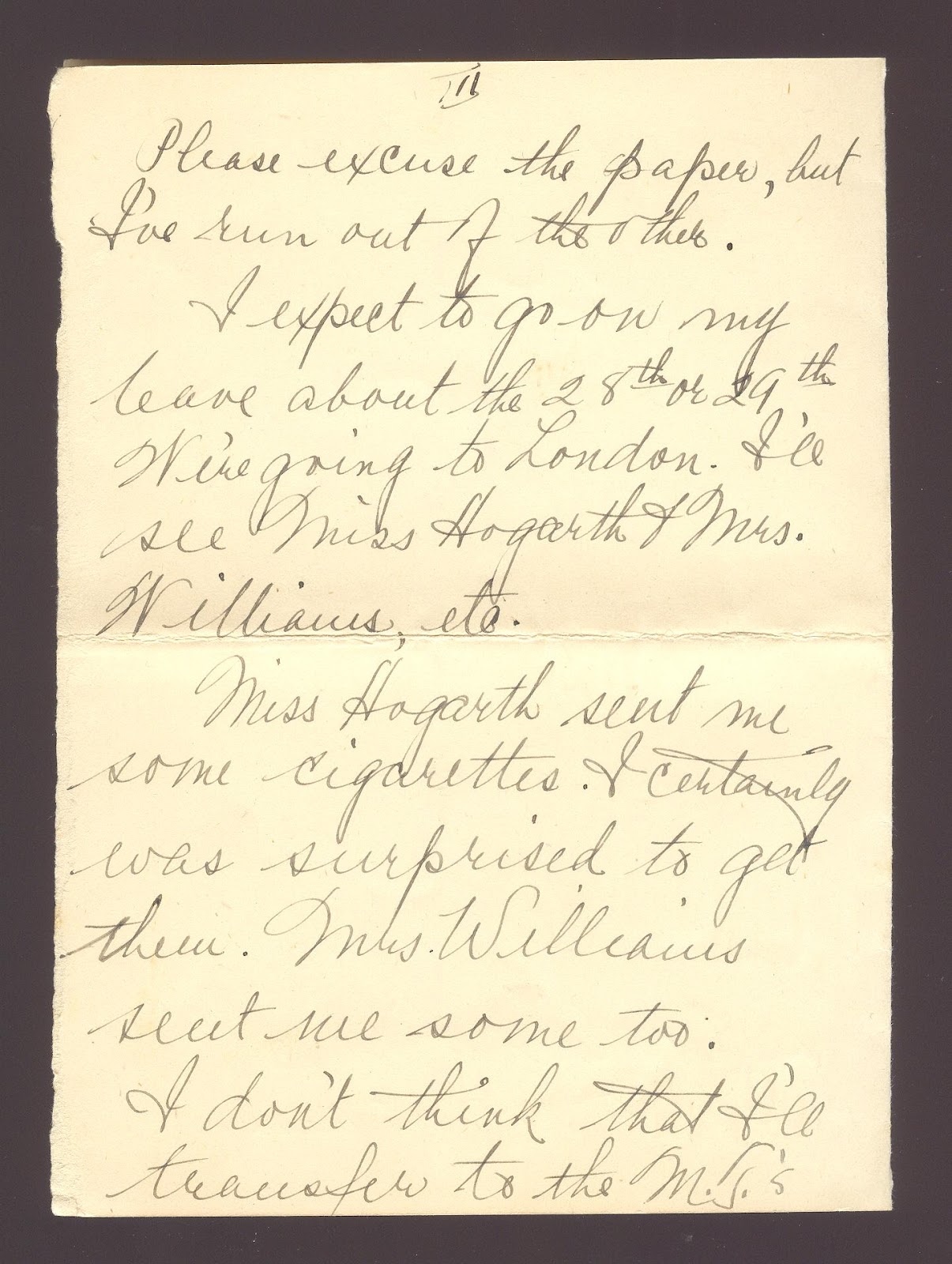

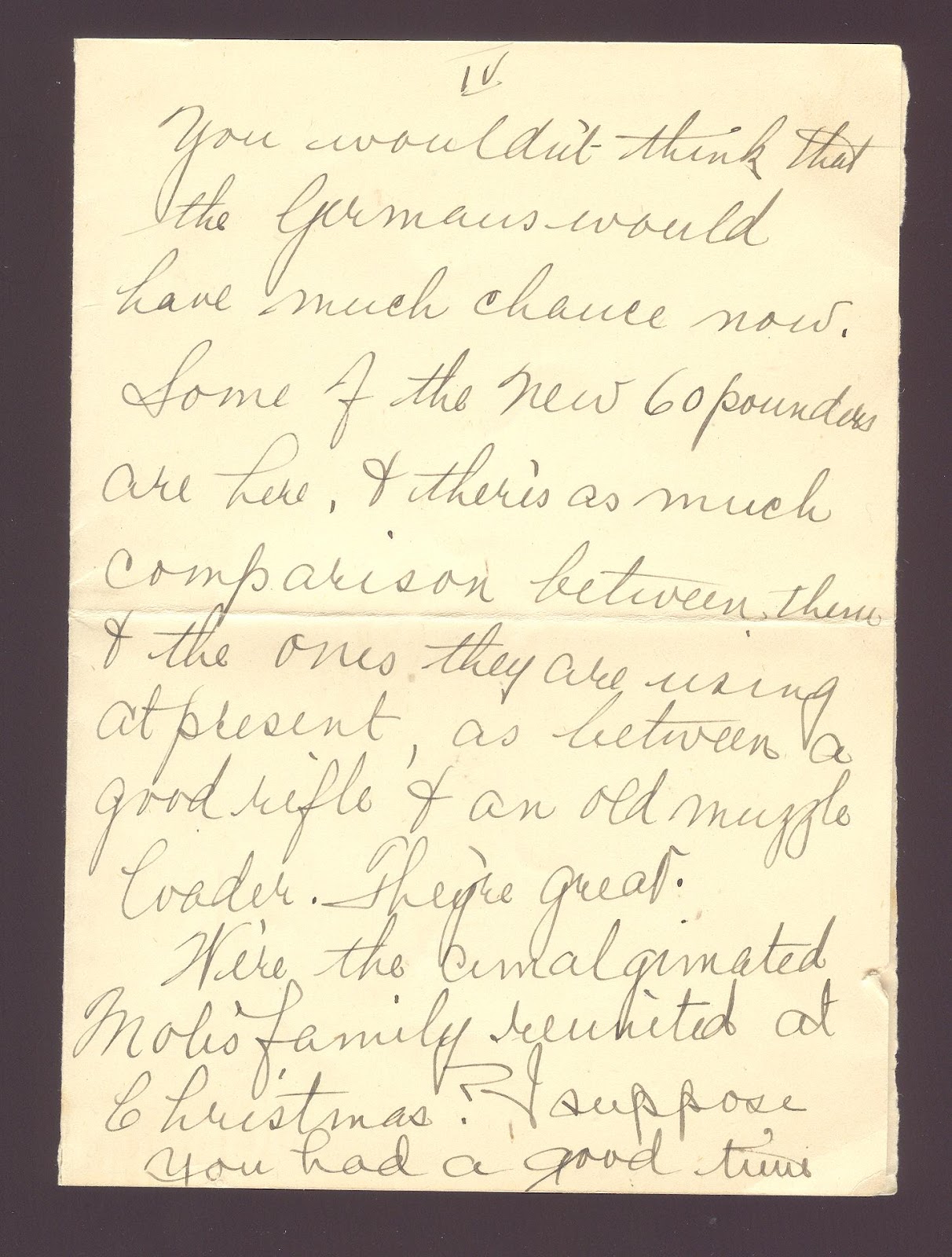

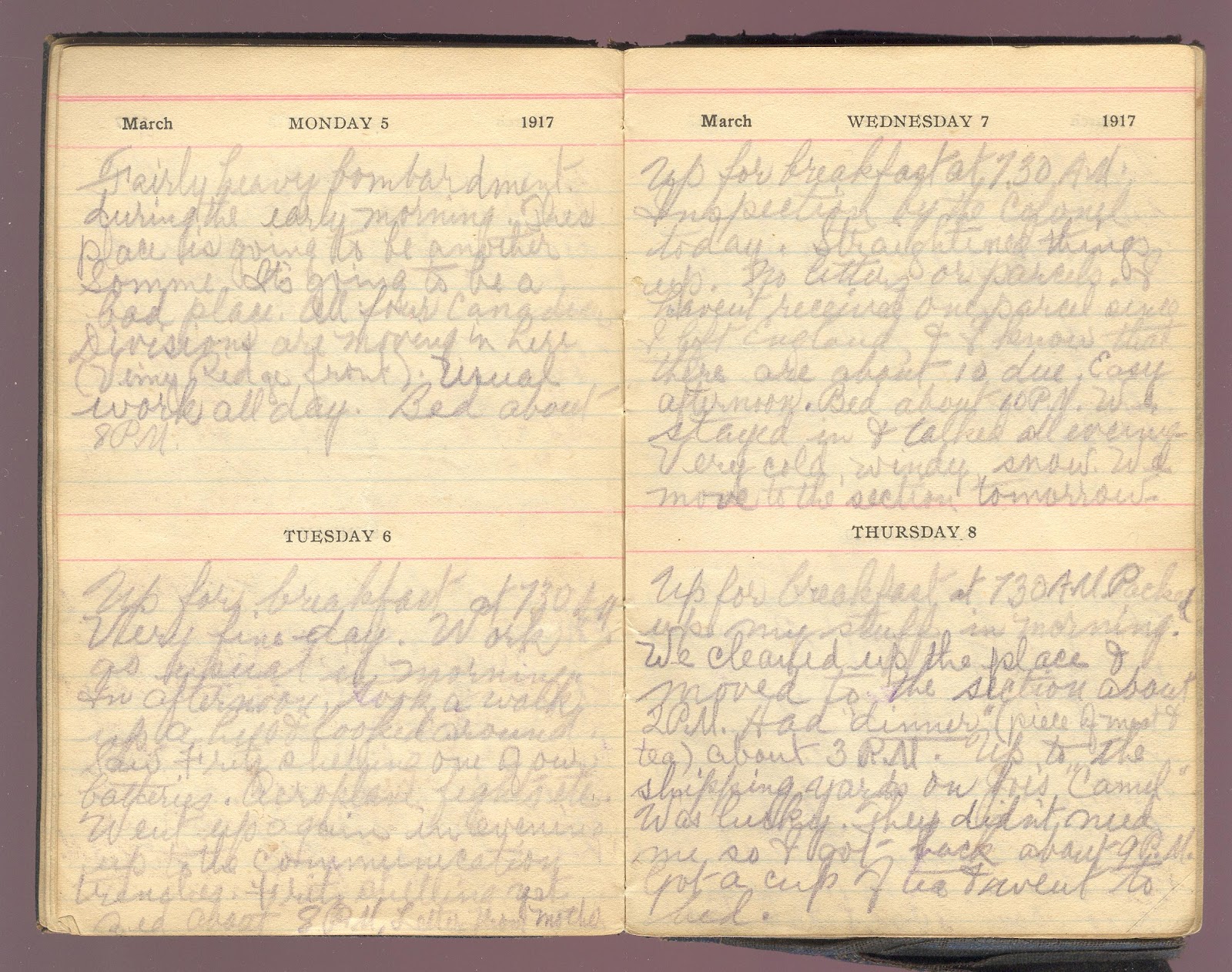

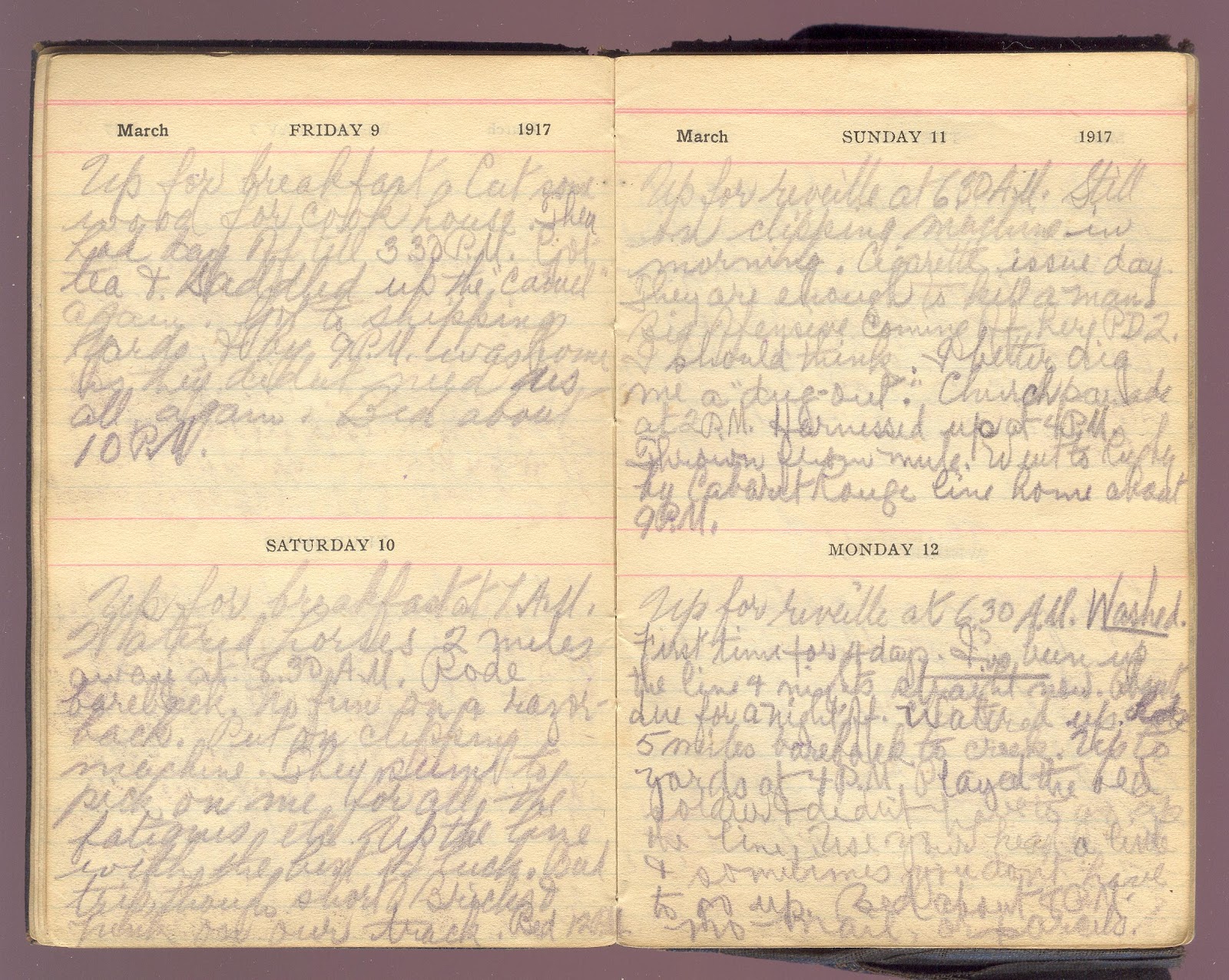

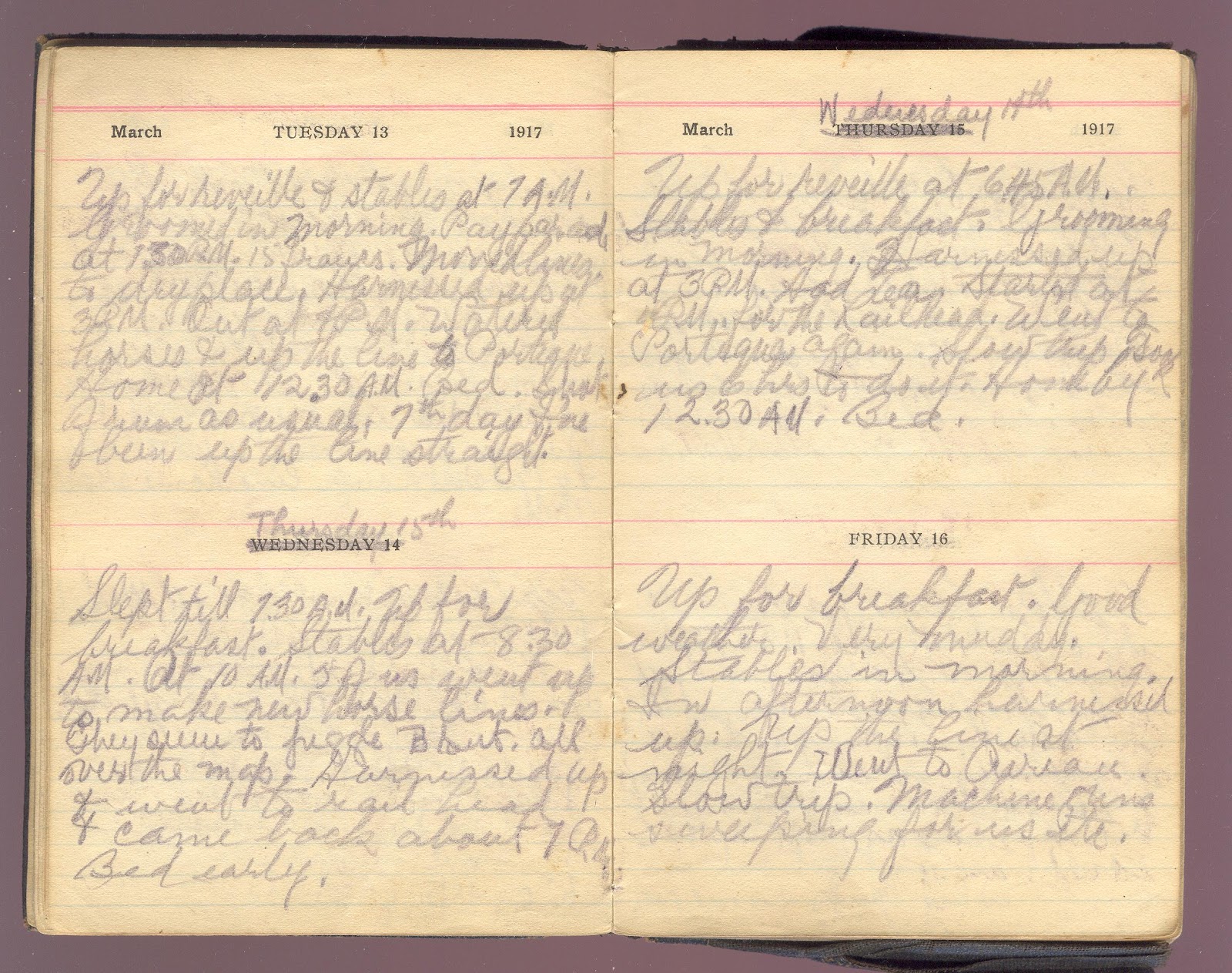

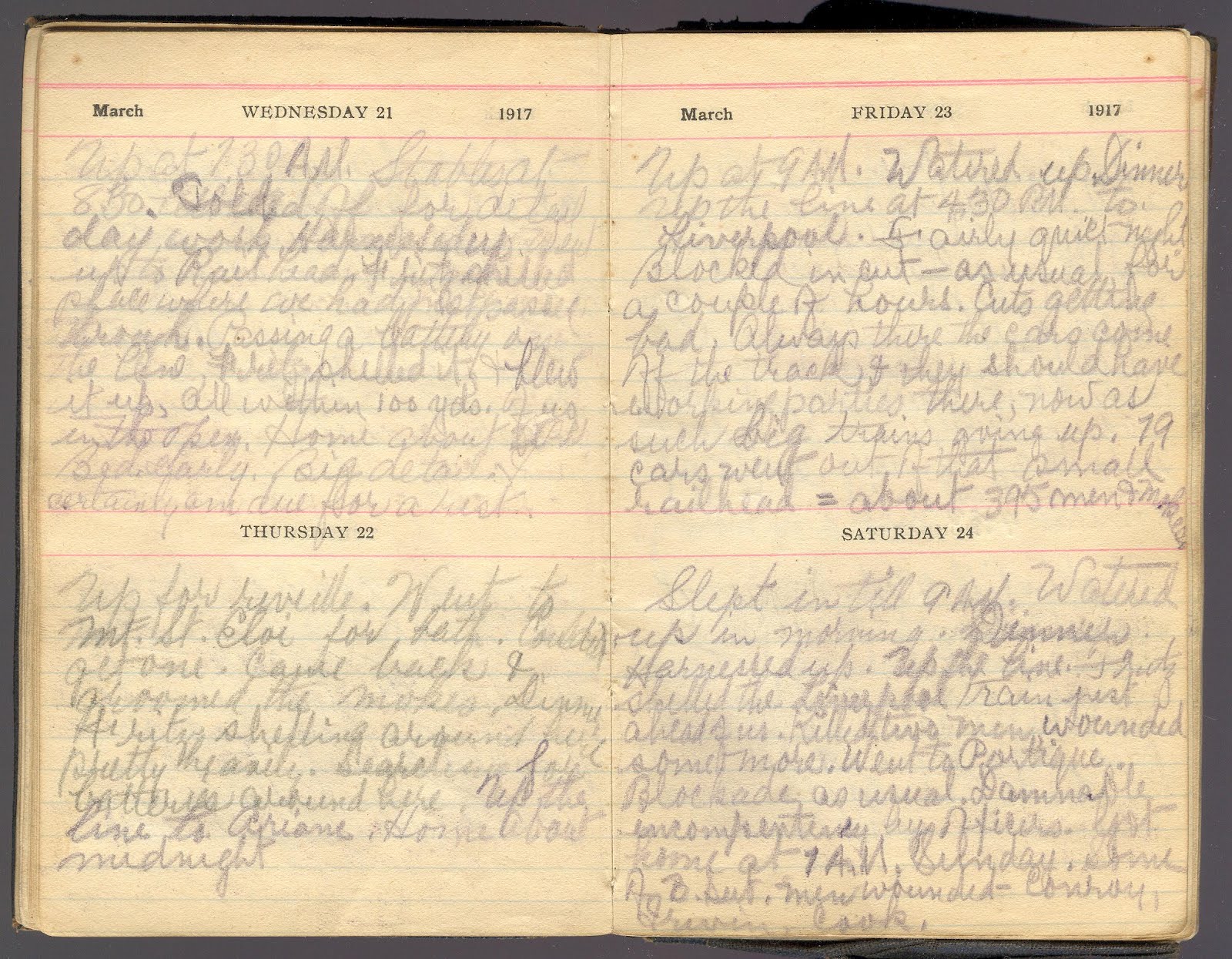

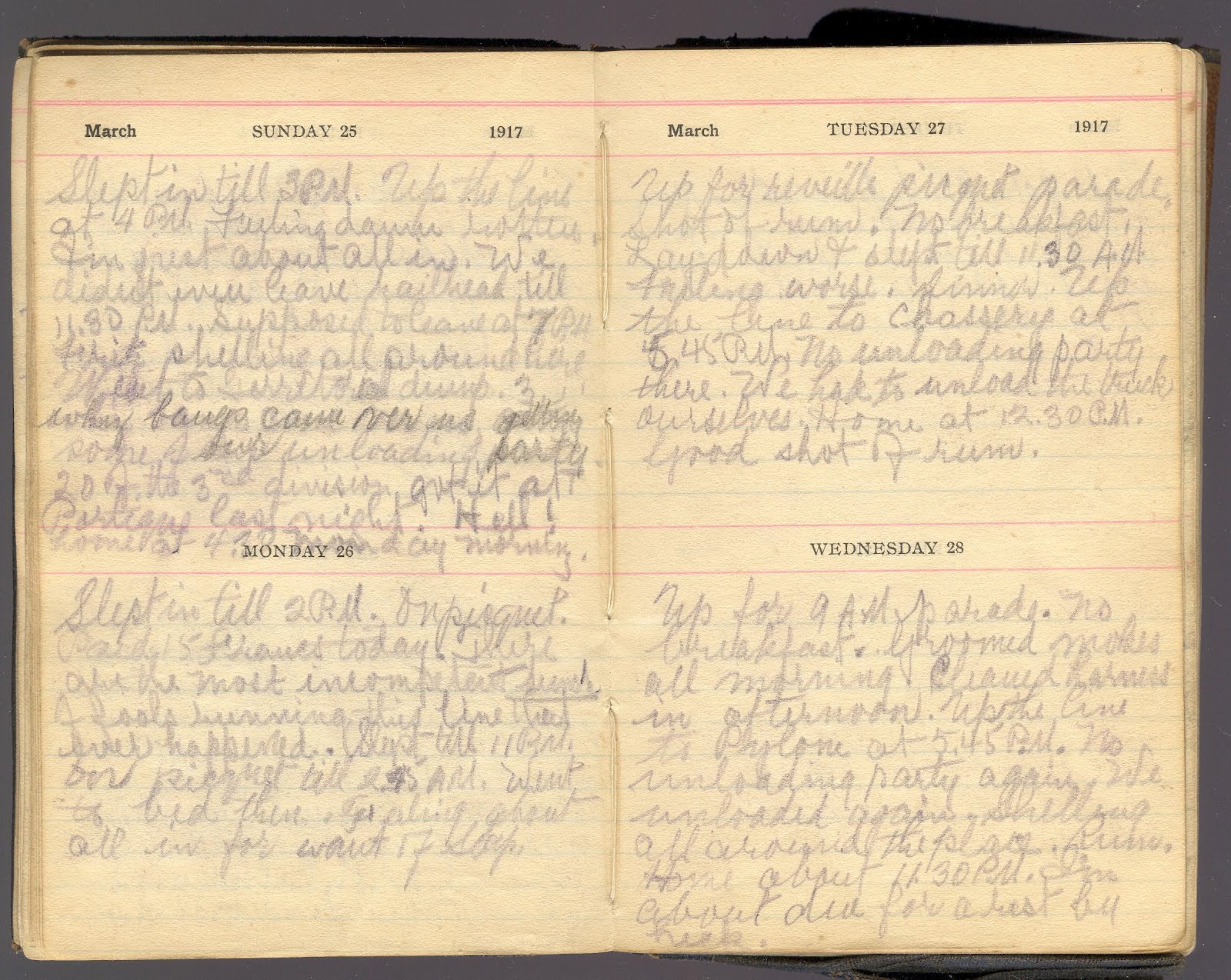

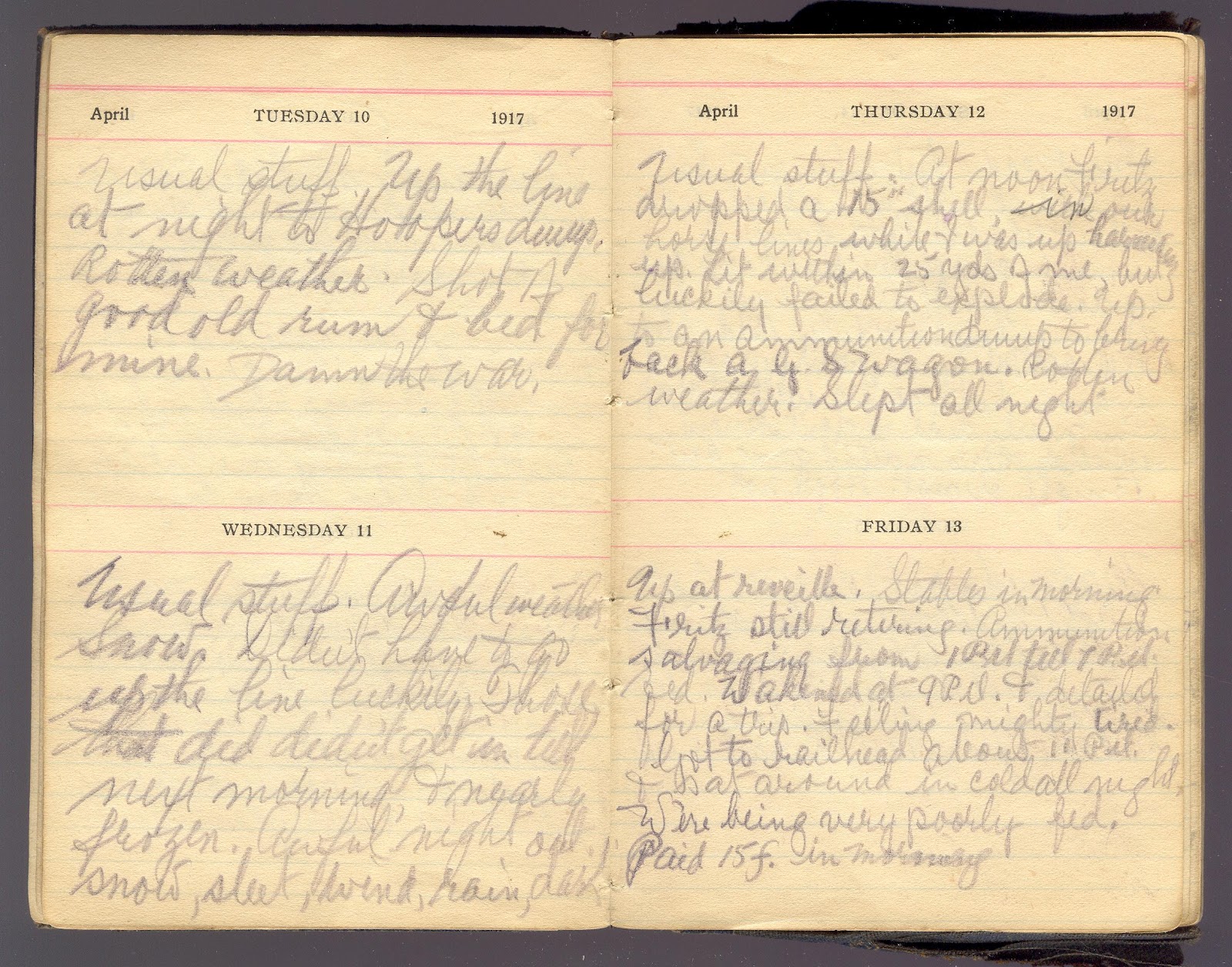

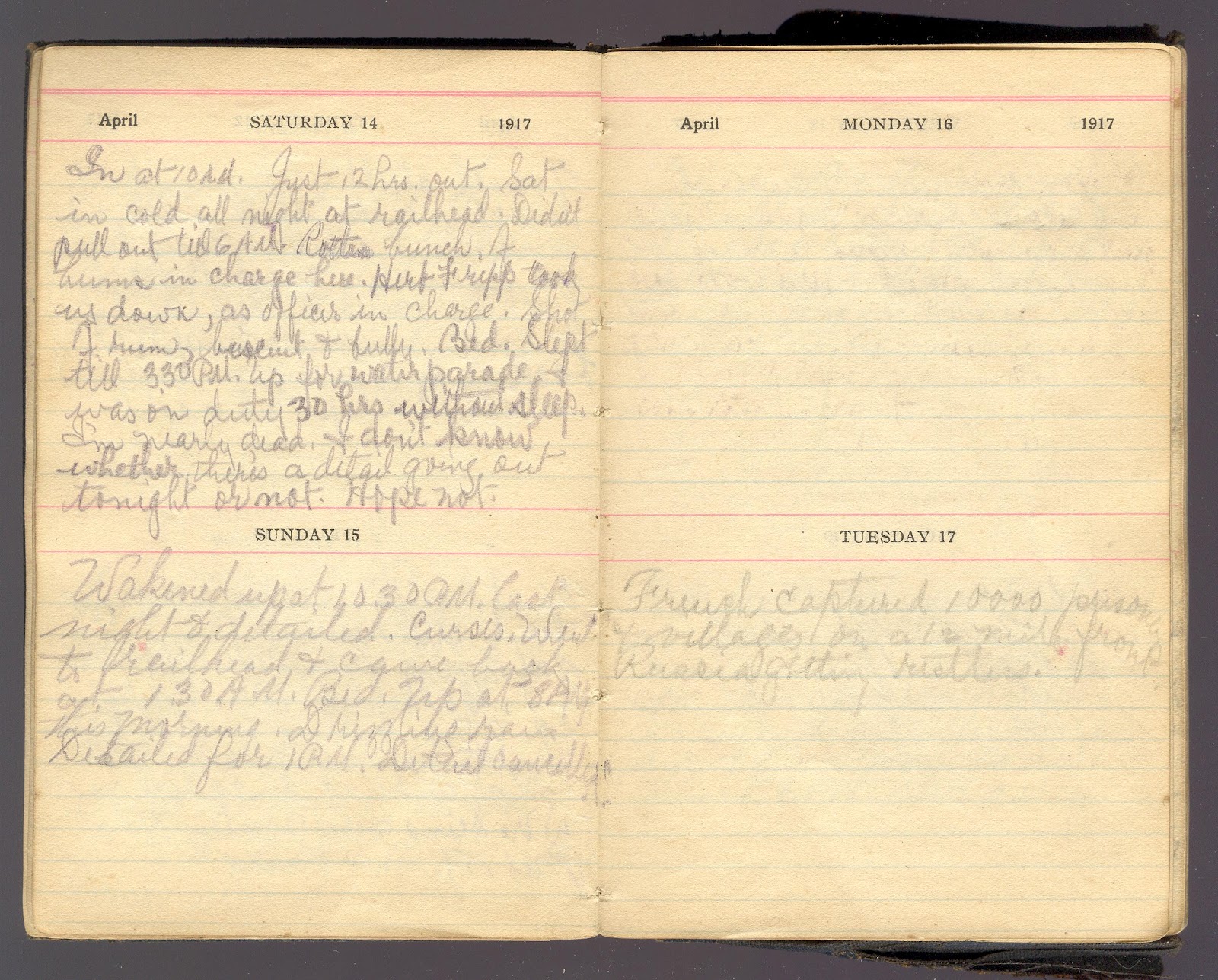

Reginald's diary entries from March and April 1917 provide an intimate window into one of the most defining moments in Canadian military history—the Battle of Vimy Ridge. In the weeks leading up to the assault, the Canadian artillery fired over one million shells, the largest artillery barrage in history to that point. The very earth trembled under the weight of this preparation, and men like Reginald worked tirelessly to ensure the guns never fell silent.

As a mule skinner, Reginald operated in what soldiers grimly called the "Devil's Zone"—the treacherous expanse between the front lines and the artillery positions where German counter-battery fire was most intense. His diary speaks of navigating by starlight and memory during blackout conditions, of paths that changed overnight under the relentless bombardment, of the constant awareness that each step could be his last.

The Battle of Vimy Ridge required an enormous logistical effort, with over 45,000 tons of ammunition moved into position in the weeks before the assault. Mule teams like Reginald's were essential to this effort, working in 18-hour shifts through mud that often reached knee-deep. The psychological toll was immense, as these men faced constant danger without the catharsis of combat, their trauma manifesting in what was then called "shell shock" but what we now recognize as PTSD.

Each mule in Reginald's team carried 4-6 eighteen-pound shells, weighing approximately 72 pounds in total. The paths they navigated were often little more than muddy tracks pockmarked with shell craters, some deep enough to swallow a man and his mule whole. A single misstep could detonate the volatile ammunition, ending not only the handler's life but those of his comrades as well. Yet night after night, they pressed on, driven by duty and the knowledge that the infantry depended on their courage.

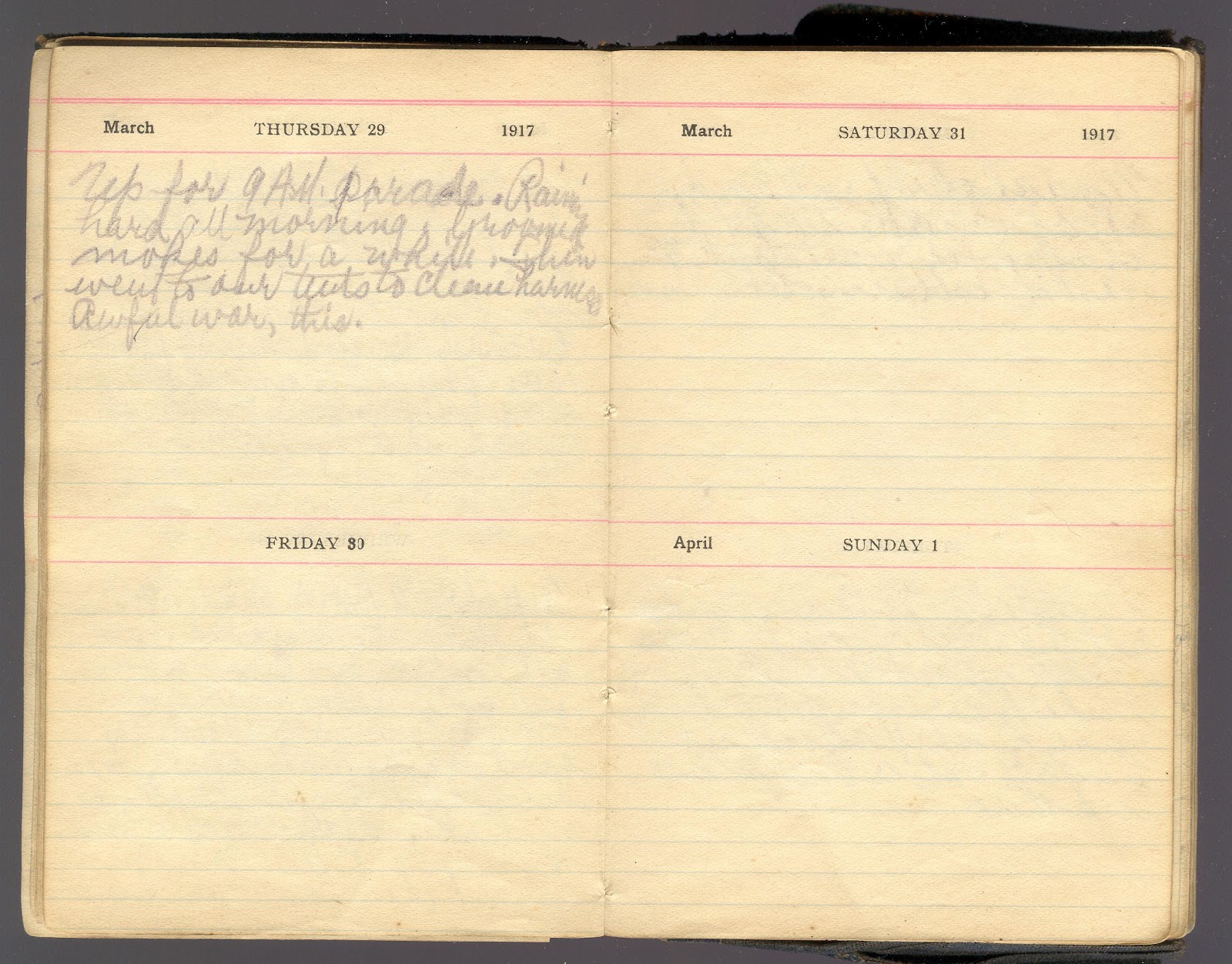

While the infantry prepared for the assault on Vimy Ridge, men like Reginald fought their own unseen battle against exhaustion, fear, and the brutal conditions of the Western Front. His diary entries speak of "boots rotting off our feet" and sleeping in "puddles of icy water" between shifts. Yet through it all, a remarkable resilience emerges—a testament to the human spirit's capacity to endure even the most unimaginable hardships.

The Invisible Wounds of War

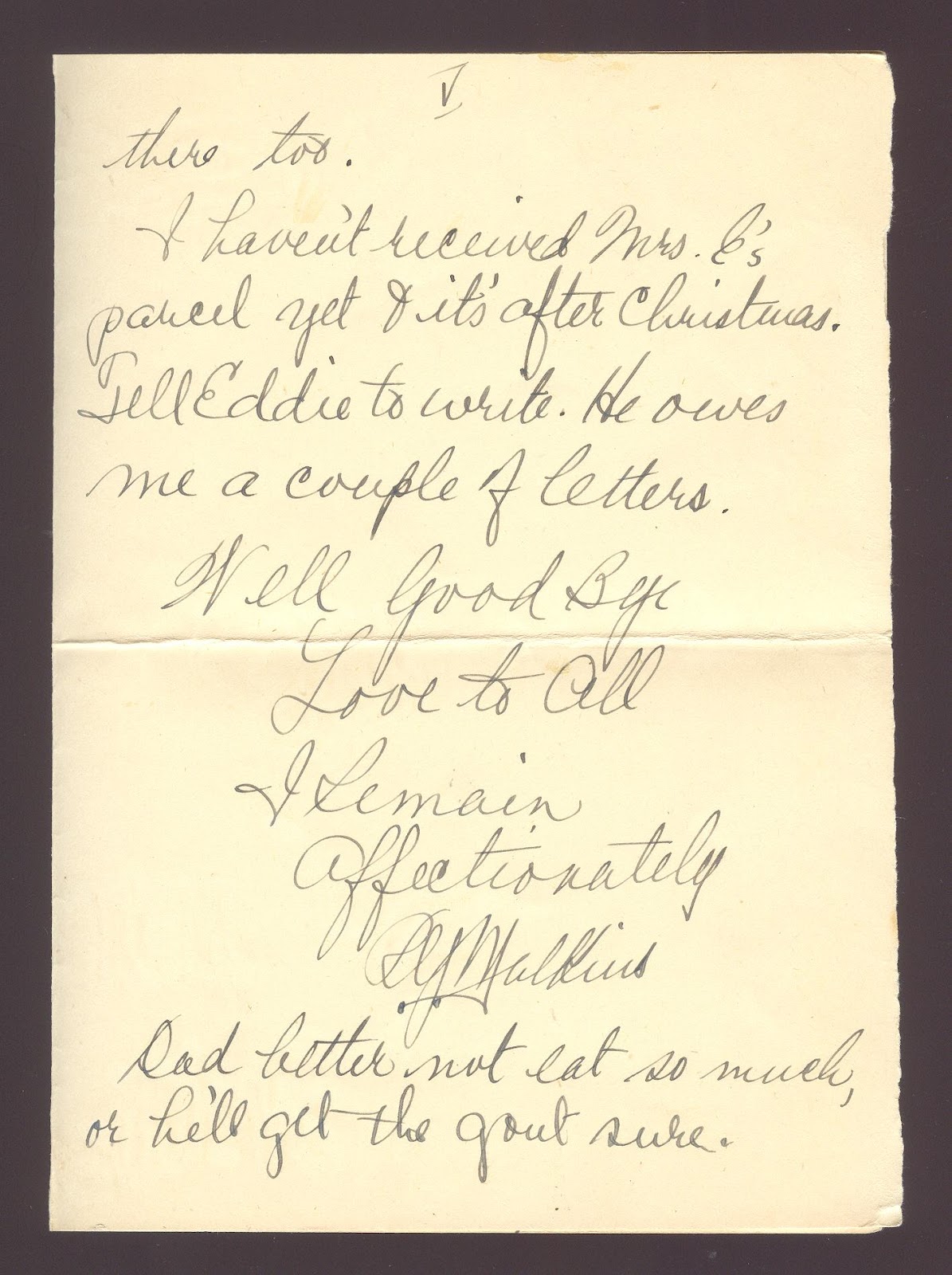

Like so many who returned from the Great War, Reginald Mulkins carried invisible wounds that would never fully heal. His diary reveals what contemporary doctors termed "war neurosis"—symptoms we now recognize as PTSD: nightmares that would jolt him awake decades later, a hypervigilance that made him startle at sudden noises, an emotional detachment that created a barrier between himself and those who loved him.

These invisible wounds were perhaps the cruelest legacy of the war. While a missing limb or a visible scar commanded sympathy and understanding, the psychological trauma remained hidden, a private hell that veterans endured in silence. Reginald's post-war medical records show treatment for what was then called "soldier's heart"—a poetic but inadequate term for the profound psychological impact of his experiences.

Life After the Silence

When Reginald returned to Canada in 1919, he faced a challenge perhaps as daunting as the trenches he had left behind: the challenge of reintegrating into a world that had moved on without him. His diary speaks of "the strange silence of peace" and the difficulty of connecting with family who could not comprehend the chasm between their experiences and his.

Like many veterans, Reginald found solace in the company of those who understood—the men with whom he had shared the crucible of war. He became active in the Great War Veterans' Association, the precursor to the Royal Canadian Legion, finding in these gatherings a space where his experiences needed no explanation, where the unspoken bond of shared sacrifice formed a bridge across the chasm that separated him from civilian life.

In 1923, Reginald married and raised three children, rarely speaking of the war until his later years. Like so many of his generation, he carried his memories in silence, protecting his loved ones from the horrors he had witnessed. It was only in the quiet of his final years that the full weight of his experiences began to emerge, as if the passage of time had finally granted him permission to unburden himself of the memories he had carried for so long.

Preserving a Family Legacy

- Complete Digital Archive: The full collection of Reginald's diaries, letters, and photographs preserved in our family digital archive

- Military Service Records: Reginald's complete service file available through Library and Archives Canada

- Historical Context: The Canadian War Museum's Vimy Ridge collection provides essential background for understanding Reginald's experiences

- Family Publication: "Mules, Mud, and Memory: The Great War Journey of Reginald Mulkins" (Family publication, 2010)

Reginald Mulkins passed away in 1962, but his legacy lives on through these pages. As his great-grandchild, preserving this history is not merely an act of remembrance but a recognition that history is not solely the domain of generals and statesmen. It is also the story of ordinary people like Reginald, who faced extraordinary circumstances with quiet courage, whose sacrifices formed the foundation upon which our present is built.

These diary pages are more than historical documents; they are a bridge across time, connecting us to a young man who, in the crucible of war, discovered the depths of his own resilience. In preserving his words, we honor not just his memory, but the memory of all those whose stories remain untold, whose sacrifices shaped the world we inhabit today.

The Diary Pages: March-April 1917

Click any image to view in detail