Bicycle Repair in Toronto

Jan 14, 2026A methodical practice, first learned with greasy hands on steel frames, now applied to clean abstractions in cloud architecture. This is a story about two kinds of tools, and the single mind that uses them.

My journey into professional bicycle mechanics began at Bike Pirates, a non-profit co-op in Toronto’s west end, where I learned the fundamentals. From there, I transitioned to Urbane Cyclist, a worker co-operative that profoundly shaped my approach to technical work. Urbane was more than just a shop; it was a hub for Toronto’s cycling scene, a community held together by shared values and, often, shared roti meals from Gandhi’s during staff meetings and parties.

It had a clear philosophy: serving the city’s daily riders, commuters, couriers, and cargo haulers, rather than chasing industry trends. This was a place that valued durable, practical bicycles built for the rigors of city life. The shop was founded by Eugene Yao, a Chinese-Canadian activist who was born in Shanghai in 1946 and came to Canada in 1969. He studied electrical engineering at McGill University, where he met his wife Winnie Ng. Eugene was later president of the Chinese Canadian National Council and was known for his generosity and kindness. He passed away in 2008, shortly after I joined the shop, but his commitment to quality and service continued to influence the shop’s culture. This ethos, rooted in quality and service, and instilled by Eugene, created a culture of meticulous attention to detail that I carried with me, first to Cycle Solutions for a deeper dive into performance bikes, and later into my career in technology.

An eviction notice in the summer of 2015, amid Toronto’s rising rents, prompted a move to Ottawa. This physical relocation coincided with a professional transition, from turning wrenches to writing code, from diagnosing drivetrains to architecting data pipelines.

The First Lesson: Assembly as Foundation

My first shift at Urbane Cyclist began with a test. The head mechanic asked me to assemble a bicycle from a box. After completing the task, his review was succinct: “I’ve seen a lot worse.” I was hired, and my real education began.

Urbane Cyclist at John and Queen. More than a shop, it was a cornerstone of the city’s cycling community and a second home for many of us.

Early days at the repair stand. I was just learning the ropes but already felt part of something bigger.

Assembly was the primary curriculum, and it demanded extreme diligence. A new bicycle in a box is not a finished product; it is a collection of parts with latent issues. Frames could be misaligned. Bottom brackets were often ungreased. Every bolt needed anti-seize to survive Toronto’s salted winters. The work required total presence. Is the brake housing compressed? Are the inline adjusters dialed in? Does the lever feel clean, not muddy, when squeezed?

The head of assemblies would inspect my work and point to a patch of dust on the frame. “Why is there dust on that bike?” Attention to detail was not aspirational; it was the baseline. This was my introduction to a core principle I would later seek in code: a clean foundation is non-negotiable. A misaligned derailleur hanger or a poorly torqued stem bolt would inevitably lead to a callback, just as a sloppy database schema or a misconfigured service mesh would cause a production incident. The feedback loop was just faster and more personal.

To the uninitiated, building a bike from a box sounds like attaching wheels and handlebars. In reality, it is a precise, multi-step process of system integration. A professional mechanic checks frame alignment, installs the bottom bracket and cranks, trues wheels, adjusts hub bearings, installs and tunes brakes and derailleurs, and more. Every component, from the headset to the drivetrain, must be installed, aligned, and calibrated correctly. For those curious about the full scope, this New Bike Assembly guide from Park Tool provides a comprehensive overview. It is the meticulous orchestration of mechanics, physics, and ergonomics into a single, reliable machine.

Deepening the Craft: From Following Instructions to Solving Problems

At Urbane, I built my own Urbanite touring bike from the frame up, including the wheels. It was a practical application of theory and taught me a hard lesson: even with premium components, a frame that is slightly too small will never be right. The bike later suffered two fork failures, blunt lessons in stress and material limits. This was my first encounter with a truth that haunts all system design: you cannot optimize your way out of a fundamental architectural flaw.

My custom-built Urbanite touring bike. A frame-up project that taught me as much about my preferences as it did about bike assembly. The first fork failure, a harsh but memorable lesson in material limits and real-world forces.

To expand my skills into mountain and performance road systems, I moved to Cycle Solutions. It was a smaller shop, which meant higher expectations. I took on customer intake, assessments, and scheduling. On some weekends, I was the only mechanic on duty.

That responsibility was both daunting and energizing. If a complex or unusual repair came through the door, it was mine to solve. Confidence grew with every wheel built and every persistent problem resolved. At Cycle Solutions, I truly felt seasoned, dealing with the kinds of failures no manual prepares you for. This was the transition from technician to engineer—from executing known procedures to diagnosing unknown failures and designing novel solutions. The “cheap repair” versus “proper repair” conversation with a customer was a lesson in systems thinking and trade-offs, not unlike choosing between a quick script fix or a refactored microservice.

Cycle Solutions on Parliament Street. This is where I stepped into a leadership role and handled the hardest repairs.

Wheel building is meditative: dozens of small, precise adjustments forming something straight and balanced.

Working on a single component. Total focus, everything else fades out.

Organized chaos. Every tool has a place, ready for the next problem.

A catastrophic hub failure. The kind of repair you secretly hope for when you are the only mechanic on duty—a pure, unambiguous problem.

The Work and the People: A Systems View of the City

We were a community. That included social events like this late-night bike race on a skating rink.

Working as a mechanic in Toronto meant serving a cross-section of the city: all-weather commuters, weekend riders with complex setups, students with resilient, improvised bikes. The shop was a node in a larger urban system. We weren’t just fixing bikes; we were maintaining a piece of the city’s transportation infrastructure. The salt, potholes, and construction dust that coated each bike were data points about Toronto’s environment. A bent rim told a story about streetcar tracks; a seized seatpost spoke of winter neglect.

This taught me to see the user behind the machine. In data engineering, the “user” can be an abstract consumer of an API or a dashboard. In the shop, the user was in front of you, explaining the weird noise, their commute, their budget, their fear of being late. This human context is what turns a technical specification into a meaningful solution. It’s the difference between deploying a generic data platform and architecting one that actually serves the needs of the analysts and scientists who will use it.

The city was our workshop. Its infrastructure shaped the bikes we repaired.

The daily reality. This is who we worked for: the cyclists of Toronto.

Salt, potholes, and constant construction. All of it showed up in the repair queue.

More than a job, it was a scene. The parties mattered as much as the work—they sustained the community.

An ever-changing skyline and rising costs. The pressures that eventually pushed me toward a new career.

The Translation: From Physical Systems to Digital Ones

I left bicycle repair in 2015 to study statistics and become a data engineer. At the time, with greasy hands and a sore back, I wanted a cleaner job, better pay, and a clearer path forward. I have that now. Still, I miss the tangible satisfaction of the workshop.

The core process is identical: listen, diagnose, choose the right tools, apply a systematic solution, and verify the result. The patience required to true a wheel—making dozens of tiny, opposing adjustments to find perfect balance—is the same patience needed to debug a distributed data pipeline where the fault could be in the networking, the code, the orchestration, or the data itself.

The profound difference is in the feedback. No one thanks you for a perfectly configured Kubernetes cluster the way they thank you for a silent, smooth-shifting drivetrain. The joy in tech is more internal, the satisfaction of a complex system humming silently, of an elegant solution to a gnarly problem. I traded an immediate, physical community for a stable, digital one; the visceral satisfaction of a trued wheel for the intellectual satisfaction of a passing integration test. This was not a change in values, but a translation of principles into a new domain.

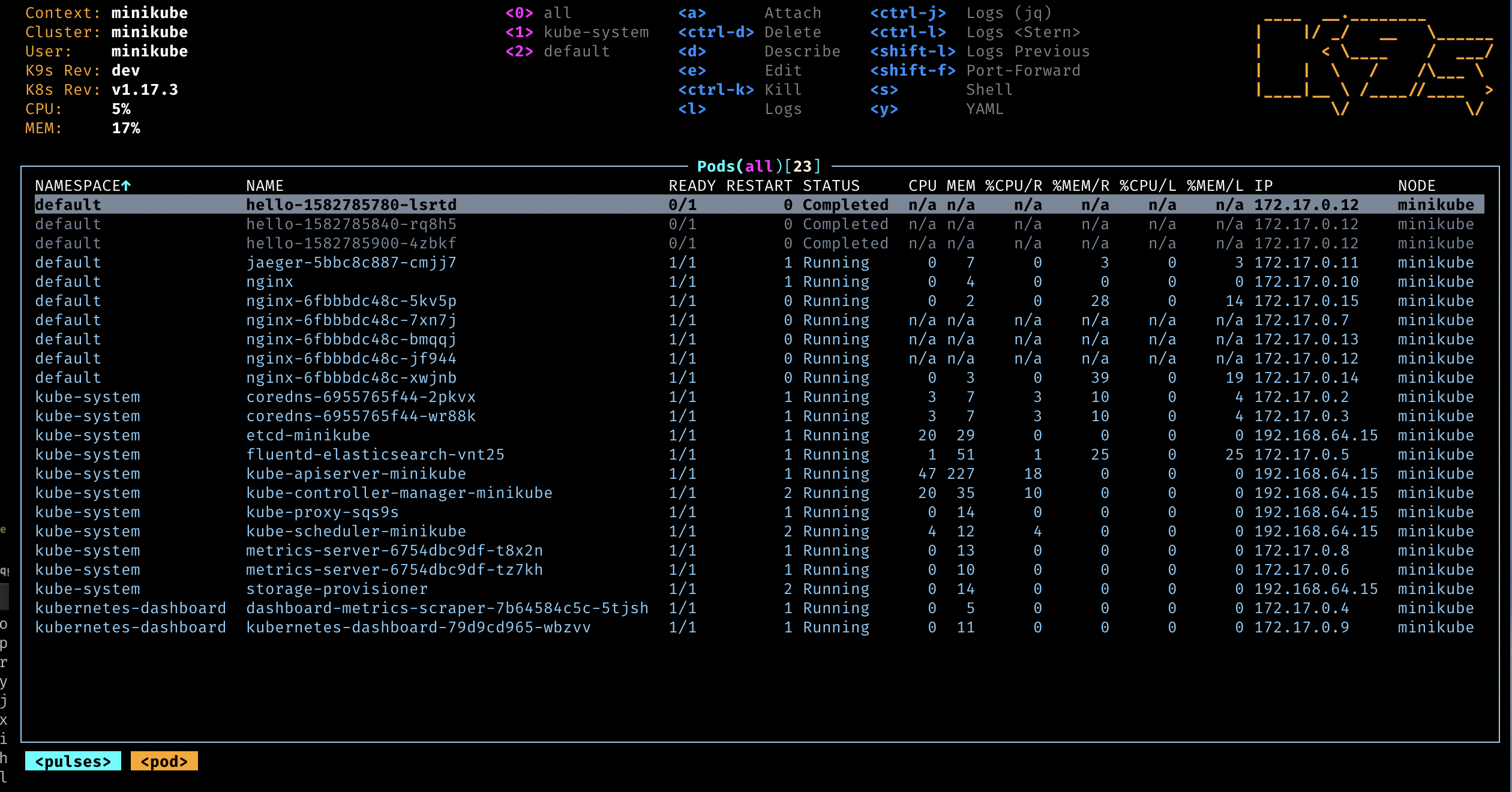

My Master’s in Statistics provided a theoretical foundation, but it didn’t prepare me for the hands-on reality of cloud infrastructure. To bridge that gap, I pursued the Certified Kubernetes Application Developer (CKAD) certification. This was a different kind of learning, one that echoed the practical, problem-solving nature of bike repair. The certification isn’t about theory; it’s a performance-based exam where you must design, build, and troubleshoot applications directly on the command line in a live Kubernetes environment. It covers everything from application design and deployment to networking and security. For those curious about what this modern form of digital craftsmanship involves, the Linux Foundation’s overview of the CKAD provides a detailed look into the required competencies. Studying for it felt like learning a new repair manual for a radically different kind of machine.

The new toolkit. YAML instead of spoke wrenches, but the same goal: a reliable, well-adjusted system. K9s. Abstract systems, same goal: reliability.

One area where the two worlds conceptually merge is public bike sharing. In places with ubiquitous systems, there’s a clear opportunity to apply data engineering and science, informed by cycling experience, to optimize operations. It’s a problem space where understanding the machine, the infrastructure, and the user is critical—a perfect confluence of my old craft and my new one.

My Bikes: A Personal History in Frames

Here are the bicycles I have owned as an adult. They are more than transportation; they are chapters.

2013 Giant Seek 3

Purchased at Cycle Solutions for its fit and durability. After assembling hundreds of bikes, its practical design and correct geometry sold me immediately. It remains reliable and enjoyable to ride. The aluminum frame accelerates well, and the geometry is comfortable, quick, and stable.

The high-visibility yellow fork likely makes it more noticeable to motorists and less appealing to thieves. The wide tires handle potholes well.

My trusty Ortlieb panniers, acquired secondhand from a fellow mechanic at Urbane back in 2009, are now 16 years old and still in daily use. Though the buckles have long given out and been replaced countless times, they continue to serve faithfully, albeit now more like indestructible buckets. I sold my Urbanite once I bought this bike since I prefer to maintain only one primary commuter. It is a lesson in choosing the right tool for the job and then maintaining it relentlessly.

2013 Giant Seek 3, my primary commuter. A lesson in the virtue of simple, correct design.

2013 Salsa El Mariachi 3

Bought from Urbane around the time I was leaving, but saw limited use. I rode it in the Don Valley a few times, but Toronto’s frequent rain makes conditions unreliable for singletrack. Sometimes, you acquire a tool for a version of yourself you aspire to be, or a life you imagine living. This bike represents that potential—beautiful, capable, but waiting for the right context.

2013 Salsa El Mariachi 3. A tool for a different terrain, both literal and metaphorical.

2009 Urbanite Touring

My custom Urbanite touring bike. I used this for commuting in Toronto for six years and completed several 100km+ rides on it. I sold it before moving to Ottawa. I loved this bike and rebuilt it multiple times, but fundamentally, it was the wrong size. It was my most profound teacher: no amount of love, care, or premium components can overcome a foundational mistake in specification. It is the bike that most directly informed my approach to system architecture.

The Urbanite before sale. A beautiful machine built on a flawed premise.

2008 Fuji Track

This bike was a lot of fun. I bought it in Toronto from Bikes on Wheels in Kensington Market and took it to the UK in a box. It took one day to adapt to left-side traffic. This bike fit me perfectly, which was a nice change from the KHS. I later sold it to make room for my Urbanite. The bars were nice and wide. It was pure, simple, direct. In tech terms, it was a minimal, single-purpose application with an excellent user interface.

2008 Fuji Track. Elegant simplicity and perfect fit.

2006 KHS Flite 100

My first fixed-gear bike. It taught control on Vancouver’s hills, where momentum matters and coasting is not an option. I rode this bike without brakes for a few days but descending hills was a bit scary sometimes so I added a Tiagra front brake. I changed the stem and handlebars a few times on that bike. I never could get it to feel like a good fit. When I sold it, it had bull horn bars and a time trial brake lever.

The bike had a beautiful red finish but the paint chipped easily, and after a couple of years of riding as a commuter it was speckled with white chips everywhere as the undercoat was white. And the bike was too small. It was my first project, my first lesson in the limits of modification, and a reminder that aesthetics wear thin when fundamentals are off.

2006 KHS Flite 100 in Vancouver. The first love, full of lessons about form, function, and fit.

Bryan Paget worked as a bicycle mechanic in Toronto from 2009 to 2015, where he learned that all systems—whether made of steel, carbon, or code—require clean foundations, careful diagnosis, and an understanding of the human they serve. He is now a data engineer specializing in Kubernetes and data platform architecture, applying the same principles to a different kind of machine.